An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

For we indeed do not at all essentially partake of being; but every mortal nature, being in the midst between generation and corruption, exhibits an appearance, and an obscure and weak opinion of itself. And if you fix your thought, desiring to comprehend it, — as the hard grasping of water, by the pressing and squeezing together that which is fluid, loses that which is held, — so when reason pursues too evident a perception of any one of the things subject to passion and change, it is deceived and led away, partly towards its generation and partly towards its corruption, being able to apprehend nothing either remaining or really subsisting. For we cannot, as Heraclitus says, step twice into the same river, or twice find any perishable substance in the same state; but by the suddenness and swiftness of the change, it disperses and again gathers together, comes and goes. Whence what is generated of it reaches not to the perfection of being, because the generation never ceases nor is at an end; but always changing, of seed it makes an embryo, next an infant, then a child, then a stripling, after that a young man, then a full-grown man, an elderly man, and lastly, a decrepit old man, corrupting the former generations and statures by the latter. But we ridiculously fear one death, having already so often died and still dying. For not only, as Heraclitus said, is the death of fire the generation of air, and the death of air the generation of water; but you may see this more plainly in men themselves; for the full-grown man perishes when the old man comes, as the youth terminated in the full-grown man, the child in the youth, the infant in the child. So yesterday died in to-day, and to-day dies in to-morrow; so that none remains nor is one, but we are generated many, according as matter glides and turns about one phantasm and common mould. For how do we, if we remain the same, delight now in other things than we delighted in before? How do we love, hate, admire, and contemn things contrary to the former? How do we use other words and other passions, not having the same form, figure, or understanding? For neither is it probable we should be thus differently affected without change, neither is he who changes the same. And if he is not the same, neither is he at all; but changing from the same, he changes also his being, being made one from another. But the sense is deceived through the ignorance of being, supposing that to be which appears.

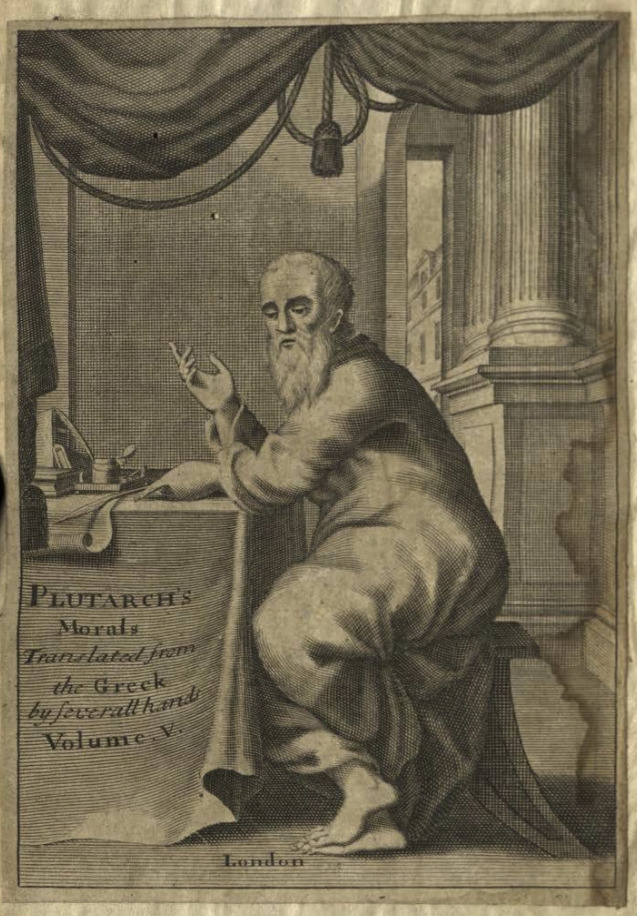

☛ Plutarch, Plutarch’s Morals. Translated from the Greek by Several Hands. Corrected and Revised by William W. Goodwin, with an Introduction by Ralph Waldo Emerson. 5 Volumes. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1878). Vol. 4. “Of the Word Ei Engraven Over the Gate of Apollo’s Temple At Delphi”, §18. Google Books preview: 1704: p. 464; 1874: p. 493.

When working with Plutarch’s Morals, the volumes available at the Online Library of Liberty are very useful (various formats are available: from HTML to PDF of facsimiles to ePub). Some volumes are also available at the Internet Archive. For more images of the frontispiece, see this Flickr set. Also interesting to note is this mention on the title page: “Translated from the Greek by Several Hands”.

And below is the French version:

Pour nous, l’existence n’est pas proprement notre partage. Toutes les substances périssables placées, pour ainsi dire, entre la naissance et la mort, n’ont qu’une apparence incertaine, et existent dans notre opinion plutôt qu’elles n’existent réellement. (392b) Veut-on appliquer son esprit pour les saisir par la pensée ? il en est d’elles comme d’un liquide qu’on presse dans ses mains ; à mesure qu’on le serre davantage, il s’écoule et se perd. Ainsi la raison, en voulant se former une idée évidente des substances passibles et muables, s’égare nécessairement, parce qu’elle s’attache à leur naissance ou à leur mort, sans pouvoir saisir en elles rien de permanent et qui ait une existence réelle. On ne descend pas deux fois dans le même fleuve, dit Héraclite (35). On ne trouve pas non plus deux fois dans le même état une substance périssable. Telle est la rapidité de ses changements, qu’un instant en réunit les parties et un instant les disperse ; elle ne fait que paraître (392c) et disparaître. Aussi ne parvient-elle jamais à un état qu’on puisse appeler existence, parce qu’elle ne cesse point de naître et de se former. Passant depuis le premier instant de sa conception par des vicissitudes continuelles, elle est successivement embryon, être animé, enfant, adolescent, jeune homme, homme fait, vieillard et décrépit. Une génération nouvelle détruit sans cesse les précédentes. Après cela, n’est-il pus ridicule que nous craignions la mort, nous qui sommes déjà morts tant de fois et qui mourons tous les jours? Héraclite disait que la mort du feu était la naissance de l’air, et que la mort de l’air donnait naissance à l’eau. Mais cela se vérifie bien plus sensiblement en nous-mêmes. L’homme fait (392d) meurt quand le vieillard commence ; et il n’avait lui-même existé que par la mort du jeune homme, et celui-ci parcelle de l’enfant. L’homme d’hier est mort aujourd’hui, et celui d’aujourd’hui mourra demain. Il n’est personne qui subsiste et qui soit toujours un. Nous sommes successivement plusieurs êtres, et la matière dont nous sommes formés s’agite et s’altère sans cesse autour d’un simulacre et d’un moule commun. En effet, si nous demeurons toujours les mêmes, pourquoi changeons-nous si souvent de goûts ? Pourquoi nous voit-on aimer, haïr, admirer, blâmer tour à tour les objets les plus contraires, varier à tous moments dans nos discours, nos sentiments, nos affections, (392e) et jusque dans notre figure ? Il n’est pas vraisemblable que cette diversité dans notre manière d’être se fasse sans quelque changement, et quiconque change n’est pas le même : s’il n’est pas le même, il n’a donc pas proprement l’existence ; mais par des changements continuels il passe d’une manière d’être à une autre. Nos sens, par l’ignorance de ce qui est réellement, nous font attribuer la réalité de l’être à ce qui n’en a que l’apparence. (Plutarque, Oeuvres Morales de Plutarque, «Que signifie le mot Ei gravé sur la porte du temple de Delphes», traduites du grec par Ricard, à Paris, chez Lefèvre, éditeur, rue de L’Éperon, 6 – chez Charpentier, éditeur, rue De Seine, 29, 1844, 5 volumes. Tome 2)

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: change, death, existence, moral, partake, philosophy, Plutarch, time