An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Hannah and Her Sisters by Woody Allen, United-States, 1986, @ 00:59:38. IMDb.

• • •

In The Sense of the World first published in French in 1993, Jean-Luc Nancy opens with the following observation:

There is no longer any world: no longer a mundus, a cosmos, a composed and complete order (from) within which one might find a place, a dwelling, and the elements of an orientation. Or, again, there is no longer the “down here” of a world one could pass through toward a beyond or outside of this world. There is no longer any Spirit of the world, nor is there any history before whose tribunal one could stand. In other words, there is no longer any sense of the world. (tr. Jeffrey S. Librett, Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 1997, p. 4)

Although Nancy does not use this very word, he adds, in an accompanying note, a comment to the effect that this absence of sense is, today, quite common: it is shared by many, it has become quite familiar:

The expectation, demand, exigency, or disquietude of sense do not cease to insist today in the most current and quotidian manner: one could easily put together an anthology of phrases and this theme, simply gathered in the course of the reading of journals, and in highly diverse contexts, political, religious, economic, and so on. (Ibid., note 6, p. 171-172)

• • •

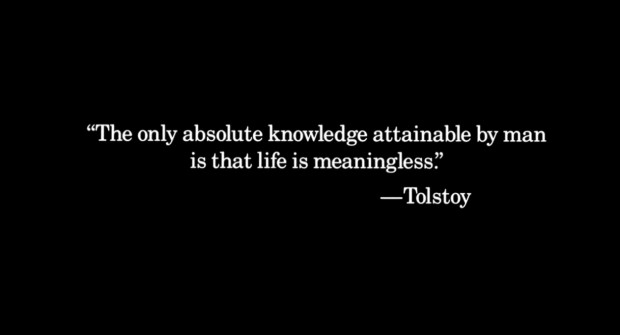

Hannah and Her Sisters won three Oscars in 1986 (Best Actor in a Supporting Role, Best Actress in a Supporting Role and Best Writing, Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen). The quote displayed in the film actually comes from Leo Tolstoy’s Confession (Исповедь) first published in Geneva in 1884 (an earlier attempt was made in 1882, but it was blocked by Orthodox Church censorship). The quote fits the English translation by David Patterson published in 1983 which Woody Allen may have consulted.

In fact, the whole sequence which follows this quote in the movie –where Woody Allen explains how he had read great authors only to discover they didn’t knew anything more than him about the meaning of life― is directly inspired by Tolstoy’s thoughts as he expressed them in his Confession:

I searched all areas of knowledge, and not only did I fail to find anything, but I was convinced that all those who had explored knowledge as I did had also come up with nothing. Not only had they found nothing, but they had clearly acknowledged the same thing that had brought me to despair: the only absolute knowledge attainable by man is that life is meaningless. (Confession, tr. by David Patterson, New York: W.W. Norton, 1983, pp. 33-34)

Compare to Woody Allen voice-over in the film, immediately following Tolstoy’s quote:

Millions of books written on every conceivable subject by all these great minds but none of them knows anything more about the big questions of life than I do. (dialogue transcript from Hannah and Her Sister via Script-O-Rama)

Of course, Woody Allen being Woody Allen, he quickly diverges from Tolstoy’s train of thought in favor of some jokes…

• • •

The realization that life is meaningless is a recuring topic in Tolstoy’s Confession. Here are some more relevant quotes:

If a fairy had come and offered to fulfill my every wish, I would not have known what to wish for. If in moments of intoxica tion I should have not desires but the habits of old desires, in moments of sobriety I knew that it was all a delusion, that I really desired nothing. I did not even want to discover truth anymore because I had guessed what it was. The truth was that life is meaningless. (Confession, tr. by David Patterson, New York: W.W. Norton, 1983, p. 25)

It was good for me to rejoice when in the depths of my soul I believed that my life had meaning. Then this play of lights and shades, the play of the comical, the tragic, the moving, the beautiful, and the terrible elements in life had comforted me. But when I saw that life was meaningless and terrible the play in the mirror could no longer amuse me. No matter how sweet the honey, it could not be sweet to me, for I saw the dragon and the mice gnawing away at my support. (Ibid., p. 29)

The third means of escape is through strength and energy. It consists of destroying life once one has realized that life is evil and meaningless. Only unusually strong and logically consistent people act in this manner. Having realized all the stupidity of the joke that is bei!:lg played on us and seeing that the blessings of the dead are greater than those of the living and that it is better not to exist, they act and put an end to this stupid joke; and they use any means of doing it: a rope around the neck, water, a knife in the heart, a train. (Ibid., p. 51)

“Life is an absurd evil; there is no doubting this,” I said to myself. “But I have lived, and I am still living; and all of humanity has lived and continues to live. How can this be? Why do men live when they are able to die? Can it be that Schopenhauer and I are the only ones brilliant enough to have realized that life is meaningless and evil?” (Ibid., p. 53)

Comparing Leo Tolstoy to Friedrich Nietzsche is a delicate operation for various reasons1. That being said, it can be interesting to think about Tolstoy’s views on the meaninglessness of life alongside the following remark made by Nietzsche in The Gay Science (first published the very same year Tolstoy attempted to publish his Confession):

When thus we reject the Christian interpretation, and condemn its “significance” as a forgery, we are immediately confronted in a striking manner with the Schopenhauerian question: Has existence then a significance at all?–the question which will require a couple of centuries even to be completely heard in all its profundity. (The Gay Science, tr. by Thomas Common, New York: The MacMillian Company, 1924, V, §357, p. 308-309)

• • •

Previously:

- “On Madness” or “On Insanity” by Leo Tolstoy, 1910

- More posts featuring Woody Allen’s work.

• • •

1. See in The Slavonic Review: “Tolstoy and Nietzsche” by Janko Lavrin, Vol. 4, No. 10, Jun. 1925, pp. 67-82. Subscription may be required for full access. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication, Movies

- Tagged: irrational, Jean-Luc Nancy, Leo Tolstoy, life, meaning, meaningless, sense, Woody Allen