An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Ragnar Axelsson: From the series Greenland, a sled dog in a blizzard, Ittoqortoormit, Greenland. First published in Faces of the North (originally Andlit Norðursins, Reykjavík: Mál og menning, 2004). Republished in Last days of the Arctic (originally Veiðimenn norðursins, Reykjavík: Crymogea, 2010). © Ragnar Axelsson. Used with permission.

The above photo was shot in the small town of Ittoqortoormit (sometimes spelled Illoqqortoormiut), the only permanent settlement in the region of Scoresby Sund. This geographical region is a fjord system on the East coast of Greenland and is said to be the largest fjord system in the world (see Archaeology and Environment in the Scoresby Sund Fjord, p. 7). In 2012, the total population of Ittoqqortoormiit was 477 habitants (see Statistics Greenland: “Population in towns and settlements July 1.st”). The town is located on the 70th parallel north. As a mean of comparison, the Arctic Circle begins at the 66th parallel north (see Wikipedia). The farthest north I have ever lived was on the 55th parallel.

Ragnar Axelsson has said of this dog: “He stood up, shook the snow off, then lay down and let the snow cover him again.” (LENS: “Showcase: Black and Very White” December 7, 2009; photo no. 9). In an email exchange with him, I asked about the context in which this photograph was taken. He provided the following, additional details (I added the link):

The photograph was taken in a blizzard. The glacier storms in Greenland are called Piteraq and can be so strong that houses are sometimes blown away. It has not happened for many years.

• • •

Ragnar Axelsson, also known as RAX, is a renowned, award-winning freelance photographer born in Iceland in 1958. He has been documenting the vanishing lifestyles of various Arctic communities for the past 30 years. Here’s what he has to say about Greenland in particular:

Greenland, the biggest Island in the world, is a pearl with harsh elements. Inuites have been there for more than 4.000 years living on the land. In the old days Inuites where living in igloos and small cabins made of stones. It was a struggle for food everyday; hunting birds, fish, whales, seals, walruses and polar bears. Every single part of the hunted animal was being used. Skin for clothing, meat was eaten. The old hunting tradition is fading away as new posibilities in the modern world are taking over. (source: Fotopub.com)

Rax’s photos have been featured in publications such as LIFE, National Geographic, Le Figaro, Stern, La Vanguardia, TIME and The New York Times. He has held exhibitions in Iceland, France, Germany, Italy and the United-States (see his complete official profile). So far, he has published two books: Face of the north (originally Andlit Norðursins, 2004) and Last days of the Arctic (originally Veiðimenn norðursins, 2010). English versions for both those books appear to be sold out almost everywhere at the time of writing. Used copies, although available, are quite expensive (Shop Icelandic may still have some copies of Last days of the Arctic). Apparently, the publisher Forlagid is planning to release a new English edition of Faces of the North in 2013 (see Shop Icelandic for details).

Alternatively, there are other ways to enjoy RAX’s work. One of the best introduction available is the beautiful documentary film which bear the same title as his last book: The Last Days of Arctic by Magnús Vidar Sigurdsson (2011, IMDb). The film, produced by Sagafilm Productions and distributed by Mercury Media, won Best Documentary award at the Icelandic Film & Television Awards in 2012. The trailer is available both on Vimeo and YouTube. Watch it below:

The film seems to exist in two different versions: one 90-minutes version (see IMDb and Icelandic Films) and one 60-minutes version. The one-hour long version was first broadcast on BBC4 on May 2011 (the film was also dubbed in French and broadcast by ARTE on December 2011: a 15 minutes excerpt is available on YouTube: “Les Visages de l’Arctique”). Digital copies of the 60-mins version can be bought or rent through either iTunes US or Amazon Instant Video. The DVD seems to be available at some online location (see nammi.is and Shop Icelandic) and, if one is to believe the information available on those website, offers the “full feature 90 min documentary”.

In an interview he did with Arctic Portal on August 2011, Rax talked about what it was like to make this documentary and what it’s all about:

“The film succeeds the books. We travelled everywhere and met the people, but the weather was too good! I missed the storms I saw when some of the pictures were taken,” Rax told the Arctic Portal website. He stopped counting his trips to Greenland. “I think they might be around 25-27. That averages about one a year. It is very expansive to go to Greenland and sometimes I did not gain anything. Then I just had to go home and collect more money for the next trip.”

Born and raised near a glacier in Iceland, he has seen the effects of global warming, both at home and in his trips. “One can definitely see it when travelling to the same places, 5 or 10 years later. The landscape is constantly changing. I did not realize the effects at first, I just wanted to go and shoot beautiful photos. I wanted to go where nobody had gone, challenging the cold, the distances and the weather. So many photographers just want to sit around in Africa, naked in the sun,” he joked.

“I saw the effects of climate change when I started. Sometimes with my eyes, the ice had melted, and sometimes with help of the Greenlandic hunters. They are amazing. They know all about this. They can feel it, it is in their bones.” “You could ride in a dogsled around one area, but in the next trip the ice was too thin. Some areas became impassible.”

The film is called Last days of the Arctic, but is that really the case? Are the hunters life’s threatened by climate change? “Well, the film is a thought about this. The Arctic will change, including the lives of the people. Hunters rely on areas to fish and hunt, some of these areas will be impossible to reach when the ice is to thin,” Rax said. (Arctic Portal: “Last days of the Arctic: Documentary with Rax” August 17, 2011)

In a shorter video produced by the publisher Sagenhaftes Island (YouTube, uploaded on Jul 14, 2011 – 10m22s), Rax discusses the making of his last book. He talks about the men and women of the Arctic he has come to know during the various expeditions that have brought him in those northern regions for the past thirty years. In the following transcript, he clearly explains how climate changes is impacting the lifestyles of those communities (the complete video is embedded below):

In Greenland, I talked to hunters I’ve known for twenty years. It’s obvious that they’re worried about the future of hunting and themselves. They can see that in areas where they’d travel on dogsleds without a second thought, the ice is now too fragile. They can’t reach their hunting grounds because the ice is too thin. The hunting seasons becomes shorter. They also have boats, of course, and hunts for fish and other things, but their lives could change very rapidly if the ice vanishes. […] The problem is real. This is happening. But the world doesn’t seem to know much about this life, or respect the fact there is life there. People live there. And their lives will change. Of course they’ll find a way for themselves. But this culture, 4,000 or 4,500 years old, of surviving in these extreme conditions, it could change very quickly. I can’t envision the young people of Greenland making a living from hunting, or wanting to.

Another, simpler way to discover about Ragnar Axelsson is to browse through the various galleries available on his official website. One can even flip through a digital preview of his latest book The Last Days of Arctic. Here’s how the book is introduced on his website:

The world turns its gaze toward the Arctic. Nowhere are the signs of climate change more visible; here global warming already affects the day-to-day lives of the local people. Still the circumpolar Arctic is one of the most disputed territories on Earth, with many nations laying claim to the mining and oil rights of the area as the sea ice retreats. For thousands of years the Inuit have built their communities based upon a sensitive understanding of the land and the frozen ocean, but rapid social and environmental change threatens their traditional way of life. The hunters of the North are a dying breed. This is the twilight of their society.

Ragnar Axelsson has been travelling to the Arctic for almost three decades, drawn by a deep respect for the hunting communities of northern Greenland and Canada. His images have won him recognition as one of the most accomplished documentary photographers of our time. This remarkable body of work is finally brought together to present a unique record of the daily life and culture of some of the most remote communities in the world.

English publisher Polarworld also offers to browse a preview version of the book online (although at the time of writing, the book is out of stock on their website too). A video trailer of the book is available on YouTube as well. Watch it below:

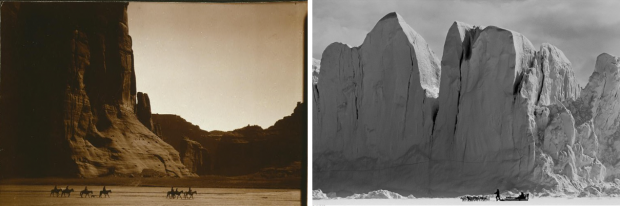

Finally, I’d like to draw attention to a particular photo of the Greenland series. The photo, taken from afar, shows two hunters travelling with their dog sled on the Inglefield Fjord. As they slide their way on the white floor, they are dwarfed by gigantic icebergs in the background. Those two figures –men and icebergs, extremely small and extremely big– are both threaten to disappear. In the world being photographed by Axelsson, the culture goes hand to hand with the landscape. Maybe it has always been the case, but it seems more obvious in this photography. One may think that the artificial structures we have become accustomed to –roads, buildings, bridges– have come to mask the importance of this relation.

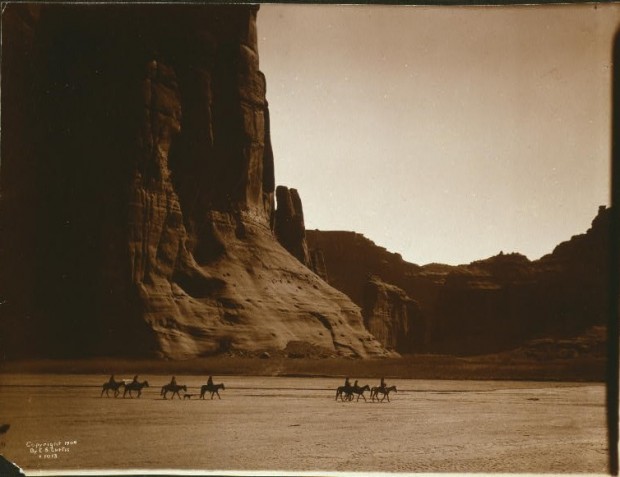

About a hundred years earlier, and 4,000 kilometers to the Southwest, another photographer was busy recording another vanishing culture. Edward S. Curtis extensively documented the life and culture of the Native American people at the turn the twentieth century. One of his most famous portrait was taken c. 1904 in Canyon de Chelly (Arizona, U.S.A.). It shows what is believed to be seven Navajo riders on horseback, riding their way on the floor of the canyon. In the background is the geological formation known as a sandstone spire: it rises 750 feet high into the air, well beyond the frame of the photo. This landscape was also changing at the time the photo was taken, maybe not the canyon itself, but everything around it. As those Native American were travelling, other men were busy erecting entire cities made of skyscrapers. Today, what was once familiar has become strange and what is artificial we experience as the most familiar. The photo by Edward S. Curtis was retrieved from The Library of Congress (LOT 12311).

• • •

To learn more about Ragnar Axelsson and his work, consider the following links:

-

Visit his official website. Crymogea is the Icelandic publisher of the book The Last Days of Arctic. Prints can be bought either through his website (“Prints for sale”) or at Proud.co.uk

-

Axelsson’s work was featured twice on The New York Times website: once in the “Travel” section (see “The Hunters of Greenland”) and once on its photoblog LENS (see “Showcase: Black and Very White” by Miki Meek, December 7, 2009). The Independent and The Telegraph also offers such slideshows.

-

Batterie Not Included: “Ragnar Axelsson’s Faces Of The North”, October 30, 2006. This interview considers the technical aspects of Axelsson’s work. Some links are broken (the blog where the interview is hosted doesn’t seem to be active anymore).

-

Photo JBartlett: “10 Questions with Editorial Photographer RAX” by Jeff Bartlett, May 23, 2011. This interview comes with very large reproduction of 12 photographs by Axelsson.

-

Photo Bards: “Ragnar Axelsson”, 2011. Another short interview (no author, undated except for the comments)

-

Beyond the Box: “Last Days of the Arctic, Sunday on Global Voices” by Annisa Kau, June 8, 2012. That’s actually a substantial interview with Margrét Jónasdóttir who is the producer of the documentary film Last Days of the Arctic (see above).

-

There are two more short videos about Ragnar Axelsson made by Jón Snær Ragnarsson. The first one simply titled RAX was made in 2007 (a copy is also available on YouTube). The second titled RAX, South Pole 2010 was made three years later during a trip to Antarctica.

• • •

Related: “Dog Chris, listening to the gramophone, Antarctica” by Herbert Ponting, c. 1911

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication, Photography

- Tagged: Arctic, book, cold, culture, dog, Edward S. Curtis, environment, Greenland, nature, Ragnar Axelsson, snow, winter