An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

This is an extended version (more than twice the size) of an peer-reviewed essay published in TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies: access the shorter version here (not open access). University of Toronto Press remains the copyright holder of the content. This essay was finalized on June 16, 2020. To quote the peer-reviewed version:

Theophanidis, Philippe. “Sua Cuique Persona: The Ambivalent Politics of Masks.” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 41 (2020): 33–41. https://doi.org/10.3138/topia-005.

• • •

1. Visualizing The Non-Medical Masks

Insofar as “theory” once meant “to look attentively” at what becomes visible, a theory of the COVID-19 pandemic would be concerned with how it is visualized1. This question is important not just for the specialized field of visual culture studies (Bildwissenshaft in German)2. On it depends our collective capacity to think about the current crisis and, just as importantly, to imagine a future beyond it3. Some systematic efforts have already been made to reflect on the many ways in which the pandemic is visually represented, such as the joint initiative between the Journal of Visual Culture and the Harun Farocki Institut (Holert 2020a)4.

This short post is concerned with a specific issue regarding the visibility of the current pandemic. One of the main characteristics of the virus remains its invisibility, which quickly spurred rhetoric about the “invisible enemy.”5 This invisibility in turn has significantly shaped many of the measures put in place in most countries to mitigate the spread of the virus: mandatory or voluntary quarantine, reduced circulation, physical distancing, hand hygiene, et cetera.6 Among those measures, one is all the more visible because it makes faces disappear: the now ubiquitous non-medical mask worn by the general population in many countries.7

It is beyond the purview of this short contribution to properly examine the rich literature dedicated to the concepts of mask and face, or to study how masks vary from one culture to another.8 Instead, I approach the function of the mask by taking a detour and examining a painting from the early 16th century.9 The goal is to bring to the fore the fundamental ambivalence of the mask, the fact that it is never merely one, simple thing, whether it is meant to express, to conceal, to protect or a combination of all of the above. Following this detour and coming back to the present situation, I suggest that the non-medical mask—which comes in many shapes—may well be primarily a response to a biological threat, but only insofar as this response also raises questions regarding politics.

2. Sua Cuique Persona

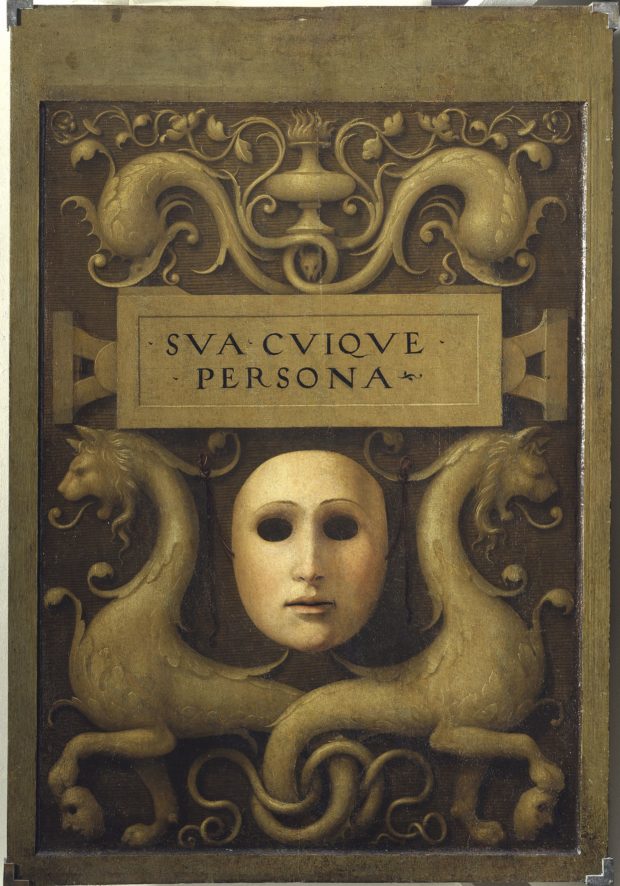

At the famous Uffizi Gallery (Galleria degli Uffizi), in Florence, there is a peculiar painting attributed to Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (1483-1561; see fig. 1).10 Dated circa 1510, it has been described as one of the most singular and enigmatic objects in the history of European painting (Baader 2000, 116). The painting depicts an elaborate composition meant to mimic a low relief sculpted in stone, probably marble. Its composition evokes Renaissance grotesque motifs, arranged symmetrically on the vertical axis. At the top are two fish-like creatures, graciously intertwined in frolicking curves, their joined tails supporting a fire urn. They in turn are teetering atop one of the two main features of the entire composition: a massive rectangular block arranged horizontally just above the middle point of the frame, on which is carved, in classic Roman square capitals, the words SVA CVIQUE PERSONA (sua cuique persona), meaning “to each his/her own mask” or “to each his/her role.”11 A bright mask—appearing to answer the Latin inscription, although equally enigmatic—is suspended just below the block. Amidst a composition that is mostly made up of deep ochre, monochromatic tones, the mask jumps to the fore and constitutes the other main feature of the entire painting. Closer inspection reveals how the mask is tied, on each side, to the horns or fins of the two sea lions or dragon-like creatures flanking it, looking away themselves (although the two leather-like cords securing the mask do not seem to be under tension from its weight). The mask’s features are very delicate. Cheeks and lips show subtle pink shades, giving it an almost lifelike appearance; the mouth is half open as if it is about to speak; the nose is rendered realistically, and seems to protrude slightly from the mask’s otherwise very smooth surface; individual hairs can even be discerned in the thin eyebrows painted above the eyes. However, in this detailed depiction of a human face, one crucial feature is strikingly missing: two gaping holes are found where one would expect to see gleaming eyes.

Fig. 1—Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Sua Cuique Persona, c.1510. Oil on panel, 73 × 50 cm, Uffizi Galleries, Florence. Source.

As if to further underline the centrality of the mask, the two larger sea creatures—both with graciously sinuous bodies—also hold smaller masks under their lionlike paws: they too have their own disguises. Upon further consideration, the whole painting seems to be made up of multiplying, contrasting doubles. The central mask is not only contrasted to the (absent) face it is supposed to cover: its delicate, lifelike features are also in contrast to the pseudo-marble low relief it is set against. The stony hardness of the pseudo-marble is, in turn, set in contrast against the many curves shaping the four sea creatures.

All of this should be enough to make this work an intriguing and interesting painting in and of itself. But this is not merely a painting: it is also an artifact (Belting 2017, 93–94). It is, in other words, an object with a specific and rather unique function: it was meant to cover a portrait and is known as a copertura or tirella. As such, it was designed to protect and conceal an actual portrait, which it would slide over. What needed protection was not only the physical integrity of the work of art, but the sheer sight of it; a portrait covered in such a way was not meant to be exposed all the time. The exact identity of this secret portrait is not known, and might have been lost (Baader 1999, 239). In the 19th century, the cover was paired with the painting of a veiled woman then attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. While the creator of this portrait, known as La Donna veleta (“The veiled woman”) or La Monaca (“The Nun”) is still disputed, it was later also attributed to Ghirlandaio (Natali 1995; Fossi 2009, 117).12 It is with this attribution that is being exhibited at the Uffizi Gallery (see fig. 2).13

Before proceeding to non-medical masks, let us focus on the cover portrait for a brief moment. Two remarks will allow us to think about—and therefore imagine—differently our relationship to our current masked predicament. The first set of remarks pertains to the visual composition, while the second focuses more specifically on the inscription. The mask, with its delicate features and vivid colours, seems to teeter on the verge of being the living face of a person, yet it reveals nothing but the very dark background it rests against.14 This negative feature could make it impossible to mistake the mask for an actual face.15 Instead, it is as if the mask is working toward the suspension of the common distinctions between presence and representation, life and death, persons and things, exposition and concealment, identity and difference (Schulz 2013, 46–47).16 This unsettling unity—of what is usually considered distinct—further extends to the rest of the composition. Indeed, the mask, which is not the face of any specific person, is not an actual mask either: it is not the real thing, but an image of a thing. Nevertheless, this image of a mask is not just an image; it is also an artifact, a physical wood panel meant to cover something else. What it conceals, once revealed, is not an actual person, but an illusion: a painted portrait. Each time, the composition at once presents itself for what it is, and yet does so while strongly evoking what it is not.17 To put it differently, the painted mask exposes its proper and true nature as the staging of a difference. In doing so, it unsettles a tradition that consistently, yet problematically, makes the face the core of a stable identity.

The ancient Greeks used a single word—prosopon—to convey a wide variety of meanings including (but not restricted to) face, mask, and the person playing a role (Nédoncelle 1948; Napier 1986, 8; Frontisi-Ducroux 1995; Fischer 2001; Ildefonse 2009). In contrast, the Romans introduced a distinction between the bare human being and its various personae, or masks (De Lacy 1977, 32–35; Esposito 2012a, 10–11; 2012b, 25).18 The distinction was important, as it granted a positive, legal qualification only to the latter, creating a category of humans that were non-persons (Heller-Roazen 2009, 147-48). In early modernity, another division separated the Roman conception of personhood from the mask (Esposito 2012, 11). In the process, the mask became an object capable, among other things, of hiding or altering a person’s appearance (Esposito 84–85; Belting 2017, 97). Hence, the value of the mask underwent an inversion, from having the positive value of the Roman persona to an artifact with the negative function of falsifying the truth (Lechte 2012, 68–72).19 Since then, masks have been considered in light of a dialectical scheme characteristic of Western thought where appearance is opposed to reality, truth to falseness and surface to depth. However, insofar as public life demands that we participate as “persons,” the persona is not secondary to how we present ourselves to one another: it is who we are. The juridical importance of the status of personhood in contemporary times still carries this valence. As Raymond Williams once observed, the implicit relationship between mask and persona “can still haunt us today,” although the face holds a privileged relationship to the idea of personal identity (1976, 223). While all these remarks remain insufficient, they shed some light on the ambivalence of the notion of “mask,” and can help in understanding its contemporary relation to politics. The cover portrait at the Uffizi Gallery, produced at the turn of the 16th century, is emblematic of this ambivalence.

3. The Ambivalent Politics of Masks

Returning from the distant cinquecento, it is now possible to briefly examine two aspects of the non-medical mask. The first has to do with the politics of a mask that is otherwise associated with a biological function. The second follows from the first, and is concerned with the asymmetry exposed by a mask that is otherwise seen as having a generic value, fulfilling the same function for all those who wear it.

From the outset, it is tempting to argue that wearing a non-medical mask solely for its hygienic function reduces our personal identity to its biological core. If the face—its exposition and its sight—is what provides our relationships with political dimensions, then covering it could amount to masking what makes us more than mere living bodies. However, this interpretation oversees the intimate way politics has come to intersect with biological life in recent times. Certainly, “biopolitics” has been a prevalent concept, naming how life is captured by political means. In the case at hand, I suggest there is an upside to this predicament. The non-medical masks we wear do not merely cover our faces. They also, at the same time, expose and make visible something beyond sheer bodily function, having more to do with an ethic of togetherness. For the sake of brevity, I will refer to this as the politics of the mask, although elsewhere it is worth asking if the idea of “politics” is still relevant, or if it is overwhelmed and superseded by an excess pointing to something else, aside from, beyond or below the political.20

The fact that the mask as a (necessarily artificial) artifact does not preclude political participation is supported by a large variety of recent examples. Ghirlandaio’s enigmatic painting was, after all, appropriated as an emblem and used as a frontispiece in the first two issues of Tiqqun, a short-lived French journal of political philosophy edited by an anonymous group. From their perspective, the locution sua cuique persona names the fact that in the present reality, disguises do not mask the truth but are rather constitutive of it (Tiqqun 2012, 74). Masks were used and targeted by anti-mask laws in a variety of recent political movements, from the Occupy movement to the ongoing 2019–20 Hong Kong protests. Each time, the masks implicated in these protest movements assumed a variety of functions, including protection from tear gas used by law enforcement agencies. They were also used by protesters simply, but critically, to prevent their identification. This did not exclude individuals from political participation: on the contrary, it was, in many cases, a condition for their safe participation in public. Under those circumstances, masks pre-empt the capture of manageable identities by the State, while making the unidentifiable nonetheless visible in the public sphere.21 Since the start of the global pandemic, the issue of just how non-medical masks intersect with various technologies of facial recognition has come under scrutiny (Murphy and Titcomb 2020). Doubling the use of various face masks, applications have been developed to automatically blur the faces captured by a smartphone camera in case the device is seized by law enforcement agencies (Bishara 2020).22 In this context, it did not take long for non-medical masks to become the centre of heated debate. Despite calls to not “turn public-health tools into symbols,” it quickly became patent that masks could not be constrained within the strict sphere of biology (Friedersdorf 2020). More than one commentator has brought attention to the extent to which non-medical masks have become a “cultural icon” and the “symbol of our times” (Unni 2020; Friedman 2020).

However, almost as soon as they covered faces, non-medical masks also uncovered or made strikingly visible flagrant asymmetries in the various ways the pandemic was experienced and lived worldwide. This goes against the commonly received idea “that the ‘facelessness’ increases solidarity and decreases indications of class, race, gender” (Borum and Tilby 2005, 216). In this light, the mask is not a straightforward solution, neither to the pandemic nor to the current (bio)political crisis. Its intrinsic ambivalence should prohibit its sacralization and glorification as a tool for or symbol of unequivocal political resistance. The non-medical mask shared among various populations is not a vector of unification, nor a “great equalizer.” Instead, like a chemical catalyst used in photographic processing to turn a latent image into a visible one, the non-medical mask that has become ubiquitous since the start of the pandemic further reveals fractures and gaping inequalities. It shows that while we might be “all in this together,” as a popular but problematic slogan suggests, “we” are certainly not all in it the same way (Arthur 2020). While examples abound, I will limit myself to a selection of illustrative cases.

The irony that not so long ago in various contexts, but prominently in France and the province of Quebec (Canada), laws were adopted to ban the use of full-face veils in public, while legislation has been passed to make it illegal to enter these same public spaces without wearing a mask, has not been lost to observers (Pelletier 2020; Bullock 2020; Sealy 2020; Stoppard 2020). This is far from being the only context in which double standards are being exposed by non-medical masks. In the United States, non-medical masks have become a “flashpoint” in a “culture war” pitting proponents of masks against those who believe they should have the (individual) freedom not to wear any (Canales 2020; Dickson 2020; Rojas 2020; Shepherd 2020).23 What is brought to the fore in the process is just how much the pandemic amplifies divisions of all sorts: not only in political views, but also economic status, social class and race. While wearing a mask might appear to be an individual choice to some, it is clear that in many cases it is a necessity imposed by socio-economic disparities (Bascaramurty et al. 2020; Dorn et al. 2020; Fisher and Bubola 2020).

Those differences were further highlighted in the wake of the massive George Floyd protests that took over the streets of many cities all over the world (ongoing at the time of writing). Two aspects related to wearing masks in the context of protests against police brutality are worth underlining. The first one was present from the start of the pandemic, but jumped to the fore when the protests against police brutality started. People of colour who chose to wear non-medical masks—as was advised, in many cases, by the authorities—ran risks that white protesters were not likely to experience. In those instances, non-medical masks cannot be reduced to their role in curbing the spread of the COVID-19 virus: they carry an excessive political weight that can work against those who opt to wear them, as has been amply documented (Cineas 2020; De La Garza 2020; McFarling 2020; Taylor 2020). The second aspect is based on visual evidence, and further underlines the fact that all masks are not made equal. In many U.S. cities, protesters wearing non-medial masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19 are confronted with militarized law enforcement agents often wearing full tactical gear.24 These include face shields and gas masks (or full-face respirators). This gear also prevents the identification of the agents wearing it, while offering them additional physical and biological protection.25 The discrepancy between the types of masks used by protestors and police was strikingly illustrated in a now-iconic picture shared by photographer Dai Sugano on his Instagram account on May 29, 2020. It shows a single young black protester taking a knee in front of a row of law enforcement officials during a protest in San Jose, California. While the protester wore a generic pale blue non-medical mask, all the officers visible in the frame wore tactical helmets equipped with face shields.26 There was nothing equal in the conditions of this masked encounter.

4. A Shared Immunity Machine

The non-medical masks we wear are not as enigmatic as the one displayed on the copertura attributed to Ghirlandaio, but they too confront us with difficult problems. While there is little doubt (if any) about the benefits of widespread mask-wearing to curb the current pandemic (in specific contexts and combined with other measures, such as social distancing), the masks also expose how tightly this biological crisis is intertwined with politics. If anything, the cover portrait from the 16th century suggests that taking off the mask to reveal and access the allegedly true self is as problematic as claiming it could offer a new collective identity. While it might be a temporary necessity motivated by exceptional circumstances, the mask as a shared immunity machine exposes the challenges ahead. With or without it, societies still will need to find alternative ways to produce social synthesis that does not preclude the staging of differences.

• • •

References

- Al Jazeera News. 2020. “Which countries have made wearing face masks compulsory?,” June 3.

- Alloa, Emmanuel. 2011. Penser l’image. Dijon: Presses du réel.

- Aristotle. 1957. On the Soul; Parva Naturalia; On Breath. Translated by W. S Hett. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Arthur, Bruce. 2020. “We Say We’re All in This Together, but Are We?” thestar.com, April 29.

- Associated Press. 2020. “‘It’s The Invisible Enemy,’ Trump Says of Coronavirus.” The New York Times, March 18.

- Baader, Hannah. 1999. “Anonymous: ‘Sua cuique Persona’. Mask, role, portrait (ca. 1520).” In Geschichte der klassischen Bildgattungen in Quellentexten und Kommentaren: eine Buchreihe. Band 2. Porträt, edited by Rudolf Preimesberger, Hannah Baader, and Nicola Suthor. Berlin: Reimer.

- Baader, Hannah. 2000. “Eine persona sucht ihr Portrait. Unlesbarkeit des Gesichtes, Lesbarkeit der Maske im 16. Jahrhundert.” Gazzetta / ProLitteris : Literatur, beaux-arts, filosofia ; Organ der ProLitteris, Schweizerische Urheberrechtsgesellschaft für Literatur und Bildende Kunst, no. 2: 116–18.

- Baader, Hannah. 2015. Das Selbst im Anderen: Sprachen der Freundschaft und die Kunst des Porträts 1370-1520. Munich: Wilhelm Fink.

- Balko, Radley. 2013. Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Bascaramurty, Dakshana, Carly Weeks, and Eric Andrew-Gee. 2020. “New Data Show That Immigrants and Low-Income Earners Are More Susceptible to COVID-19,” The Globe and Mail, May 25.

- Barthes, Roland. 2007. Comment vivre ensemble : simulations romanesques de quelques espaces quotidiens ; notes de cours et de séminaires au Collège de France, 1976-1977. Paris : Seuil.

- Belting, Hans. 2017. Face and Mask: A Double History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bishara, Hakim. 2020. “A New IOS Shortcut Blurs Faces and Wipes Metadata for Protest Images.” Hyperallergic, June 5.

- Boehm, Gottfried, and W. J. T. Mitchell. 2009. “Pictorial versus Iconic Turn: Two Letters.” Culture, Theory and Critique 50, no. 2–3 (July 1): 103–21.

- Borum, Randy, and Chuck Tilby. 2005. “Anarchist Direct Actions: A Challenge for Law Enforcement.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28, no. 3 (May 1): 201–23.

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2003. “A Neglected Tradition? Art History as Bildwissenschaft.” Critical Inquiry 29, no. 3 (March 1): 418–28.

- Bullock, Katherine. 2020. “We Are All Niqabis Now: Coronavirus Masks Reveal Hypocrisy of Face Covering Bans.” The Conversation, April 27.

- Canales, Katie. 2020. “The Face Mask Is a Political Symbol in America, and What It Represents Has Changed Drastically in the 100 Years since the Last Major Pandemic.” Business Insider, May 29.

- Cineas, Fabiola. 2020. “Senators Are Demanding a Solution to Police Stopping Black Men for Wearing—and Not Wearing—Masks.” Vox, April 22.

- Courtine, Jean-Jacques, and Claudine Haroche. 2007. Histoire du visage. Paris: Payot.

- De La Garza, Alejandro. 2020. “For Black Men, Homemade Masks May Be a Risk All Their Own.” Time, April 16.

- De Lacy, Phillip H. 1977. “The Four Stoic ‘Personae.’” Illinois Classical Studies 2: 163–72.

- Dickson, E. J. 2020. “As the COVID-19 Pandemic Continues, Face Masks Have Become a Status Symbol.” Rolling Stone (blog), April 8.

- Dorn, Aaron van, Rebecca E. Cooney, and Miriam L. Sabin. 2020. “COVID-19 Exacerbating Inequalities in the US.” The Lancet 395, no. 10232 (April 18): 1243–44.

- Elden, Stuart. 2013. “V for Visibility.” Interstitial Journal, March.

- Esposito, Roberto. 2012a. The Third Person. Politics of Life and Philosophy of the Impersonal. Translated by Zakiya Hanafi. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Esposito, Roberto. 2012b. “The Dispositif of the Person.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 8, no. 1 (February 1): 17–30.

- Fischer, Matti. 2001. “Portrait and Mask, Signifiers of the Face in Classical Antiquity.” Assaph: Studies in Art History 6: 31–62.

- Fisher, Max, and Emma Bubola. 2020. “As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens Its Spread.” The New York Times, March 15, sec. World.

- Fossi, Gloria. 2009. Uffizi Gallery: Art, History, Collections. Firenze: Giunti Gruppo Editoriale.

- Friedersdorf, Conor. 2020. “Masks Are a Tool, Not a Symbol.” The Atlantic, May 5.

- Friedman, Vanessa. 2020. “The Mask.” The New York Times, March 17, sec. Style.

- Frontisi-Ducroux, Françoise. 2012. Du masque au visage: Aspects de l’identité en Grèce ancienne. Paris: Flammarion.

- Gaakeer, Jeanne. 2016. “‘Sua Cuique Persona?’ A Note on the Fiction of Legal Personhood and a Reflection on Interdisciplinary Consequences.” Law & Literature 28, no. 3 (September 1): 287–317.

- Gasché, Rodolphe. 2007. The Honor of Thinking: Critique, Theory, Philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ginaeselli, Matteo. 2017. “The Reverse of Giuliano Bugiardini’s ‘Portrait of a Lady’ in Paris.” The Burlington Magazine 159, no. 1370 (May): 360–63.

- Government of Canada. 2020. “Community-based measures to mitigate the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Canada.”

- Gunthert, André. 2020. L’image sociale.

- Heller-Roazen, Daniel. 2009. The Enemy of All Piracy and the Law of Nations. New York: Zone Books.

- Holert, Tom. 2020a. “Journal of Visual Culture & HaFI, 1,” Harun Farocki Institut.

- Holert, Tom. 2020b. “The weekend cover: L’Espresso, The Economist, Der Spiegel,” Harun Farocki Institut.

- Ildefonse, Frédérique. 2009. “La personne en Grèce ancienne.” Terrain. Anthropologie & sciences humaines, no. 52 (March 5): 64–77.

- Kane, Peter Lawrence. 2020. “The Anti-Mask League: Lockdown Protests Draw Parallels to 1918 Pandemic.” The Guardian, April 29, sec. World news.

- Kofman, Sarah. 1999. Camera Obscura: Of Ideology. Cornell University Press.

- Kohl, Jeanette, and Dominic Olariu, eds. 2012. En Face: Seven Essays on the Human Face. Marburg: Jonas.

- McFarling, Usha Lee. 2020. “Many Black Men Fear Wearing a Mask More than the Coronavirus.” STAT (blog), June 3.

- Meunier, Philippe, and Edgard Samper. 2013. Le Masque : Une “Inquiétante Étrangeté.” Saint-Étienne : Publications de l’Université de Saint-Etienne.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2017. The Appearance of Black Lives Matter. [NAME] Publications.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2020a. “Whiteness, Visuality and the Virus,” NicholasMirzoeff.com

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 1992. “The Pictorial Turn.” Artforum, March.

- Murphy, Margi, and James Titcomb. 2020. “Widespread Face Mask Use Could Make Facial Recognition Less Accurate.” The Telegraph, June 4.

- Nail, Thomas. 2014. “The Politics of the Mask.” HuffPost, January 23.

- Napier, A. David. 1986. Masks, Transformation, and Paradox. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Natali, Antonio. 1995. “La coperta della monaca.” In La piscina di Betsaida: Movimenti nell’arte fiorentina del Cinquecento. Firenze: Maschietto & Musolino, 116-37.

- Natali, Antonio, and Alessandro. Cecchi. 1996. L’Officina Della Maniera: Varietà e Fierezza Nell’arte Fiorentina Del Cinquecento Fra Le Due Repubbliche, 1494-1530. Firenze: Giunta regionale Toscana.

- Natali, Antonio. 2008. “Madonne fiorentine Raffaello, amico di Ridolfo.” In L’amore, l’arte e la grazia. Raffaello: la Madonna del Cardellino restaurata, edited by Marco Ciatti, Antonio Natali, and Patrizia Riitano, Firenze: Mandragora, 24–43.

- Natali, Antonio. 2015. “Les peintres florentins et Raphaël au début du XVIe siècle.” In Florence : Portraits À La Cour Des Médicis, edited by Carlo Falciani, Paris : Bruxelles: Mercator, 36-43.

- Nédoncelle, Maurice. 1948. “Prosopon et persona dans l’antiquité classique. Essai de bilan linguistique.” Revue des sciences religieuses 22, no. 3 : 277–99.

- Nunley, John Wallace, Cara MacCarty, John Emigh, and Lesley Ferris, eds. 1999. Masks: Faces of Culture. New York: H.N. Abrams.

- Olschanski, Reinhard. 2001. Maske und Person: zur Wirklichkeit des Darstellens und Verhüllens. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Pelletier, Francine. 2020. “Le masque.” Le Devoir, May 13.

- Quintilian. 1921. The Institutio oratoria. Translated by Harold Edgeworth Butler. Vol. 2. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

- Riisgaard, Lone, and Bjørn Thomassen. 2016. “Powers of the Mask: Political Subjectivation and Rites of Participation in Local-Global Protest:” Theory, Culture & Society, July 13.

- Rodowick, David Norman. 2014. Elegy for Theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Rojas, Rick. 2020. “Masks Become a Flash Point in the Virus Culture Wars.” The New York Times, May 3, sec. U.S.

- Ruiz, Pollyanna. 2017. “Power Revealed: Masking Police Officers in the Public Sphere.” Visual Communication 16, no. 3 (August 1): 299–314.

- Sayej, Nadja. 2020. “Words at the window: how people are connecting with hopeful messages,” The Guardian.

- Schulz, Martin. 2013. “The Unmasking of Images: The Anachronism of TV-Faces.” In Imagery in the 21st Century, edited by Oliver Grau and Thomas Veigl, 37–56.

- Stott, Clifford, Marcus Beale, Geoff Pearson, Jonas Rees, Jonas Havelund, Alain Brechbühl, Ed McGuire, and Megan Oakley. 2019. “International Norms: Governing Police Identification & the Wearing of Masks During Protest: Two Rapid Evidence Reviews.” Keele Policing Academic Collaboration (KPAC).

- Sealy, Thomas. 2020. “Is There a Difference between a Niqab and a Face Mask?” openDemocracy, May 6.

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. 1935. Moral Essays. Translated by John W Basore. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Serraino, Tatyana Kalaydjian. 2019. “The Unseeing Masks: The Meaning of the Two Masks in Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Venus and Cupid of 1532–1534.” Master of Arts in Art History, John Cabot University.

- Shepherd, Katie. 2020. “Masks Become a Flash Point for Protests and Fights as Businesses, Beaches and Parks Reopen.” Washington Post, May 5.

- Spinelli, Riccardo. 2018. “La Monaca degli Uffizi, una vedova di casa rinieri e il suo autore: Giuliano Bugiardini o Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio?” In Tra archivi e storia: scritti dedicati ad Alessandra Contini Bonacossi, edited by Elisabetta Insabato, Rosalia Manno Tolu, Ernestina Pellegrini, Anna Scattigno, and Alessandra Contini. Firenze: Firenze University Press, 91–100.

- Spinoza, B. de. 1889. The Chief Works of Benedict de Spinoza: De Intellectus Emendatione. Ethica. Correspondence. (Abridged). Translated by R.H.W. Elwes. London: George Bell And Sons.

- Stimilli, Davide. 2012. The Face of Immortality: Physiognomy and Criticism. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Stoppard, Lou. 2020. “Will Mandatory Face Masks End the Burqa Bans?” The New York Times, May 19, sec. Style.

- Taylor, Derrick Bryson. 2020. “For Black Men, Fear That Masks Will Invite Racial Profiling.” The New York Times, April 14, sec. U.S.

- Theophanidis, Philippe. 2018. “François Laruelle and (Non-Standard) Communication.” Moment Journal 5, no. 1 (June 15).

- Tiqqun.2012. Theory of Bloom. Translated by Robert Hurley. Berkeley: LBC Books.

- Unni, Krishnan P. 2020. “The Mask Is the Cultural Icon of the Pandemic.” The Indian Express (blog), June 1.

- Valiante, Giuseppe. 2020. “Montreal suburb of Cote St-Luc becomes first municipality in Canada to make masks mandatory,” CTV News Montreal.

- Vernant, Jean Pierre. 1990. Figures, idoles, masques. Paris: Julliard.

- Weihe, Richard. 2004. Die Paradoxie der Maske: Geschichte einer Form. Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

- Werly, Richard. 2020. “Emmanuel Macron: «Nous sommes en guerre face à un ennemi invisible».” Le Temps, March 16.

- World Health Organization. 2020. “Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19,” Interim Guidance, June 5.

• • •

1. On the relationship between the word “theory” and the faculty of vision, see the philological explanation provided by Martin Heidegger in his August 1954 lecture titled, “Science and Reflection” (1977, 163–64). For a broader discussion on the meaning of “theory,” see also Gasché (2007, 147–68) and Rodowick (2014, 7–13). ↩︎︎

2. For an introduction to the “pictorial turn,” see Mitchell (1992). For a discussion about the difference between the American and German traditions, see Bredekamp (2003), Boehm and Mitchell (2009) and Alloa (2011).↩︎︎

3. The relationship between images and the capacity to think is put forward in Aristotle’s On the Soul: “Hence the soul never thinks without a mental image” (1957, 177).↩︎︎

4. In addition to its joint initiative with the Journal of Visual Culture, the Harun Farocki Institut also offers collections of cover pages from various media (Holert, 2020b). See also Mirzoeff (2020). On his blog L’image sociale, French historian of visual culture André Gunthert offers several analyses examining the ways the pandemic is made visible to us (2020). Other initiatives merely collect images, such as the website duetocovid19.com, which documents “the temporary signs that have gone up across our communities” in 118 cities across the world. Similarly, photographer Stephen Lovekin documented messages displayed in the windows of his Brooklyn neighborhood during quarantine (Sayej, 2020).↩︎︎

5. See, for example, quotes from U.S. President Donald Trump: “It’s the invisible enemy” (Associated Press, 2020), and French President Emmanuel Macron: “Nous sommes en guerre face à un ennemi invisible” (Werly, 2020). ↩︎︎

6. See, for instance, “Community-based measures to mitigate the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Canada” (Gov. of Canada, 2020). ↩︎︎

7. At the time of writing [June 16th, 2020], more than 50 countries have made wearing face masks compulsory (Al Jazeera News, 2020). In Canada on June 2, 2020, the Montreal suburb of Côte Saint-Luc became the first municipality in the country to make masks mandatory in public buildings (Valiante 2020). On June 5, 2020, the World Health Organization updated its guidance, advising governments to encourage “the general public to wear masks in specific situations and settings” (2020, 6).↩︎︎

8. Among many important studies on the topic of mask, face and person see Belting (2017), Courtine and Haroche (2007), Frontisi-Ducroux (2012), Kohl and Olariu (2012), Meunier and Semper (2013), Napier (1986), Nunley et al. (1999), Olschanski (2001), Vernant (1990) and Weihe (2004). ↩︎︎

9. Elsewhere, it is worth exploring the many problems arising from any attempt to study of what is immediately present for us: in this case, a global, ongoing pandemic. These “rapid response” research initiatives we are witnessing— this contribution included—raise a number of difficult issues. Certainly they are, or at least they aim to be, timely. However, if—as Roland Barthes once suggested—the contemporary is untimely, there may be value in departing from the present, if only to get back to it better later on (2007, 36). ↩︎︎

10. Inv. 1890, no. 6042. The painting is sometimes instead attributed to Giuliano Bugiardini, while more recent scholarship attributes it to Mariotto Albertinelli. Two main sources provide detailed commentaries on the painting: Antonio Natali, Director of the Uffizi Gallery from 2006 to 2015 (see 1995; 2008; 2015; Natali and Cecchi 2016, 123–35), and Hannah Baader, Permanent Senior Research Scholar at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence (see 1999; 2000, 116–18; 2015, 271–96). Additional observations are found in Belting (2011, 77–79; 2017, 94–96), Gaakeer (2016), Gianeselli (2017), Fossi (2009), Schulz (2013, 46–47), Spinelli (2018), and Serraino (2019). ↩︎︎

11. Although no direct literary source has been determined for certain, art historians have observed that a similar expression can be found in Seneca’s De beneficiis: “Adspicienda ergo non minus sua cuique persona est quam eius, de quo iuvando quis cogitate” (Book II, §17.2; see 1935, 83) and in Quintilian’s Institutiones: “Illae firmiores ex sua cuique persona probationes, quae credibilem rationem subiectam habeant” (Book V, §12.13; see 1921, 304). ↩︎︎

12. For an overview of the discussion about the attribution of this portrait, see Gianeselli (2017, 360n9). ↩︎︎

13. Inv. 1890, no. 8380. ↩︎︎

14. The important relationship between masks and death cannot be explored here. See Belting (2017, 77–90) and Serraino (2019, 38–44). ↩︎︎

15. It is worth noting the painting can fool at least one gaze: that of the machine. Pointing a smartphone camera at it will trigger the facial recognition system: the camera identifies the mask as a face. ↩︎︎

16. It has been suggested the mask is genderless (as it does not appear to be predicated with gender markers) and generic (it is not a specific face, but could be anyone; Baader 1999, 239). While it may well be genderless, it is problematic to suggest that it stands for a generic human face. It is generic only within the specific realm of white, European art. In other words, it does not represent a human face in general, but a white face. ↩︎︎

17. The idea that truth might be opposed, but in no way separated from what is false is found, among many others, in Spinoza: “For the truth is the index of itself and of what is false” (1889, 417). From this perspective, the false takes place with the truth, and not independently from it. For further considerations on Spinoza’s remark, see Theophanidis (2018). ↩︎︎

18. This what allows Davide Stimilli to summarize succinctly: “A face is no body, personne” (2012, 2). ↩︎︎

19. This inversion is an analog to how the meaning of camera obscura changed, first being associated with exactitude and a faithful representation of reality, only to later become an exemplary metaphor for ideology and the masking of truth (Kofman 1999, 1–7; Mitchell 1986, 160–208). ↩︎︎

20. In recent years there have been numerous efforts to try and think past the traditional paradigm of modern politics. These have gone in various directions, from “micro-politics” to “post-politics,” all the way through the ideas of “apolitics”, “unpolical”, “infrapolitics,” and others. ↩︎︎

21. On the politics of masks as they relate to recent protest movements, see Elden (2013), Nail (2013), and Riisgaard and Thomassen (2016). Giorgio Agamben clearly illustrates how singularities without identity—what he calls “whatever singularities”—present a threat to the status quo of the modern State paradigm (1993, 85–87). ↩︎︎

22. One example is the ObscuraCam developed by the Guardian Project. Regarding the issue of visibility as it intersects with the Black Lives Matter movements, see Mirzoeff (2017).↩︎︎

23. This is not the first time a portion of the population has fought for the right not to wear mask during a pandemic: the 1918 pandemic also saw the rise of an “Anti-Mask League” (Kane 2020). ↩︎︎

24. The militarization of police forces has been widely documented in the past 20 years. See, among others, Balko (2013). ↩︎︎

25. On the legal issue of police officers masking themselves, see the thoroughly documented reviews by Scott et al. (2019) and Ruiz (2017). The topic of how wearing masks in public has been dealt with from a legal perspective has a long and complicated history that cannot be covered here. ↩︎︎

26. The photo was uploaded to Dai Sugano’s Instagram account on May 30, 2020. Getty owns the license. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Technology

- Tagged: biopolitics, covid, face, mask, person, politics