An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

“I’ll think about that later. Right now I still wanted to tell you that between those who have a love of life and those who have lost it no common language exists. The same event is described by the two in two totally different ways: one derives joy and the other torment, each extracting from it confirmation of its own worldview.”

“Both of them can’t be right.”

“No. Generally speaking, as you know, and one must have the courage to say so, the others are right.”

“The lemmings?”

“Sure, let’s call them the lemmings.”

“And us?”

“We’re wrong, and we know it, but we find it more palatable to keep our eyes shut. Life does not have a purpose; pain always prevails over joy; we are all condemned to death, and the day of execution is not revealed; we are condemned to witness the death of those closest to us. There are compensations, but few. We know all this, and yet something protects us and sustains us and keeps us from devastation. What is this protection? Perhaps it is only habit: the habit of living, which we contract at birth.”

☛ Primo Levi, “Heading West,” trans. Jenny McPhee, collected in The Complete Works of Primo Levi, New York: Liveright Publishing, 2015, pp. 586-595, PDF.

The short story “Heading West” was first published in Italian under the titled “Verso occidente,” as part of the collection Vizio di forma (Giulio Einaudi, 1971, PDF; the same short story was later republished in the 1987 second edition of Vizio di forma, as well as in two subsequent different collections: see the entry at the Catalogo Vegetti della Letteratura Fantastica). Prior to its inclusion in The Complete Works of Primo Levi, it first appeared in English under the title “Westward” in a translation by Raymond Rosenthal, as part of the collection The Sixth Day and Other Tales (New York: Summit Books, 1990, pp. 126-135, PDF).

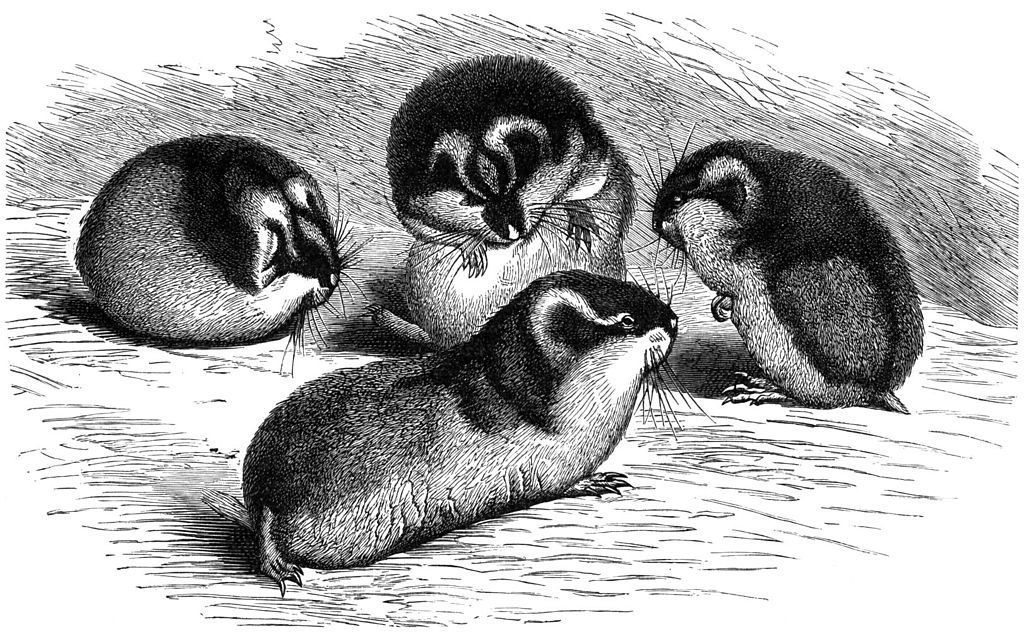

The short story, merely half a dozen pages long, was written between 1967 and 1970, alongside 19 others short stories, all gathered in Vizio di forma (which translates into Flaw of Form, in English). It tells the story of two (presumed) scientists, Anna and Walter, as they observe and try to understand the behaviour of an “army of lemmings.” The small rodents make their way toward a beach and enter the water, only to drown or to be devoured by birds circling above. While the idea of lemmings inexplicably committing mass suicide is now considered a myth by the scientific community, it informes Levi’s short story through and through. Anna and Walter work hard to eliminate possible explanations for the phenomena. It is neither hunger nor overpopulation that drives the lemmings, they contend, but something more fundamental. The lemmings, Walter suggests, “actually want to die.” The pair decides to further investigate the situation in order to pinpoint the source of this dreadful behaviour. They wish to understand why these lemmings have lost the desire to live. The ultimate goal would be to synthetise a “hormone that inhibits existential emptiness.” Anna, for one, is uncertain about the value of such a “solution.”

While tests are being conducted, Walter and Anna make a trip to the Amazon river to visit an indigenous tribe known as the Arunde. The reason for their visit quickly becomes clear: the Arunde population has been experiencing a steady decline due to nothing else than “an inordinate number of suicides.” The village elder calmly explains that the Arunde “never held metaphysical convictions.” Furthermore, the Arunde “attributed little value to the survival of the individual, and none to the national survival.” Walter and Anna are told that suicide is an integral part of the Arunde’s way of life.

Upon returning to the ground where they are conducting their experiments with the lemmings, the two scientists learned that an hormone was indeed succesfully synthesized. Named “Factor L,” the hormone restores “the will to live.” It was subsequently detected in normal, healthy blood. However, it is discovered that the substance is absent from the blood of lemmings. Furthermore, Walter establishes that the substance is also absent from the blood of the Arunde. Walter first send a package of the substance to the Arunde, hoping to help them overcome their suicidal inclination. Not wanting to wait for their reply, he then proceeds to try to inoculate the lemmings by converting the substance into a gas. However, while standing in their path, he is quickly engulfed by the sheer size of the swarm. In the end, he can neither alter the course of the lemmings, nor escape death himself, which Anna witnesses from afar.

The short story ends with Anna receiving the package Walter had sent to the Arunde. It had been sent back with the following note:

“The Arunde people, soon no longer a people, send their regards and thank you. We do not wish to offend, but we are returning your medicine, so that those among you who might want to can profit from it. We prefer freedom to drugs and death to illusion.”

The Complete Works of Primo Levi provides some useful indications about the publication of the collection Vizio di forma. In an accompanying note, Domenico Scarpa offers a quick overview of the political situation in Italy, at the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies:

For Italy these were years of upheaval in society, in the economy, in politics, in public morality. “Sessantotto”—a date, 1968, written in letters—was the year of the student protests, while 1969 was marked by the union struggles of the so-called hot autumn and, just a little later, on December 12, in Milan, by a neo-Fascist act of terrorism: a bomb went off in a bank, leaving seventeen dead and eighty-eight wounded. Fears of a reactionary coup were widespread, and a period of extreme political tension began: what came to be called the “years of lead.”

Scarpa also offers an English translation of the text appearing on the jacket copy of the first edition from 1971. Scarpa hypothesises that while the text on the jacket is not signed, it was likely written by Primo Levi. It is worth noting how the text refuses to frame the collection as being solely pessimistic:

Will there be historians in the future—even, let’s say, in the next century? It’s not at all certain: mankind may have lost any interest in the past, preoccupied as it will surely be in sorting out the tangle of the future; or it may have lost the taste for works of the spirit in general, being focused uniquely on survival; or it may have ceased to exist. But, if there are historians, they will not devote much time to the Punic Wars, or the Crusades, or Waterloo, but will instead concentrate on this twentieth century, and, more specifically, the decade that has just begun.

It will be a unique decade. In the space of a few years, almost overnight, we’ve realized that something conclusive has happened, or is about to happen: like someone who, navigating on a calm river, suddenly observes that the banks are retreating backward, the water teeming with whirlpools, and hears the thunder of waterfalls close by. There is no indicator that is not soaring upward: the world population, DDT in the fat of penguins, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, lead in our veins. While half the world is still waiting for the benefits of technology, the other half has touched lunar soil and is poisoned by the garbage that has accumulated in a decade: but there is no choice, we cannot return to Arcadia; by technology, and by that alone, can the planetary order be restored, the “flaw of form” repaired. Before the urgency of these problems, the political questions pale. This is the climate in which, literally or in spirit, the twenty stories by Primo Levi presented here take place. Beyond the veil of irony, it is close to that of his preceding books: we breathe an air of sadness but not hopelessness, of distrust in the present and, at the same time, considerable confidence in the future: man the maker of himself, inventor and unique possessor of reason, will be able to stop in time on his path “heading west.”

This commitment to acknowledge the dire historical situation while refusing to settle into a pessimistic and moribond mood is even further emphasized. While Scarpa indicates that the collection was initially to be titled Anti-Humanism, he also notes how Levi refused to succumb to sheer despair:

Levi declared that he was opposed to despair, which “is surely irrational: it resolves no problems, creates new ones, and is by its nature painful.” He continued, rather, to claim a “faith that I would call biological, that saturates every living fiber,” but at the same time he said of the language of his new stories that it is “a language that I feel is ironic, and that I perceive as strident, awry, spiteful, deliberately anti-poetic.”

Sixteen years later, in January 1987, Primo Levi wrote a letter to the editor Giulio Einaudi to accompany the second edition of the collection Vizio di forma. Simply titled “Lettera 1987” the letter once more comments on and provides nuance for the pessimistic visions expressed in the collection. The first part of the letter is reproduced below:

Dear Editor,

Your proposal to reprint Flaw of Form more than fifteen years after it was first published both saddens and cheers me. How can two such contradictory states of being exist together? I shall try to explain it both to you and to myself.

It saddens me because these are stories related to a time that was much sadder than the present, for Italy, for the world, and also for me. They are linked to an apocalyptic, pessimistic, and defeatist vision, the same one that inspired Roberto Vacca’s The Coming Dark Age. But the new Dark Age has not come: things haven’t fallen apart, and instead there are tentative signs of a world order based, if not on mutual respect, at least on mutual fear. Despite the terrorizing, if slumbering, arsenals, the fear of the “Dissipatio Humani Generis” (Guido Morselli), whether rightly or wrongly, has been subjectively attenuated. How things actually are, no one knows.

It’s worth noting that Primo Levi wrote this letter merely four month before his death, on April 11, 1987. While the death was originally ruled as a suicide (and considered as such by some of his biographers), more recent accounts lean toward an accidental death. See for instance the accounts by Diego Gambetta (“Primo Levi’s Last Moments” June 1, 1999) and Carlin Romano (“Primo Levi’s Work Outshines His Murky Death” Nov.-Dec. 2019).

On July 28, 2021, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben borrows from Primo Levi’s short story in one of his interventions regarding the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (see previously here). Titled “Uomini e lemmings,” the short comment suggests that human beings themselves might soon lost the will to live and, consequently, might be heading toward extension (or, in Levi’s own words, might be “heading west”)1. Agamben –leaning into the myth of lemmings committing mass suicide– makes no mention of the fact that similar (although not identical) diagnostics have been made throughout the 20th century by a number of authors (in no insignificant part driven by the explosion of two atomic bombs over Japan in 1945). Recall the last observations shared by Sigmund Freud in Civilization and its Discontent, first published in 1930:

The fateful question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and self-destruction. It may be that in this respect precisely the present time deserves a special interest. Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in exterminating one another to the last man. They know this, and hence comes a large part of their current unrest, their unhappiness and their mood of anxiety. (tr. by James Strachey, New York: W.W. Norton&Company Inc., [1930] 1962, p. 92)

Prior to Civilization and its Discontent, Freud had borrowed from Sabina Spielrein’s theory about the intimate relation between destruction and life to develop his concept of Todestrieb or “death drive,” which was first laid out in 1920, in his book Jenseits des Lustprinzips (Beyond the Pleasure Principle). On the topic of madness and suicide, see previously here “On Madness” or “On Insanity” by Leo Tolstoy, 1910.

In 1958, science-fiction author Richard Matheson published a very short story titled “Lemmings”. It appears in the January issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (pp. 117-118, PDF; the entire issue is available here; the short story “Lemmings” was also collected in Steel and Other Stories, Tor, 2011, pp. 233-236). Richard Matheson is best known for his 1954 novel I Am Legend and for his 1956 novel The Shrinking Man. In his short story, Matheson also borrows from the myth of lemmings committing mass suicide in order to comment on the capacity for humans to self-annihiliate. In her essay “Who Killed All the Humans,” Amy S. Jorgensen offers the following interpretation:

Instead of nuclear bombs annihilating the world’s population as one might expect, the end of the human race comes from mass suicides affecting the entire population over the course of a week. In a real sense, the story’s human population is the source of its own destruction. In the real world, humans had created hydrogen bombs capable of killing millions and possessed the power to launch the bombs’ destructive capabilities. The mass suicide of the humans in “Lemmings,” therefore, serves as a metaphor for the massive destruction brought about by human hands.” (in Reading Richard Matheson: A Critical Survey, ed. by Cheyenne Mathews and Janet V. Haedicke, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, pp. 75-76).

Also interesting to explore are the possible parallels between Primo Levi’s short story and a short story published by Agamben in 1964: “Decadenza”. Both “Decadenza” and “Verso occidente” were written by Italian authors during a period of great political upheaval in Italy. Both titles evoke the idea of “decline” (“occidente” being from occidere, meaning “fall down, go down”: indeed, the place where the sun goes to set and to disappear). Finally –although this is not by any mean an exhaustive account of their points of contact, nor of their differences– both are science fiction fables centred on animal populations facing inexplicable extinction.

• • •

1.There is one other mention of lemmings in Agamben’s opus, although indirect. In Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, Agamben uses the following quote from Gitta Sereny’s book Into That Darkness: An Examination of Conscience (New York: Random House, [1974]1983):

“They were so weak; they let themselves do anything. They were people with whom there was no common ground, no possibility of communication — this is where the contempt came from. I just couldn’t imagine how they could give in like that. Recently I read a book on winter rabbits, who every five or six years throw themselves into the sea to die; it made me think of Treblinka”

In the 1983 edition of Sereny’s book quoted by Agamben, this excerpt appears on page 313. In the English edition of Remnants of Auschwitz the quote can be found on pages 78-79. Worth noting how Daniel Heller-Roazen uses “winter rabbits” instead of “lemmings”. He is likely following the Italian edition Quel che resta Auschwitz (1998) where “conigli delle nevi” is used, most likely because Agamben is referring to the Italian translation of Sereny’s book In Tuelle tenebre (Milano: Adelphi 1994). If one were to examine the English edition from 1983, the quote reads as follow. It is also very important to note that the quote does not come from Sereny herself, but is rather attributed to Franz Stangl, a Kommandant of the Nazi extermination camps Sobibor and Treblinka, whom Sereny was interviewing:

“It has nothing to do with hate. They were so weak; they allowed everything to happen – to be done to them. They were people with whom there was no common ground, no possibility of communication – that is how contempt is born. I could never understand how they could just give in as they did. Quite recently I read a book about lemmings, who every five or six years just wander into the sea and die; that made me think of Treblinka.” (New York: Random House, [1974]1983, pp. 233) ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: Agamben, death, lemmings, Literature, Primo Levi