An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

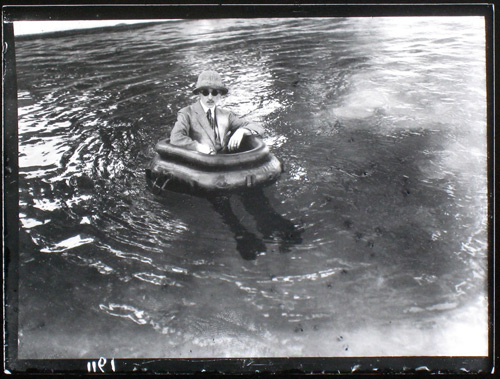

☛ “Self-portrait with hydroglider” by Jacques Henri Lartigue, Paris, 1904. This photo illustrates the cover of the book Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Boy With A Camera by John Cech, New York: Four Winds Press, 1994.

Cech adds the following details about the way this self-portrait was made:

Lartigue placed the camera on a floating board in the tube, set the exposure and focus, and had his mother snap the picture. (p. 32)

• • •

Wes Anderson openly acknowledged French photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue1 as a source of creative inspiration. For example, in the press kit (PDF) of his second film Rushmore (1998), one can read the following remarks by Anderson:

We wanted it to feel kind of like a fable, I guess; a little unreal. And we wanted to show the way Max sees Rushmore, which is a place that he loves all out of proportion with anything. And I kept thinking of period movies. Powell and Pressburger’s The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp, and also The Age Of Innocence and this Truffaut film Two English Girls. Of course, Rushmore isn’t a period movie. But it seemed like the right idea. So my cameraman Bob Yeoman, production designer David Wasco, and I watched those movies together. And we looked at some pictures by photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who reminds me of Max, and that became a part of it.

Anderson also mentioned Lartigue in 2005 when The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou opened in France:

Parlez-nous de Steve Zissou, l’océanographe en chef de cette drôle d’équipée…

Tout d’abord, je voudrais dire une chose aux spectateurs français: je ne savais pas du tout que Zissou était le nom d’un joueur de football! (rires) J’ai appris ça en arrivant ici, je jure que je n’en savais rien! En fait, un merveilleux photographe français, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, qui a fait beaucoup de photos incroyables au début du 20e siècle, avait un frère dont le surnom était Zissou. Il était souvent sur les photos, et il était absolument génial, il faisait des tas de cascades, c’était un casse-cou fini. J’ai eu envie de lui rendre hommage, même si le personnage de Zissou dans le film n’est pas vraiment un casse-cou. (Allo-Cine: “La Vie aquatique: rencontre avec Wes Anderson”, March 9, 2005).

Lartigue’s name appears in the end credits of both those films.

Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986) was a French photographer who started taking pictures at a very young age. His father offered him his first camera in 1901, when he was just 7 years old. From that point on, Lartigue never stopped taking pictures for his own amusement. His massive body of work remained unknown ―except for his immediate entourage― for most of his life. He was 69 years old when an American curator finally took some interest in his work.

Lartigue’s photos are said to encapsulated a sense of constantly renewed wonder, a childish enthusiasm for the advent of modern times2:

Lartigue’s eye was simply not tuned to any of life’s horrors and ugliness. Though he entered the army when the war broke over Europe, and served as a pell-mell staff car driver for a series of generals, there is no evidence ―either in this book or in the other Lartigue photographs which have been published or exhibited― that he ever let his camera look at death or destruction. Rather, his vision has been a joyful, exhuberant one, and has remained so over the eighty-three years of his life, through two great wars and a world-wide depression. (Jacques-Henri Lartigue, New York: Aperture, 1974, p. 5)

In Rushmore at least four of Lartigue’s photographs are referenced very early in the film. Just after the curtains open to reveal the name of Rushmore Academy, a quick panning shot shows two of Lartigue’s photos taped on one of the blackboards. They appear very briefly and are blurred by the fast movement of the camera.

The same two photos are shown again, along with two others, a couple of shots later. While Max is reading the financial section of a newspaper at his desk, he’s challenged by his teacher to an impossible mathematical problem: “Max? Care to try it?”. Upon hearing this, Max lower his newspaper and, behind him, taped to the wall are four photos by Lartigue: the two on the left are the same that are also taped on the blackboard.

In the upper left corner is a photo of Jacques Henri older brother Maurice Lartigue (whom everyone called Zissou) trying to take off in a home-made glider named the ZYX 24. The official name of the photo is “Le Zyx 24 s’envole… Dédé et Robert essaient de s’envoler aussi” (gelatin silver print, Rouzat, september 1910).

In the book Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Boy With A Camera, the photo is accompany by the following caption by John Cech:

Ever since Zissou had seen Gabriel Voisin sail over the dunes, he had wanted to fly. And so, after his early experiments with an umbrella, he built glider after glider, often using the family bedsheets to stretch across the framework of the wings. Jacques, of course, recorded all of these events with his camera, form the first jumps, to the many repairs and refinements, to the remarkable flight of Zissou in his ZYX 24 (New York: Four Winds Press, 1994, p. 22)

The flight of Gabriel Voisin took place six years before, on April 1904 and was also recorded by Lartigue in a photos titled “Premier vol de Gabriel Voisin sur l’aéroplane Archdiacon” (“Gabriel Voisin’s flight in the Archdeacon”, Merlimont, April 3, 1904). This photo also appears in John Cech’s book (p. 12).

In its issue of November 29, 1963, Life magazine features numerous photos by Jacques Henri Lartigue. A cropped version of the photo depicting the flight of the ZYX 24 is reproduced on p. 69 along with the following comment:

Having given a big push and jump, Maurice dangles from the bottom of his 22nd glider. A friend is helping by holding wings level, while another is pulling desperatly at the rope disappearing off the right edge of the picture. Longest Lartigue flight was about a minute

There are a number of additional photos by Jacques Henri showing his brother’s various attempt at getting airborn.

In another book simply title Jacques-Henri Lartigue (New York: Aperture, 1976) Ezra Bowen comments the same photo in her introduction:

Does anything say more of the dreamlike excitement of that time, of the confidence and romantism of the people? Or indeed of the sure eye and brilliant sense of timing of the sixteen-year-old photographer who not only captured the moment, but saw in it the combination of verve and marvelous farce that are part of so many of his other pictures? (p. 6)

Next, in the upper right corner is another photo of Zissou in one of his curious invention: the tire boat.

The photo is sometimes simply titled “Zissou” (Rouzat, 1911) or “Zissou dans son bateau pneu” (“Zissou in his tire boat”, Chateau du Rouzat, 1911). In John Cech’s book it appears with this caption:

Not all of Zissou’s inventions required heroic feats. Here, he is trying out the latest in inner tubes. This one had rubber legs and feet built into itso that he could wear his suit and tie while floating in the water.” (New York: Four Winds Press, 1994, p. 24)

In the same Life magazine issue (November 29, 1963) the photo is also reproduced with this comment:

The Lartigue had a passion of odd boats. Maurice tries out a raft whose bottom is a pair of rubber boots. He walked in the pool’s shallow end, thrashed his legs in deep water. (p. 70)

Jacques Henri Lartigue always kept very detailed diairies of his photographic activities, writing about the weather and sketching the outlines of each one of the photographs he had taken during the day. Below is the reproduction of the page pertaining to the day he took the picture of Zissou in his tire boat (also retrieved from John Cech’s book, on page 25).

Next, in the lower right corner behind Max, is one of the most easily recognizable homage by Wes Anderson to Jacques Henri Lartigue. Indeed, this photo is also recreated a couple of minutes later in the film, with Max actually taking the place of Zissou. Lartigue’s photo actually depicts his older brother sitting in front of his broken “bob” or “bobsled” on wheels (similar to a “soapbox”: it steers and breaks but runs on gravity alone, racing down slopes and such). The title assigned by the Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue is “Le bobsleigh à roues de Zissou, après le virage de la grille” (“Zissou’s bobsled with wheels, after the bend by the gate”, Rouzat, August 1908; some sources such as John Cech’s book date this photo from 1909 instead of 1908).

Below is the portrait of Max posing as the Founder of the Yankee Racers. It is closely modeled after Lartigue’s picture:

Finally, in the lower left corner, there’s the famous speed-distorted photo of the racing car passing through the frame: “Grand Prix de l’A.C.F. Automobile Delage” (“A Delage racer at the Automobile Club of France Grand Prix race”, Circuit de Dieppe, 26 juin 1912). The photo was prominently featured in the issue of Life magazine I already mentionned, spreading on two pages (67-68).

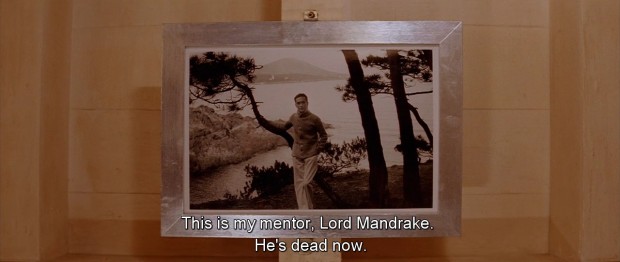

And then there’s the references in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), Anderson’s fourth feature film (it came out after The Royal Tenenbaums in 2001 and before The Darjeeling Limited in 2007). The name for the character played by Bill Murray is a direct reference to Lartigue’s older brother. Also, a self-portrait taken by Jacques Henri Lartigue in 1919 is identify by Steve Zissou (Bill Murray) as a picture of his dead mentor Lord Mandrake. The photo is actually titled “Jacques-Henri Lartigue” or “Moi au Cap du Dramont” (Agay, Cap du Dramont, mars 1919). A low resolution version of the original can be found over at Simon Studer Art.

• • •

To learn more about Jacques Henri Lartigue, consider exploring the following links:

-

The right place to start is the official Donation Jacques-Henri Lartigue website (better with Flash):

In 1979 Jacques Henri Lartigue donated his entire photography collection to the French nation and entrusts the “Association des Amis de Jacques Henri Lartigue” known as «Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue» to preserve, enhance and promote his work.

There isn’t a large collection pf photos available, but instead a biography, chronology of Latrigue’s life, a bibliography, an expography and a filmography. 22 iconic prints of Lartigue’s work are available in medium format along with adequate attribution.

-

See an essay by Stuart McClintock, Professor of French at the Midwestern French University: “Texas Francophile: French Influences in the Films of Wes Anderson” (.DOC, PDF)

-

Over at Film’s Not Dead one can watch two different documentary through YouTube embedded video: The Boy Who Never Grew Up (BBC, 2009) and an older documentary from the BBC series Master of Photographers (1983).

-

Life magazine from November 29, 1963 is available through Google Books. Lartigue’s feature starts on page 65 (PDF). This is the often-cited issue that helped promoting Lartigue’s work in the United-States.

-

LiveJournal has a great collection of 51 large format photos by Jacques Henri Lartigue, although none are identified (except the last one: a nice portrait of Lartigue kissing Hungarian photographer George Brassaï).

-

The Photographer’s Gallery has 80 medium format photos by Lartigue, all properly identified.

-

Artnet has an even larger collection of 745 items associated with Jacques Henri Lartigue (from past auctions). Images are not presented in a large format, but the website is still useful for the informations it provides along with each one of those items.

-

G. Gibson Gallery has 56 photos of Lartigue. They are all shown is a rather small format but they all come with precise and adequate information.

-

Pixiq: “The Littlest Photographer, the Family Photos of Jacques Lartigue” by Steve Meltzer, November 15, 2011. Along with 22 large format photos (depending on the screen: the gallery is “zoomable”).

-

Photography-Now has a nice portofolio (Flash is required) of image, medium format. However, none of those photos are identfied. On the same website, one can find a short essay on Jacques Henri Lartigue: it’s mostly (slightly) re-written version of the English Wikipedia entry for “Jacques Henri Lartigue”.

-

The photo he took of his cousin “flying” down the stairs (“L’envol de Bichonnade”, 40 rue Cortambert, Paris, 1905) is discussed in the BBC series Genius of photography (in the episode “Fixing the Shadow”).

-

Oswal Gallery has 14 photos by Lartigue, small to medium format along with adeqate information.

-

Staley Wise Gallery has 10 photos, along with proper information.

-

Fifty One Fine Art Photography Gallery has five photos along with a biography.

• • •

1. “Jacques Henri” is sometimes spelled with an hyphen, sometimes without it. Throughout this entry, I’m using the spelling found on the official Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue website, except in quotes and book titles.↩︎︎

2.He was once compared to Peter Pan: “at just seven years of age Jacques-Henri Lartigue decided to dedicate his life to the pursuit of happiness and never growing up” (Michael Hoppen Gallery). Given this reputation, I wasn’t surprise to hear The Fabulous Destiny of Amélie Poulain’s soundtrack while I was watching the documentary Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Boy Who Never Grew Up (BBC, 2009). Some may find this idealizing of the “innocent gaze” annoying, other may celebrate it. Suffice to say here that there’s a world of difference between Lartigue’s pictures and, say, those taken by Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama. For a discussion about Lartigue’s image as a genius amateur photographer with an instinctive childish eye, see Kevin Moore’s book Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Invention of an Artist (2004) or read a review of it over at Slate: “The Lartigue Hoax?” by Jim Lewis, September 15, 2004. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Movies, Photography, Technology

- Tagged: childhood, innovation, Jacques Henri Lartigue, modernity, Rushmore, Wes Anderson, Zissou