An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

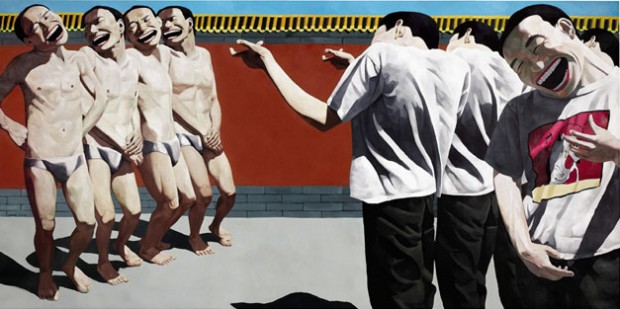

☛Initial Access: “Between Men and Animal” by Yue Minjun, oil on canvas, 280cm x 400cm, 2005

From Initial Access, the Frank Cohen collection:

Minjun’s toothy faces have been likened to the expansive smiles of fashion models or faces in a toothpaste commercial but, although they have their origins in advertising and are based upon a knowledge of western pop art, Yue Minjun draws upon the Christian iconography of the Renaissance as well as that of Chinese folklore. Rather than being a source of comfort, the smiles on Yue Minjun’s characters embody a sense of threat, their laughter is not an expression of happiness but mania, a psychosis that mocks the viewer and separates the subject from the norm. His painting Between Men and Animal depicts a crowd of identical laughing figures. From each of their heads sprout two little horns and they assume the personas of mythical demons. The title of the painting suggests a relationship between higher human nature and the baser condition of animals. (more)

From the Saatchi Gallery:

Immediately humorous and sympathetic, Yue Minjun’s paintings offer a light-hearted approach to philosophical enquiry and contemplation of existence. Drawing connotations to the disparate images of the Laughing Buddha and the inane gap toothed grin of Alfred E. Newman, Yue’s self-portraits have been describe by theorist Li Xianting as “a self-ironic response to the spiritual vacuum and folly of modern-day China.”

Yue Minjun has been associated with the “cynical realism” movement:

Like the artists of Political Pop, the Cynical Realists betray an ambiguous relationship to contemporary China. Their work neutralizes every political position, hovering in a kind of ideological suspension; they neither mock the politics of the Cultural Revolution, nor do they affirm their complicity with them. The political is not avoided, however; it is relentlessly engaged, but always from a cynical distance that affirms no particular stance. The result is a kind of stylized ambivalence, a form of humor (it does not even have the clear negativity of irony) that traverses the political field, establishing itself neither within nor outside it. (read more over at the Art and Culture website)

In a 2007 interview with CNN, Yue Minjun refused to be associated with this movement:

Yue said he does not agree with being tagged a “Cynical Realist,” a term coined by leading art critic Li Xianting to describe China’s post-Tiananmen generation of disillusioned artists. At the same time, he doesn’t concern himself about what people call him, he said. (“‘Execution’ artist rejects Tiananmen label” by Elizabeth Yuan, October 15, 2007)

Yue Minjun’s painting “The Execution” (oil painting, 150 cm × 300cm, 1995) became one of the most expensive Chinese artwork by a contemporary artist when it was sold in 2007 for about 5.9 millions US dollars at London’s Sotheby’s. The painting is reminiscent of Fransisco Goya’s “The Thirs May 1808” (1814) and has been read by some as a comment on the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. See the image below and learn more about it on Wikipedia.

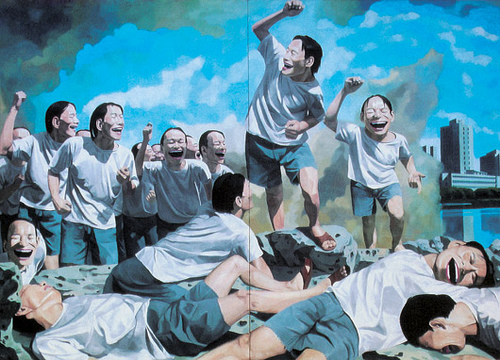

“The Massacre at Chios” (inspired by Eugène Delacroix’s “The Massacre at Chios”) and “La Liberte guidant le peuple” (inspired by Delacroix’s famous “Liberty Leading the People” painting) seem both to offer a similar comment on the way we relate to history while trying to cope with the present situation.

First, “The Massacre at Chios”, oil on canvas, 250cm x 364cm, 1994 (more info, image source: Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty Images):

Second, “Freedom Leading the People”, oil on canvas, 360cm x 250cm, 1996 (image source):

What strikes at first with the above paintings is the repetition of those smiling figures (apparently, all those faces are auto-portrait of the artist), all frozen in what looks like a euphoric expression. In a sense, those paintings (as well as many others by Yue Minjun) convey a sense of indifference (of in-differentiation). There doesn’t seem to be a difference ―be it physical or psychological― between all those characters. They all look the same, indifferent to the historical and political context of the scene where they stand.

Here are some more resources about Yue Minjun:

- Yue Minjun page over at the Art Speak China website, “a bilingual, online resource devoted to contemporary Chinese art” (which is itself a very interesting resource). A rich article with plenty of external references. Images of Minjun artworks are lo-res.

- Yue Minjun’s official website (bilingual). Its gallery uses lo-res images of artworks, but provides accurate details (year of production, medium, dimension). The site also offers a well developed biography along with a list of 13 reviews and interviews.

- Yue Minjun’s page over at the Saatchi Gallery

- A 2007 review by Richard Bernstein for The New York Times: “An Artist’s Famous Smile: What Lies Behind It?” (Nov. 13, 2007). See also the accompanying slideshow.

- I found Christie’s often offers extended “notes” about selling lots. See for example the note for the Yue Minjun’s painting “Boating” (1994)

- In 2007, Ana Finel Honigman wrote a plea against “cynical realism” in Chinese contemporary art. It was posted on The Guardian‘s Art&Design blog with the title “Don’t believe the hype about Chinese art”

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Painting

- Tagged: ambiguity, animal, capitalism, China, communism, cynical realism, cynicism, distance, happiness, history, indifference, man, neutral, Politic, realism, representation, suspension