An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Whitney Museum of American Art: Edward Hopper, “Night Shadows”, etching: plate, 6 7/8 × 8 1/4 in. (17.5 × 21 cm); sheet, 13 5/16 × 14 1/2 in. (33.8 × 36.8 cm), 1921. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, no. 70.1048. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper.

• • •

What I find interesting in this etching, and maybe in many more of Edward Hopper’s works, is the intersection of the following elements: a human figure is set in a man-made environment, but the general impression is typically not one of welcomeness, comfort or fulfillment. Either the figure does not fit the place, or the place does not fit the figure. Something seems to be broken or dislocated and there’s a general sense of withdrawal or of absence. In “Night Shadows” a feeling of anxiety or anguish emanates from the empty streets, populated only by half-lit shadows.

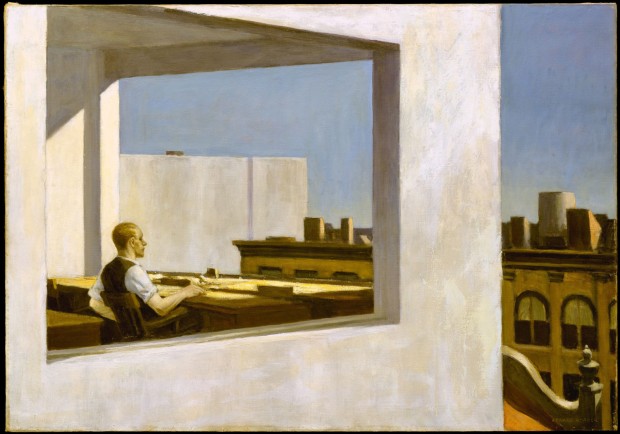

In a later painting, “New York Movie” (1939), an usherette is seen self-absorbed, forgotten on the right side of the painting, as if absent to herself. Something similar also applies to “Morning Sun” (1952) and “Office in a Small City” (1953) where the characters –female in one, male in the other– are presented in an uncanny although serene stillness. It is as if all the tensions, but also all the meanings and the general sense of direction or purposefulness that usually drives people forward had left the frame of those paintings. The fact that “Office in a Small City” once illustrated the cover of a French edition of Melville’s Bartleby shouldn’t come as a surprise (Flammarion, 1993; Amazon). I sometimes have similar impressions when I look at a the photography of Stephen Shore (see for example “Ginger Shore, Causeway Inn…”).

Walls, homes and cities were all built in order to create a more hospitable environment for human life. The city in particular is sometimes credited as the apparatus which allowed human political nature to actualized itself. This political nature is, in turn, what allows human beings to coexist in a civilized manner1. Hopper’s art could be read as a standing testimony to the fact that things are far from being that simple. His drawings and paintings often record –it seems to me– the partial failure of human coexistence in urban landscape. They offer a window on those who do not fit, are left alone or remain unable to relate. This association between individual alienation and modern cities is not new, but it remains today one of the driving force behind various nostalgic conceptions of a past, idealized coexistence2. Faced with loneliness and isolation, habitants of the cities dream about warmer ways of being together.

• • •

Between 1915 and 1928, prior to turning exclusively to painting, Edward Hopper produced about 70 etchings and dry point drawings (see MoMA). “Night Shadows” is unique in that matter. Hopper usually printed only a very small number of each of his drawings. But this particular etching was commercially printed in very large number of editions (see the MET). Christies estimates that about 500 to 600 copies were produced. This explains why “Night Shadows” is displayed in a numerous museums and regularly featured on catalogues of various auctions. For example, two signed editions will be sold by Swann Galleries on March 8, 2013 (Sale 2272, Lot 335 and 351): price is estimated between $25,000 and $50,000.

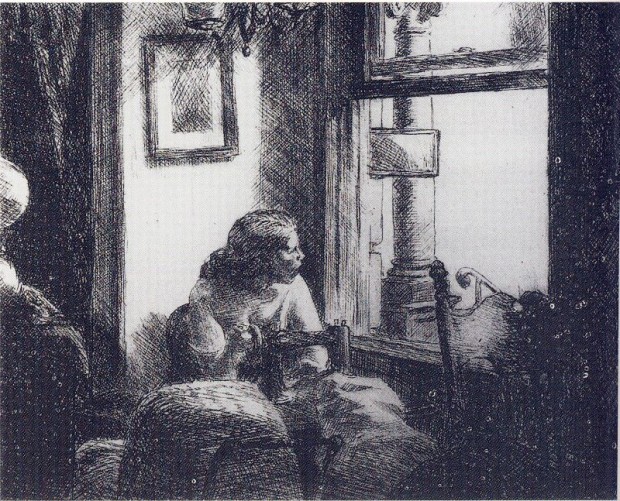

In Edward Hopper 1882–1967: Transformations of the Real Rolf Günter Renner describe the aesthetic quality of “Night Shadows”:

By the end of the 1920s, Hopper’s pictures of houses, landscapes and city scenes had already acquired and emblematic function, standing for the condition of human life. A painting done in 1927, The City, is characteristic in this respect.

To an extent it is a self-quotation, alluding to earlier drawings such as the 1921 Night Shadows, in which Hopper had used dramatic perspective and diagonals to establish an unusual compositional structure that reminds us of his debt to Edgar Degas. The dramatic impact of Night Shadows derives from the angle at which we see the nighttime walker, his shadow, and the tree’s shadow. This last is not only outside; it also intersects the right angle of the street corner almost precisely in the middle, as if the composition were a geometrical exercise. Central perspective is subverted. The tree’s shadow cuts across an almost white area at the left of the picture. It is a dynamic composition, and it generates an unmistakable sense of menace, as if the man’s walking route (which is taking him into the brightly-lit area) were taking him beyond a divide and into a danger zone. (Hamburg: Benedikt Taschen, 1990, p. 41)

In another book, The Lure and Truth of Painting: Selected Essays on Art, art critic Yves Bonnefoy offers a more general appreciation of three of Hopper’s etchings. His impressions are not entirely dissimilar to the one shared by Renner:

The series of subjects Hopper tackled in his etching certainly confirms that his technique allowed him to express obsessions and anxieties which until then he had not wanted, of had not been able, to evoke, except, perhaps, and then only fleetingly, in On the Quai, a crayon drawing of a body pulled from the Seine.

Such subjects are found, for example, in Evening Wind of 1921 and East Side Interior of 1922, two images of a young woman who seems afraid, as she stares at her open window. In the first, she is on her bed, naked and alone, and the wind has raised the window curtain, allowing entry, perhaps, to the bird who cries “Nevermore”.

In the second, it is Vermeer’s lacemaker―Hopper had seen the painting in the Louvre―who, now a simple dressmaker working in a gloomy room on more mechanical tasks, is torn from her labor by an event outside, which I’m tempted to understand, at its most profound level, as the sudden syncope of color. The works, and such others as Night in the Park or Night Shadows of 1921, express loneliness, but less in relation to other human beings―for example, Night in the El Train (1918) brings together two people who seek refuge in one another―than in terms of this nocturnal world, rustling with evil forces, which one might have thought all but forgotten. (University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 148)

• • •

Previously:

- Michael Harrington’s paintings: where “New York Movie” (1939) is briefly discussed.

- “Q Train” Nigel Van Wieck (1990): where a painting by Nigel Van Wieck is compared to Hopper’s “Summer Interior” (1909)

• • •

1. I’m specifically thinking of the ancient Greek polis or city-state, but this is not a simple matter. For a good introduction to the complexities associated with the various interpretations of this concept, see The polis-state: definition and origin by M. V. Sakellariou, Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity, National Hellenic Research Foundation, 1989. Google Books (no preview).

The story of how and why humans first came to live together in cities to avoid being killed by wild beast is told in Plato’s Protagoras. In Plato’s version of the story, it then became necessary for Zeus to provide all men with civic art in order to prevent them from killing each others while living in such proximity. (see 322a-c) ↩︎︎

2.This nostalgia for a lost “community” which is believed to be organically better than our modern “society” has received one of its most emblematic representations in Ferdinand Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887). A preview of the English translation is available on Google Books. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication, Illustration

- Tagged: absence, alienation, city, community, drawing, Edward Hopper, environment, fall, loneliness, opening, Politic, sense, space, withdrawal