An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

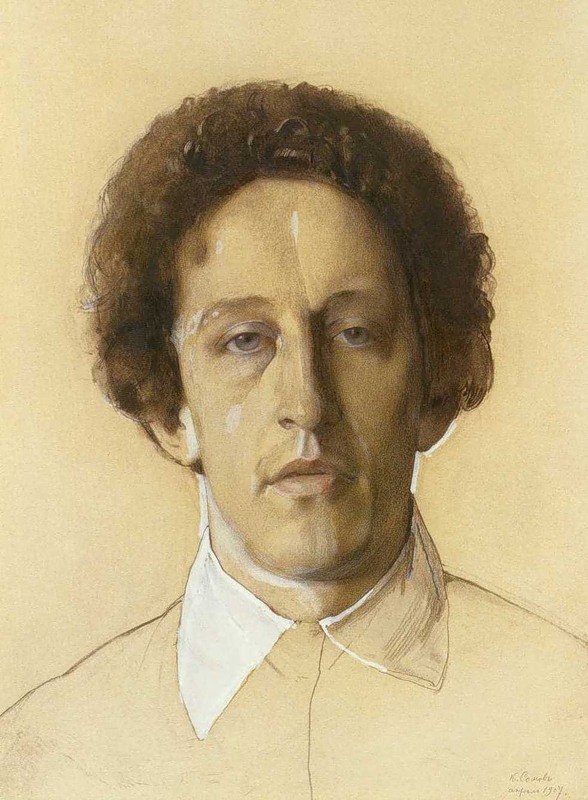

V. MAYAKOVSKY

Not so, comrade!

I hate the Winter Palace and the museums no less than you do. But destruction is as old as construction, and as traditional. Destroying something you no longer care for, you yawn and are as bored as when you watched its construction. History’s fang is more venomous than you think, you cannot escape the curse of time. Your cry is still a cry of pain, not joy [Blok added a note: “Wagner”]. Destroying, we are the same slaves of the old world; a breach with traditions is a tradition. There is a greater curse upon us: we cannot help but sleep, we cannot help but eat. Some build, others destroy, for ‘there is a time for everything under the sun,’ and all will be slaves until a third thing appears, equally dissimilar to construction and destruction.

• • •

В. МАЯКОВСКОМУ

Не так, товарищ!

Не меньше, чем вы, ненавижу Зимний дворец и музеи. Но разрушение так же старо, как строительство, и так же традиционно, как оно. Разрушая постылое, мы так же скучаем и зеваем, как тогда, когда смотрели на его постройку. Зуб истории гораздо ядовитее, чем вы думаете, проклятия времени не избыть. Ваш крик – все еще только крик боли, а не радости [Прим. А. Блока: “Вагнер“]. Разрушая, мы все те же еще рабы старого мира: нарушение традиций – та же традиция. Над нами – большее проклятье: мы не можем не спать, мы не можем не есть. Одни будут строить, другие разрушать, ибо “всему свое время под солнцем”, но все будут рабами, пока не явится третье, равно не похожее на строительство и на разрушение.

☛ Alexander Blok, Собрание сочинений, (Collected Work) in 8 volumes, ed. C.N. Orlova, A. A. Surkova, and K.I Chukovsky, State Publishing House, Moscow – Leningrad, 1963, Volume 7, p. 350 (PDF). English translation based on William Todd III’s translation included in the essay “The Poets and the Revolution — Blok, Mayakovsky, Esenin” by George Annenkov (The Russian Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, April, 1967, pp. 134-135). The same excerpt can also be found on the Russian version of Wikisource, as well as on Blok.lit-info.ru, a website dedicated to the work of Alexander Blok.

As indicated, Blok’s note is partially reproduced and discussed in George Annenkov’s essay. The English translation by William Todd III was based on excerpts available in Volume 1 of Annenkov’s memoirs originally published in 1966 under the title Дневник моих встреч : Цикл трагедий (Dnevnik moikh vstrech. Tsykl tragedii – A Journal of My Meetings: Cycle of Tragedies). In a 2005 reedition available on Internet Archive, the relevant excerpt can be found on p. 74 (PDF) (an account is required to borrow the book). In an older reedition from 1991 (Дневник моих встреч : Цикл трагедий. Том 1), the same excerpt can be found on p. 73.

In volume 7 of Собрание сочинений, (Collected Work) from 1963, footnote no. 82 provides additional context for Blok’s draft note to Vladimir Mayakovsky (pp. 510-511; PDF). The note was meant as a draft response to the poem “It’s Too Early to Rejoice” by Mayakovsky, published on the front page of the newspaper Искусство коммуны (Art of the Commune), Issue 2, December 15, 1918, p. 1 (PDF; English translation by James H. McGavran III, in Vladimir Mayakovsky. Selected Poems, Northwestern University Press, 2013, pp. 74-75: PDF). The note itself is mentioned in Blok’s Notebooks, collected in a volume from the same Collected Work series (an extra, unnumbered volume, in addition to the 8 numbered volumes, published in 1965). The entry is dated from December 30, 1918, and can be found on page 442 (PDF), where one can read Blok’s principle: “нарушение традиции есть тоже традиция” (“breach of tradition is also tradition”).

In Selected Poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky, where “It’s Too Early to Rejoice” is reproduced, English translator James H. McGavran III explains:

This poem represents the high point of Mayakovsky’s “out with the old, in with the new” stance vis-à-vis the classics of art and literature—a feigned or at least exaggerated cultural illiteracy for which the Futurists were notorious—but it still feels more like a pose than a stance. Mayakovsky developed a far more comradely attitude toward his forebears in the 1920s. The strident military idiom of “An Order to the Army of Art” is here taken to an extreme—the front-page forum in Art of the Commune seems to have brought out the ringleader in Mayakovsky. (Northwestern University Press, 2013, p. 341)

• • •

My thanks to Prof. Vladimir Golstein for his helpful assistance in locating Blok’s draft in 8-volume Collected Work edition. I first came across Blok’s note in an excerpt from Dionys Mascolo’s unpublished notebooks (Carnets) (see Lignes, no. 33, March 1998, p. 203; link, PDF, PNG). The same part of Blok’s note noted by Mascolo is used to conclude the presentation («Précisions») of the collected volume Appel. Et autres textes suivis d’effets (édition Divergences, 2023, p. 13; JPG). A partial French translation of Blok’s note is offered by Renée Poznanski in her book Intelligentsia et Révolution : Blok, Gorki et Maïakovski face à 1917:

«Pas ainsi, Camarades! Je ne déteste pas moins que vous le Palais d’Hiver, et les musées! Mais la destruction est un phénomène aussi ancien que la construction, et aussi traditionnel. (…) En détruisant, nous restons les mêmes esclaves de l’ancien monde: contrevenir aux traditions, c’est également une tradition». (Éditions Anthropos, Paris, 1981, p. 192)

• • •

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art

- Tagged: Blok, construction, destruction, Mayakovsky, New, old, poetry, tradition