An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

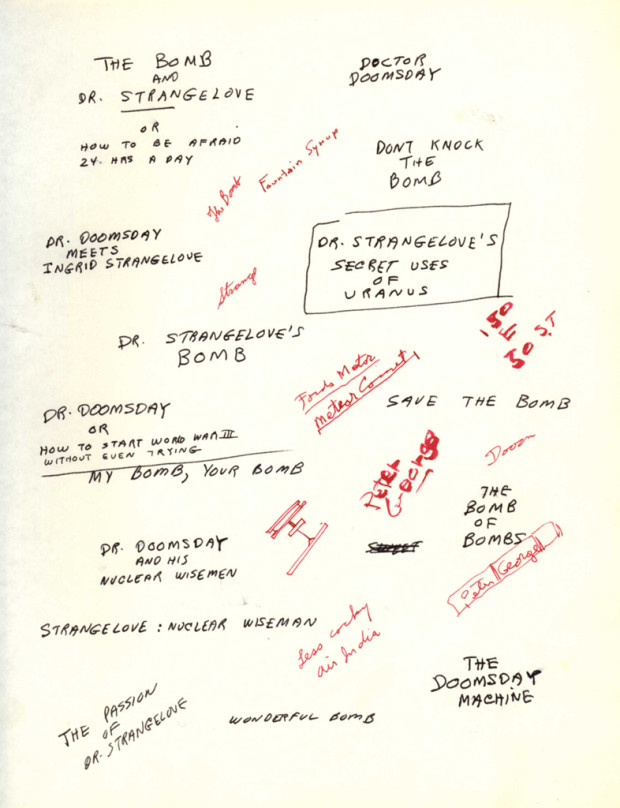

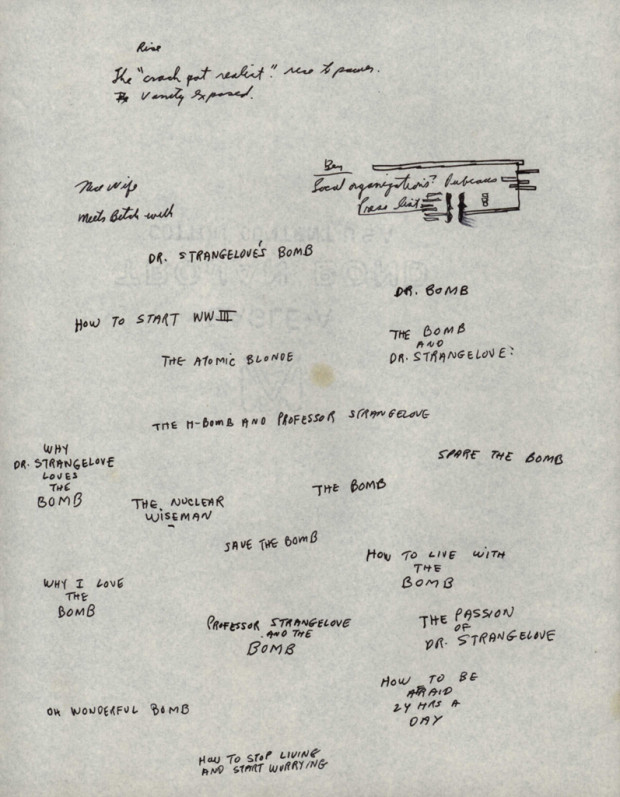

☛ LACMA – Stanley Kubrick: “Early brainstorming on titles and subtitles for Dr. Strangelove.” Photo courtesy of the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of the Arts, London. Included in the “Kubrick” app launched in 2013, in conjunction with the exhibition “Stanley Kubrick” (previously here).

• • •

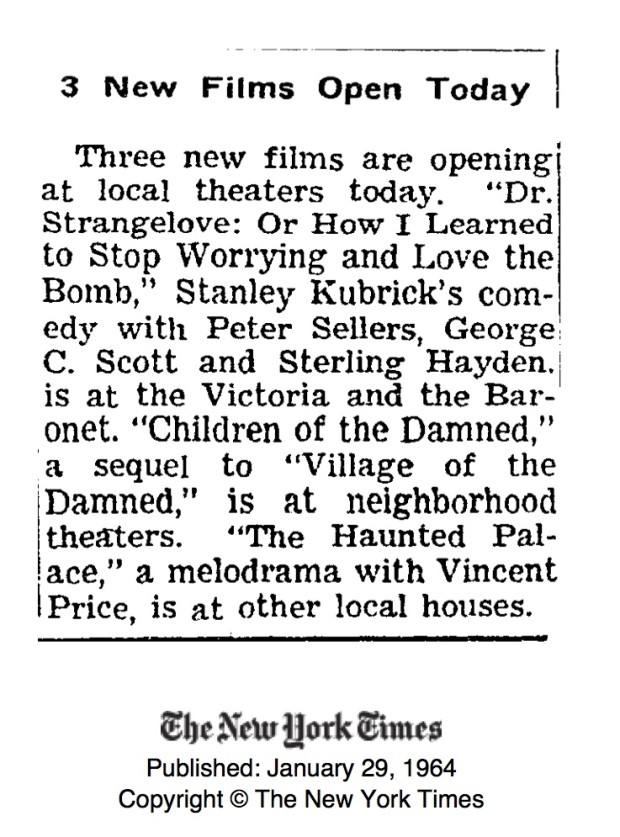

This newspaper clipping from The New York Times reads as follow:

Three new films are opening at local theaters today. “Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” Stanley Kubrick’s com edy with Peter Sellers, George C. Scott and Sterling Hayden. at the Victoria and the Bar onet. “Children of the Damned,” a sequel to “Village of the Damned,” is at neighborhood theaters. “The Haunted Pal ace,” a melodrama with Vincent Price, is at other local houses. (“3 New Films Open Today”, January 29 1964)

Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb opened 51 years ago today, on January 29, 1964. Even before it was first screened, the film was already deeply entangled in the political context of its time. The premiere, which was originally scheduled for December 12, 1963, had to be cancelled following the very recent assassination of President Kennedy (on November 22, 1963). When it finally opened in New York a month and a half later, the intense reactions it causes brought to light just how sensible the film’s main themes were. The day after it premiered, New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote:

Stanley Kubrick’s new film, called “Dr. Strange love or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” is beyond any ques tion the most shattering sick joke I’ve ever come across. […] My reaction to it is quite divided, because there is so much about it that is grand, so much that is brilliant and amusing, and much that is grave and dangerous. (“Kubrick Film Presents Sellers in 3 Roles”, Jan. 30, 1964)

Reacting to the review in a “letter to the editor”, philosopher of technology Lewis Mumford argued:

It is not this film that is sick: what is sick is our supposedly moral, democratic country which allowed this policy to be formulated and implemented without even the pretense of open public debate.” (The New York Times, March 1st, 1964, section 2, p. 8).

Meanwhile, the public had apparently made his choice. On February 5th, 1964, Variety’s front page read in all-capitals letters: “FLASH! STANLEY KUBRICK’S DR. STRANGELOVE BREAKS EVERY OPENING-WEEK RECORD IN HISTORY OF VICTORIA THEATRE (NEW YORK), BARONET THEATRE (NEW YORK), COLUMBIA THEATRE (LONDON)”.

For more about the context in which Dr. Strangelove was produced and released, see Vincent LoBrutto’s Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (Da Capo Press, 1999, pp. 227-251), as well as Jeremy Boxens`s essay “Cold War Purging, Political Dissent and the Right Hand of Dr. Strangelove” (from 1995).

To learn more about the film’s iconic opening title sequence, visit the always-excellent website Art of the Title.

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Movies, Technology

- Tagged: atomic, bomb, cold war, Kubrick, nuclear, Stangelove