An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

It is an analogous, and probably conscious, sense of discomfort that led Jacques Derrida to choose as a leitmotif for his book on friendship a sibylline motto, attributed to Aristotle by tradition, that negates friendship with the very same gesture by which it seems to invoke it: o philoi, oudeis philos, “O friends, there are no friends.” […] It can be found in Montaigne and in Nietzsche, both of whom would have taken it from Diogenes Laertius. But if we open a modern edition of the latter’s Lives of Eminent Philosophers to the chapter dedicated to Aristotle’s biography (5.21), we do not find the phrase in question but rather one to all appearances almost identical, whose significance is nevertheless different and much less mysterious: ōi (omega with iota subscript) philoi, oudeis philos, “He who has (many) friends, does not have a single friend.”

A visit to the library was all it took to clarify the mystery.

☛ “The Friend” in What Is an Apparatus?, by Giorgio Agamben, tr. by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, Stanford: Stanford University Press, [2004]2009, pp. 26-27.

Agamben’s essay was first published in an English translation by Joseph Falsone under the title “Friendship” in issue 5 of the journal Contretemps, in December 2004 (pp. 2-7; PDF). It was first published in Italian under the title L’Amico in 2007 (Nottetempo). The French translation by Martin Rueff was published the same year as L’amitié (Paris: Payor & Rivages).

For some reason, the French edition has L’Amicizia as the original Italian. I find the English translation to be more reliable, especially for the matter at hand here. The French translation completely omits Agamben’s observation regarding the “omega with iota subscript”: it has been cropped out.

• • •

• Introduction

Although it has been and still is often attributed to Aristotle, the quote “O friends, there are no friends” does not appear in the the Corpus Aristotelicum (the collection of Aristotle’s work). Up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was instead found in Diogenes Laertius’s Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. The quote gained some notoriety as it was used by Montaigne (1588), Kant (1797), and Nietzsche (1878). In recent years, it became more widely known as it was used and commented by Jacques Derrida in his book Politiques de l’amitié (1994).

That quote, however, is the result of a transcription issue, something Derrida was aware of. The issue was identified as early as the twelfth century. However, it was more thoroughly commented upon by classical philologist Isaac Casaubon in a series of observations regarding Diogenes Laertius’s Lives published anonymously in 1583. The problematic quote nonetheless remained unchanged in subsequent editions, until the text was finally modified in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Since then, the form “O friends, there are no friends” is not to be found in modern editions of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives. Instead, one finds the following quote (in some variations): “He who has many friends, does not have friends”.

The following analysis documents how the quote “O friends, there are no friends” was used by renowned authors, where and when it originates exactly in Diogenes Laertius’s Lives, and just how it came to be considered apocryphal and replaced by the modern version “He who has many friends, does not have friends”.

More specifically, I document how the apocryphal quote was used by Montaigne, Kant and Nietzsche. I then locate it in the oldest continuous manuscript of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives still in existence, as well as in subsequent manuscripts and printed editions. I show how at the end of the sixteenth century, the quote was corrected by classical scholar Isaac Casaubon and others, and how it was ultimately modified in nineteenth century printed editions of the Lives. In the conclusion, I briefly return to both Jacques Derrida’s and Giorgio Agamben’s accounts of the issue.

This analysis is not meant to be a record of everything that has been said about this issue. Nor does it pretend to be definitive –far from it–, or to settle things once and for all. The comments I have to offer are provisional. They are meant to feed a discussion that started more than four hundred years ago –among a few friends of λόγος, I am tempted to add– and that is still going today.

The main novelty of this contribution lies in the access it offers to digitized copies of most of the documents at the center of this discussion. When he first wrote his essay back in 2004, Agamben still needed a short stroll to the library in order to solve the “mystery” surrounding the apocryphal quote: “Una visita in biblioteca fu sufficiente a chiarire il mistero”. A couple of years later –thanks in part to the Google Books initiative– anyone with an internet connexion can scroll through digitized copies of the original documents hosted online: both manuscripts and printed editions.

Besides, Agamben’s solution to what he calls “il mistero” had in fact been quite precisely documented more than a decade earlier. The existence of Isaac Casaubon’s observation and its meaning had been carefully examined by Ullrich Langer in his book Perfect Friendship: Studies in Literature and Moral Philosophy from Boccaccio to Corneille published in 1994 (see especially pages 18-20).

That being said, where most previous arguments have solely relied on bibliographical notations (at the notable exception of Pierre Wechter’s self-published philological comment: see below), this analysis provides a visual account of the relevant references. It raises new observations, and brings some clarification to Agamben’s account of Isaac Casaubon’s contribution to the story.

I would like to thank the following individuals who provided me with valuable help during my research, especially in regard with Greek diacritics: Professor Olav Eikeland, Twitter user @totiesti and Professor Jacques Bouchard. Aside from Ullrich Langer’s remarks, Pierre Wechter’s document Trois citations «à statut particulier» (2010) was by far the most useful I found. I’m thankful to him for providing me with an updated version of his research, as well as providing me with a transcription and a translation of Piero Vettori’s short comment. Finally, I am grateful to Professor Tiziano Dorandi for the time he took to answer some of my questions regarding ancient manuscripts of the Lives. I remain, of course, solely responsible for the mistakes or inexactitudes that may have nonetheless found their way in my analysis.

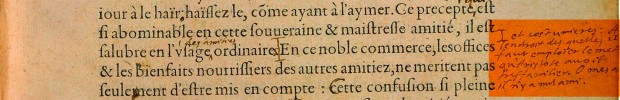

• Montaigne

In the Essais, the quote was added by hand in the right margin of page 72 (JPG) of the Bordeaux Copy from 1588, in the chap. XXVIII on friendship: “De l’Amitié”. The hand written note reads as follows (I borrow the transcription from Pierre Wechter):

A l’endroit des quelles il faut emploïer le mot qu’Aristote auoit treſfamilier. O mes a[mis] il n’y a nul ami.

In Florio’s English translation of Montaigne’s Essays, first published in 1603, the chapter “On Friendship” is no. XXVII (instead of XXVIII) and the quote is translated, with more liberties, as follows: “Oh ye friends, there is no perfect friend.”

Another English translation, more literal, was done by Donald M. Frame. It was first published in 1957 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, [1957] 1958, p. 140):

![Montaigne’s Essays, tr. by Donald M. Frame, Stanford: Stanford University Press, [1957] 1958, p. 140](https://aphelis.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MONTAIGNE_1588_English_tr_Frame_1957_Essays_p140-620x154.jpg)

• Kant

Although Agamben does not mention him, Kant also used the apocryphal version of the quote found in Diogenes Laertius’s Lives. It appears in The Metaphysics of Morals (Die Metaphysik der Sitten, 1797), which is not to be confused with the earlier Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785). In the second volume titled the “Doctrine of Virtue” (Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Tugendlehre) it is found in I, Part II, Chap. II, §46, where Kant discusses the “Ethical Duties of Men toward One Another with Regard to Their Condition”, and tackles the topic of friendship in particular. From the English translation by Mary Gregor:

Friendship thought as attainable in its purity or completeness (between Orestes and Pylades, Theseus and Pirithous) is the hobby horse of writers of romances. On the other hand Aristotle says: My dear friend, there is no such thing as a friend! The following remarks may draw attention to the difficulties in perfect friendship. (Cambridge: Cambridge Univesity Press, 1991, p. 262).

Here is the same excerpt, this time from the first German edition (Königsberg, 1797, p. 153):

Kant used the same quote a year later in his Anthropology From a Pragmatic Point of View (Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht abgefasst, 1798). The quote appears on page 44 in this edition from 1800:

![Immanuel Kant, ‘Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht abgefasst’, [1798]1800, p. 44](https://aphelis.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/KANT_1798_Anthropologie_in_pragmatischer_Hinsicht_abgefasst_p44-620x325.jpg)

In a modern edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), translator Robert B. Louden was well aware of the problem, and added the following note:

Kant repeats this (mis)quotation in several other versions of his anthropology lectures – e.g., Collins 25: 106, Parov 25-330, Menschenkunde 25:933 (p. 44, note 42) (p. 44)

• Nietzsche

Nietzsche mentions the same quote –“O friends, there are no friends”– in Human, All Too Human. Although the book was first published in 1878, the relevant part on friendship was added later, in an augmented edition published by Nietzsche in two volumes. In this edition by E.W. Fritzsch (Leipzig, 1886), it appears in Vol. I, §376, p. 290:

The original German version can also be found at Nietzsche Source, in the Digital Critical Edition section: eKGWB/MA-376. The section that is of interest to the present matter is the following (it is followed with an English translation by Marion Faber from 1984):

„Freunde, es giebt keine Freunde!“ so rief der sterbende Weise;

„Feinde, es giebt keinen Feind!“ — ruf’ ich, der lebende Thor.

“Friends, there are no friends!” the dying wise man shouted.

“Enemies, there is no enemy!” shout I, the living fool.

• Diogenes Laertius

As I mentioned earlier, it is well established that the quote used in all those cases does not come from the Corpus Aristotelicum. Instead, it comes from Diogenes Laertius’s account of Aristotle’s life and ideas in his famous Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. The quote is –or rather used to be– found in Book V, §21.

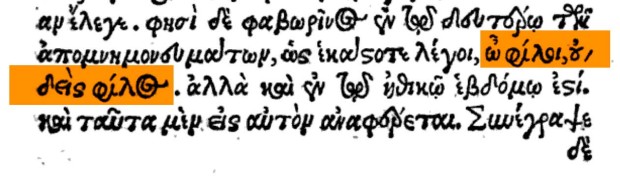

The problem, as pointed out by Agamben, is that if one was to look for this specific reference in a modern edition of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives, the quote wouldn’t show. This can be easily verified by searching the online edition of R.D. Hicks’s translation (Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library, 1925; the digital edition corresponds to the later edition of 1972). In Book V, §21, we find this passage:

Favorinus in the second book of his Memorabilia mentions as one of his habitual sayings that “He who has friends can have no true friend.” Further, this is found in the seventh book of the Ethics. (read it at Perseus)

φησὶ δὲ Φαβωρῖνος ἐν τῷ δευτέρῳ τῶν Ἀπομνημονευμάτων ὡς ἑκάστοτε λέγοι, “ᾧ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος”: ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐν τῷ ἑβδόμῳ τῶν Ἠθικῶν ἐστι. (D.L. 5.1.21)

In the Greek version of this edition, the quote attributed to Aristotle reads as follows: “ᾧ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος”.

How is it that “O friends, there are no friends” somehow got transformed into “He who has friends can have no true friend”? In order to fully understand what happened, one has to journey from copies to copies to the earliest editions of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives.

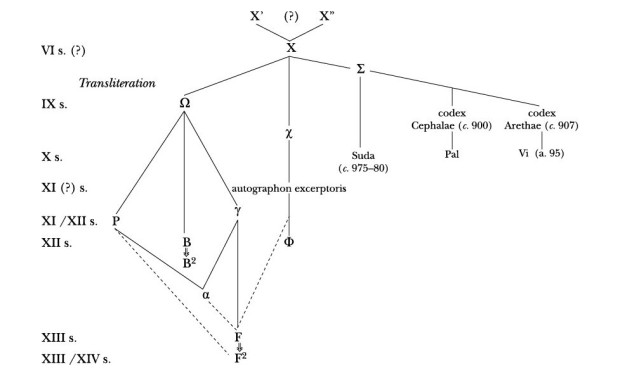

A short overview of the history of Diogenes Laertius’s text provides a useful starting point. For this, I have relied on the newest critical edition of the Lives of Eminent Philosophers edited by Tiziano Dorandi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). I have provided online access to digitized copies of the relevant documents whenever I was able to locate them, as well as images of the excerpts being discussed. Most images can be enlarged. Tiziano Dorandi kindly helped me to properly identify the manuscript hosted at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The Lives is a collection of ten books about the lives and ideas of various philosophers. It is believed to have been written in the first decades of the third century AD. The original document did not survive, but manuscript reproductions did, entirely or partially. The oldest still existing today was made during the tenth century: it is a collection of excerpts dated from July 28, 925. The oldest continuous manuscripts (that is not a collection of fragments, or a separate chapter) date back to the eleventh century. Some four hundred years later, editors relied on those documents to produce the first printed editions of the Lives of Eminent Philosophers. It is through this long series of various manuscripts and printed editions, copied and recopied, transliterated and translated, that Diogenes Laertius’s text ultimately reached modern times.

Reproductions of selected pages from Italian manuscripts dating from the fifteenth century can be found online at Bodleian Libraries (Oxford University). As we will see in a moment, digitized copies of continuous manuscripts are available as well.

The Bibliothèque Nationale de France is hosting a digital copy of a continuous Greek manuscript of particular interest. Access to the entire document is possible through Gallica. The first words of the excerpt reproduced below read: Λαερτίου Διογένους Βίοι καὶ γνῶμαι τῶν ἐν φιλοσοφίᾳ εὐδοκιμησάντων.

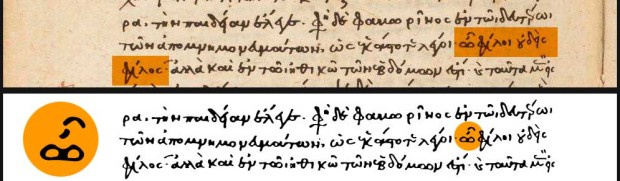

This is not just any manuscript: it is the codex Parisinus, known as manuscript (or MS) P (Gr. 1759). BNF records have it produced during the thirteenth century, and so has R.D. Hicks in the Loeb edition of the Lives published in 1925. However, Tiziano Dorandi assured me that this is more certainly erroneous: the manuscript was produced earlier, somewhere in the eleventh or twelfth century.

MS P is in fact one of the three oldest continuous manuscripts still in existence today, the two others being B (codex Neapolitanus Burbonicus III B 29 –sometimes spelled Borbonicus–, from the twelfth century) and F (Laurentianus 69.13, from the thirteenth century). It has been long established that B is a manuscript copy of superior quality, while P and F are contaminated by revisions:

P, though contemporary with (or slightly earlier than) B and also derived from Ω, has less pure text because it had already been deliberately altered. (Dorandi, 2013: “Principles and arrangements of this edition”; see also in his Laertiana, 2009: p. 51)

The reason why MS B is less contaminated by revisions and conjectures is well worth musing upon. The scribe who copied it from an even older manuscript (Ω) had very little knowledge of Greek:

[the scribe] had great difficulty transcribing his model and limited himself to reproducing it in a mechanical way exactly as he managed to decipher it; at times, he did not even understand the meaning of the text that he was writing. (Dorandi, 2013: “New evidence for the history of the text”)

Thus, purer does not mean that the text is devoid of problems, far from it. It means that during the copy it has not been altered, or tempered with, by way of the copyist’s interpretation of the text. In this sense, it is more faithful to the document it reproduces, even though the reproduction is imperfect. We will return to the manuscript hosted at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in a moment.

From the manuscripts, the text evolved into printed editions. The first complete printed edition of all of the ten books of Lives appeared in Latin, in Rome, in 1472. It was made from a translation by Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439) and is known as the Versio Ambrosiana. Traversari based his translation mostly on a continuous Greek manuscript produced for him by Demetrio Scarano around 1419-1420. It is known as MS H or Laurentianus 69.35. This manuscript currently belongs to the collection of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, in Florence. It can be examined online in two different places. First at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana website, provided the browser is equipped with a properly configured version of Java (at the time of writing, the system used to visualize manuscript online was not working). Second, it can be accessed via Internet Culturale, the Cataloghi E Collezioni Digitali Delle Biblioteche Italiane: see item IT:FI0100_Plutei_65.23.

Internet Culturale hosts digital copies of at least three other manuscripts of the Lives: see items Plut.89inf.48 (Latin; with the inscription Ambrossi Camaldulensis version Diogenis Laertii De Vitis Philosoph.), Plut.65.21 (Latin; official exemplar of Ambrogio Traversari’s autograph copied by Michele di Giovanni and signed on February 8, 1433; see especially page 170), and Plut.65.23 (Latin).

In the document he prepared, Pierre Wechter observes that the problem with the quote attributed to Aristotle is already present in this first printed edition, where it reads o amici amicus nemo (O friends, there are no friends). A further verification shows that this form –with the vocative interjection– is already present in the Greek manuscript H that was used to produced the Latin translation. We will examine the relevant page of the manuscript in a moment.

Pierre Wechter refers to Jean Céard, who has it that Montaigne used this first Latin edition when he made the handwritten note in the margin of his Essays (see Essais, Paris: Livre de Poche, 2001, p. 294, note 1). Ullrich Langer refers to Pierre Villey’s edition of the Essais (Paris: Nizet, 1992) who lists a Latin edition published in Lyon in 1556 as the one Montaigne used (see Langer, 1994: 18, note 9). This later edition is also available online at Hathi Trust Digital Library (see page 303 for the quote o amici amicus nemo). It is very likely that the 1556 edition is a reprint (apud Antonium Vincentium) of the translation by Traversari. In any case, Langer reminds his reader that Montaigne also owned a Greek edition of the Lives (Ibid.).

From the Latin translation in 1472, it will still take more than sixty years before the first complete edition in Greek is produced. It was edited by Jérôme Froben (Hieronymus Frobenius) and published in Basel, in 1533. This edition, known as the Frobeniana, is based on a single manuscript known as MS Z, currently at the National Library of the Czech Republic. Here is how Tiziano Dorandi describes this manuscript:

The editio princeps (Frobeniana) took as a model a single manuscript, still preserved, of dire quality and extremely contaminated (Z). It therefore disseminated a text of the Lives that was entirely unreliable, often corrupted and interpolated (…) (2013: 11)

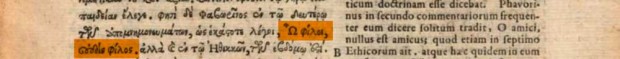

As it turns out, this first Greek printed edition is available online. One can thus see for himself or herself how the problematic quote being discussed here appeared for the first time in printed Greek characters. In Google Books, the pages of the digitized copy appear in reverse order: the frontispiece is at the very end, and one has to scroll up to progress from the first page to the last. The life of Aristotle is to be found, as expected, in the fifth book (ΒΙΒΛΙΟΝ Ε). The quote –which is highlighted below– appears at the bottom of page 223 (full page):

In this first complete Greek edition of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives from 1533, the quote thus reads: “ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος” which indeed translates as “O friends, there are no friends”.

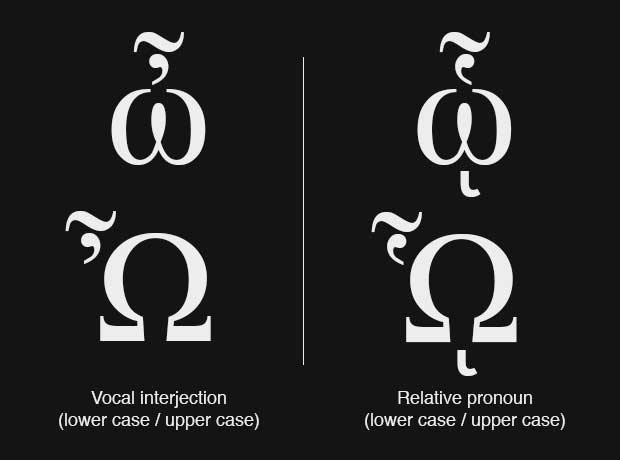

Now it is possible to assess precisely the difference between this version, which was considered canonical during the Renaissance, and the modern one, quoted earlier. It holds strictly to the diacritic marks associated with the first letter: ω (omega).

In the version from 1533, based on a “entirely unreliable, often corrupted and interpolated” manuscript, the ὦ indicates a vocative interjection (see Perseus). In the modern version, the ᾧ is formed with a different diacritic (see below), and with the addition of a iota subscript, mentioned by Agamben: it is a relative pronoun in masculine singular dative form (again at Perseus).

As I suggested earlier, the same vocative interjection (ὦ) is also found in MS H, which dates from 1419/20, and which served as reference for the production of the first printed edition of the Lives in Latin. In the detail below, which appears on page 94 verso (JPG), I have emphasized both the quote and the lower case ὦ.

In the older manuscript P (eleventh or twelfth century) hosted at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the quote can be found on page 200 (or f200; JPG). Below, I have emphasized both the quote, and the lower case ὦ. As it is the case in MS H, the absence of an iota subscript, as well as the diacritic curved to the left, both indicates that this manuscript also conveys the quote in the vocative interjection form: “O friends, there are no friends”.

As it was pointed out earlier MS P is one of the three oldest continuous manuscripts of the Lives. Tiziano Dorandi’s stemma, shown below, allows to better appreciate where it stands in regard to other manuscripts:

Was the vocative interjection already used in the interpolated parent Ω? Was it present in the purer B? I asked Tiziano Dorandi for his informed opinion on the matter and he generously shared the following remarks.

The oldest (interpolated) manuscript Χ, from which all others derived, was written in uncial: upper case letters only, without accents. Therefore, the quote most likely started with “Ω”, in upper case, without any accents, diacritics, nor iota subscript (or adscript). When the next generation of manuscripts were transliterated to lower case, around the ninth century, it was chosen to interpret the “Ω” as a vocative interjection. This form –“O friends, there are no friends”– was carried in the most ancients manuscripts still in existence: B (before it was corrected in B2), P (as we have seen), F and Φ.

The form using the relative pronoun in dative form “ᾧ” came into existence as a conjecture or a correction made by the anonymous scribe who revised B into B2 during the twelfth century.

• • •

At this point, we have located with some precision the origin of the apocryphal quote in the first printed copies of both Latin and Greek editions. We have traced its presence back to older manuscripts as well, all the way to the oldest continuous manuscripts still in existence. We have collected visual examples of the quote as it appears in MS P (11/12th) and MS H (15th). We also know the nature of the difference between the two versions of the quote, which boils down to some diacritic marks on the first letter.

It is now time to turn our attention to the modern version. Why is the quote “O friends, there are no friends” now considered apocryphal? On what ground is it possible to choose between the vocative interjection and the relative pronoun in dative form? To answer this question, Agamben turns his attention to a copy of the Lives printed in the early seventeenth century and, more precisely, to the work of a man who was regarded as one of the most erudite philologist of his time: Isaac Casaubon.

• Isaac Casaubon

Agamben answers the “mystery” of how the quote attributed to Aristotle in the Lives came to change by way of an observation made by the Renaissance scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614):

In 1616, a new edition of the Lives appeared, edited by the great Genevan philologist Isaac Casaubon. Reaching the passage in question -which still read o philoi (O friends) in the edition established by his father-in-law Henry Estienne- Casaubon without hesitation corrected the enigmatic lesson of the manuscripts, which then became so perfectly intelligible that it was taken up by modern editors. (“The Friend” in What Is an Apparatus?, [2004]2009. p. 27)

Casaubon was a significant figure in classical philology. His life is well documented in various biographies produced during the nineteenth century. We have a fairly good idea why his first philological observations were published anonymously (see below), and just how tormented was his relation with his father-in-law, the renowned printer Henri Estienne. The following excerpt from a bibliography published in 1813 provides a good description of the formative years of the master philologist. Additional documents are provided at the end of this post.

He was educated at first by his father, and made so quick a progress in his studies, that at the age of nine he could speak and write Latin with great ease and correctness. But his father being obliged, for three years together, to be absent from home, on account of business, his education was neglected, and at twelve years of age he was forced to begin his studies again by himself but as he could not by this method make any considerable progress, he was sent in 1578 to Geneva, to complete his studies under the professors there, and by indefatigable application, quickly recovered the time he had lost. He learned the Greek tongue of Francis Portus, the Cretan, and soon became so great a master of that language, that this famous man thought him worthy to be his successor in the professor’s chair in 1582, when he was but three and twenty years of age. (The General Biographical Dictionary, Volume 8, by Alexander Chalmers, 1813, p. 353-354)

We will examine Casaubon’s observation in a moment, but first a few words about Agamben’s explanation.

Agamben locates Casaubon’s observation in a new bilingual, Greek and Latin edition of the work of Diogenes Laertius published in 1616 by Casaubon’s father-in-law Henri Estienne, also known as Henricus Stephanus (1528 or 1531–1598, himself a renowned classical scholar and printer; Casaubon was married to his daughter Florence Estienne). This is not inexact, but it is slightly misleading for a couple of reasons.

Henri Estienne died in 1598. The edition Agamben is talking about –which includes Casaubon’s observations– is actually the third edition of a book that was produced by Henri Estienne nearly half a century earlier, in 1570: Diogenis Laertii De Vitis, Dogmatis & Apophthegmatis Clarorum Philosophorum Libri X.

Henri Estienne established the Greek text of his edition with the use of various Italian manuscripts he possessed (I take that, again, from Tiziano Dorandi’s 2013 critical edition of the Lives). It was accompanied by the Latin translation of Ambrogio Traversari. This edition is known as the Stephanianae. The very first time it was published, in 1570, it contains only the notes of Henri Estienne, but starting with the second edition in 1593, they all included Casaubon’s annotations. The editions produced by Henri Estienne’s are often identified by the words “EXCVD HENR. STEPH.” or “EXCVD H. STEPH.” or “EXCVD. STEPH.”, which stands for Excudebat Henricus Stephanus: “made” or “printed” by Henri Estienne.

Agamben must be referring to the third edition, produced after Henri Estienne’s death by his son Paul Estienne. Various copies of this third edition seem to exist, and they all include Casaubon’s comment about Aristotle’s apocryphal quote.

One was produced in Geneva by Iacobum Stoer (or Jacobum Stoer) and is dated from 1615, although some copies show the date 1616. Another one was produced by Joannes Vignon in 1616, in Cologny (Geneva). This edition is available online: the relevant comment by Casaubon regarding Aristotle’s apocryphal quote appears on page p. 75.

About the discrepancy between the date 1615 and 1616, one can see Laertiana: Capitoli sulla tradizione manoscritta e sulla storia del testo delle “Vite dei filosofi” di Diogene Laerzio by Tiziano Dorandi, 2009, p. 40; Bibliotheca Sunderlandiana by Charles Spencer Earl, 1881, p. 307; Bibliotheca Britannica, or a general index to British and foreign literature, Volume 1, by Robert Watt, 1824, p. 306. In the latest critical edition The Lives of Eminent Philosophers published in 2013, Tiziano Dorandi also discuses this problem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 876-78).

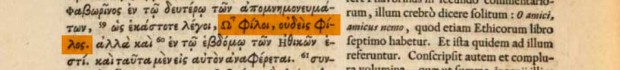

But the story doesn’t end there. Casaubon had in fact already published his observations independently by 1583, ten years before his father-in-law, Henri Estienne, decided to include them in the second edition of his De Vitis, and 33 years before the copy examined by Agamben was produced. The observations were published as a standalone text (without an accompanying reproduction of De Vitis), under the pseudonym Isaaci Hortiboni, and with the title In Diogenem Laertium Notae Isaaci Hortiboni.

This book from 1583 contains the exact same comment as the one printed in the edition produced by Joannem Vignon in 1616: the same one Agamben must have stumbled upon during his visit at the library. In fact, a verification shows that Casaubon’s comment regarding the apocryphal quote will be repeated without modification in many different editions produced during the 17th century, all the way to the 19th century as well (see below).

Now that the origin of the clarification by Causaubon is well established, the comment itself can be examined. In this first edition of Casaubon’s Notae regarding Diogenes Laertius’s text, the relevant comment regarding the quote attributed to Aristotle appears on page 162 (JPG), as follows:

Below is the French translation of Casaubon’s observation offered by Pierre Wechter in his document, followed by an English translation I produced from it. I use H. Rackham’s 1934 translation for the excerpt from the Nicomachean Ethics (at Perseus).

Je lis ᾧ φίλοι. Car que certains lisent ᾧ πολλοὶ φίλοι, comme on le trouve dans le 7e livre de l’Éthique à Eudème, ne me convainc pas. Il est en effet possible qu’Aristote se soit servi par écrit d’une expression différente de celle qu’il employait dans son parler quotidien, sans compter que cette façon de dire semble bien plus belle et mieux tournée en omettant πολλοὶ, déjà implicite dans φίλοι. La même opinion est d’ailleurs répétée dans l’Éthique à Nicomaque en Θʹ [au livre 9]. Oἱ δὲ πολύφιλοι (dit le philosophe) καὶ πᾶσιν οἰκείως ἐντυγχάνοντες οὐδενὶ δοκοῦσιν εἶναι φίλοι, πλὴν πολιτικῶς [ceux qui ont de nombreux amis, et qui font à tout le monde un accueil amical et familier, passent pour n’être amis de personne si ce n’est qu’ils sont sociables]

I read ᾧ φίλοι. For the fact others read ᾧ πολλοὶ φίλοι, as we find it in the 7th book of the Eudemian Ethics, does not convince me. It is indeed possible for Aristotle to have used in writing a different expression than the one he used in his daily speech, notwithstanding the fact that this way of saying sounds nicer and is better formed when πολλοὶ –already implicit in φίλοι– is omitted. Moreover, the same opinion is repeated in the Nicomachean Ethics in Θʹ [in Book 9, 1171a15]. Oἱ δὲ πολύφιλοι (says the philosopher) καὶ πᾶσιν οἰκείως ἐντυγχάνοντες οὐδενὶ δοκοῦσιν εἶναι φίλοι, πλὴν πολιτικῶς [Persons of many friendships, who are hail-fellow-well-met with everybody, are thought to be real friends of nobody (otherwise than as fellow-citizens are friends)]

There are two interesting things to consider. First, Casaubon doesn’t even comment on the modification of ὦ φίλοι into ᾧ φίλοι. For him, it seems to go without saying: the subject here has nothing to do with an alleged interjection to some friends about the paradoxical absence, or non-existence of friends: “O friends, there are no friends”. Instead, for the Renaissance philologist, the subject is about the plurality of friends, the quantitative problem of friendship. Casaubon’s only discussion is whether or not to add πολλοὶ (“of number, many”) in front of φίλοι. He is against it, but this form will nonetheless sometimes be used in modern editions (“He who has many friends…”).

Why is it so obvious that Aristotle’s saying concerns a quantitative consideration about the number of friends one has, or should have? The second thing to consider, then, is how Casaubon informed his judgment. The crucial piece of information is already in the text of the Lives. Indeed, as we have seen earlier, Diogenes Laertius actually documented his claim about Aristotle’s famous saying: “Further, this is found in the seventh book of the Ethics” (“ἐν τῷ ἑβδόμῳ τῶν Ἠθικῶν ἐστι”).

The reference is to the seventh book of the Eudemian Ethics. In 1245b20, Aristotle specifically discusses the quantitative problem of friendship: just how many friends shall one have? I take the English translation from H. Rackham (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), and I have emphasized the part that is of special interest here. The Greek text follows with the same part being emphasized as well.

As to seeking for ourselves and praying for many friends, and at the same time saying that one who has many friends has no friend, both statements are correct. For if it is possible to live with and share the perceptions of many at once, it is most desirable for them to be the largest possible number; but as that is very difficult, active community of perception must of necessity be in a smaller circle, so that it is not only difficult to acquire many friends (for probation is needed), but also to use them when one has got them. (Eudemian Ethics, 1245b20-26)

καὶ τὸ ζητεῖν ἡμῖν καὶ εὔχεσθαι πολλοὺς φίλους, ἅμα δὲ λέγειν ὡς οὐθεὶς φίλος ᾧ πολλοὶ φίλοι, ἄμφω λέγεται ὀρθῶς. ἐνδεχομένου γὰρ πολλοῖς συζῆν ἅμα καὶ συναισθάνεσθαι ὡς πλείστοις αἱρετώτατον: ἐπεὶ δὲ χαλεπώτατον, ἐν ἐλάττοσιν ἀνάγκη τὴν ἐνέργειαν τῆς συναισθήσεως εἶναι, ὥστ᾽ οὐ μόνον χαλεπὸν τὸ [25] πολλοὺς κτήσασθαι (πείρας γὰρ δεῖ), ἀλλὰ καὶ οὖσι χρήσασθαι. (Eudemian Ethics, 1245b20-26).

Nowhere in the Eudemian Ethics –nor in the Nicomachean Ethics for that matter– is there an excerpt remotely similar to the apocryphal interjection “O friends, there are no friends”. However, once the proper correction has been made to the diacritics associated with the opening omega, the excerpt emphasized above is strikingly similar to the quote shared by Diogenes Laertius.

As we have seen, Casaubon also points in his comment to an excerpt in Book 9 of the Nicomachean Ethics, where Aristotle expresses a very similar view: those who want to be friends to everyone “are thought to be real friends of nobody”. This point is repeated again earlier, in 1170b20, at the very beginning of Book 9, Chap. 10:

Ought we then to make as many friends as possible? or, just as it seems a wise saying about hospitality— “Neither with troops of guests nor yet with none”— so also with friendship perhaps it will be fitting neither to be without friends nor yet to make friends in excessive numbers. (1170b20; the quote used by Aristotle is actually from Hesiod’s Works and Day, 715)

The point is repeated in a number of occasions, in various forms. Therefore, there is some ground to the claim the saying was an “habitual saying” for Aristotle.

Besides, Casaubon is not the only philologist of his time to have come to this conclusion. Although Agamben does not mention him, Italian philologist Piero Vettori (1499-1585) also identified the apocryphal quote as being problematic, and made a similar observation about it.

In his commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics published in 1584 –one year after Casaubon’s own Notae– Vettori remarks that Aristotle is unlikely to have said “O friends, there are no friends”. Instead, Vettori follows Dioeges Laertius’s reference and invokes the Eudemian Ethics to correct the quote (the same segment I have already quoted above): it is, in reality, a quantitative critique of friendship.

Vettori’s explanation appears on page 545 of his Commentarii in X libros Aristotelis de moribus ad Nicomachum published in 1584. In the index of the same volume, the comment is mentioned in the following way: Diogenis Laertii locus emendatus (“passage corrected”; p. 629). It remains to be determined if the comment was published elsewhere, in some earlier editions. For example, Vettori published a bilingual Greek/Latin edition of the Nicomachean Ethics in 1560.

Vettori’s explanation was written in Latin. Once again, Pierre Wechter generously offered his help and produced both a transcription from the image of the text, and a French translation as well. I did my best to produce a faithful English translation from the French.

Dans le 7e livre de l’Éthique à Eudème, où Aristote expose avec soin et en détail sa conception de l’amitié, il pose la question en y distinguant deux aspects : il enseigne en effet qu’il y a deux opinions qui, tout en étant contradictoires, sont vraies, à les considérer en elles-mêmes, comme on le doit, et non pas en les prenant à la lettre ; car on a raison de dire qu’il faut que les hommes cherchent à avoir de nombreux amis et même qu’ils doivent en faire la prière aux Dieux. Mais, en même temps, on a raison de dire que n’a aucun ami celui qui en a une foule. Comment se défendent les deux points de vue sans erreur, il le montre clairement comme aussi dans le 9e livre de l’Éthique à Nicomaque. Saisissant donc l’occasion, je veux rétablir un passage dans le chapitre de Diogène Laërce qui traite de la vie d’Aristote ; en effet, vers la fin, quand il rappelle les paroles sages et pénétrantes d’Aristote, il rapporte que selon le philosophe Favorinus, dans ses Mémorables, Aristote avait souvent à la bouche la première citée des deux opinions, «ô mes amis, point d’amis». Or le passage est défectueux et il faut vraiment lire «pour qui a des amis nombreux, il n’y a pas d’amis», car partout, dans l’œuvre d’Aristote, on peut trouver l’ensemble du passage en question: «D’autre part, dire que nous devons chercher à nous faire de nombreux amis et les désirer, et dire en même temps qu’avoir beaucoup d’amis, c’est n’avoir point d’ami, ce sont deux choses où il n’y a rien de contradictoire ; et, des deux côtés, on a raison» et la suite. (Pierre Wechter borrows the French translation of the Greek sentence to J. Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire, 1856).

In the 7th Book of the Eudemian Ethics, where Aristotle exposes with great care and in detail his conception of friendship, he asks the question by distinguishing between two aspects: indeed, he teaches there are two opinions which, while being contradictory, are true, when considered together, as one should, and not by taking them to the letter; for one is right in saying that men seek to have many friends and even that they should pray for it to the Gods. But at the same time, one is right in saying that he has no friend, he who has too many. How those two points of view can be adequately defended, he goes on to show it also clearly in the 9th Book of the Nicomachean Ethics. I would like to take the opportunity to correct a segment in the chapter where Diogenes Laërtius wrote about the life of Aristotle; indeed, towards the end, when he recalls the wise and penetrating sayings by Aristotle, he reports that according to the philosopher Favorinus, in his Memorabilia, Aristotle was in the habit of often repeating the first of the two opinions quoted, “o my friends, there are no friends”. Yet this segment is defective and one must really read “for he who has many friends, there are no friends”, since everywhere, in the work of Aristotle, one can find the context in which this segment appeared: “As to seeking for ourselves and praying for many friends, and at the same time saying that one who has many friends has no friend, both statements are correct. (I borrow the translation for the Greek sentence from H. Rackham, 1981: see Eudemian Ethics, 1245b20-26)

That is why, in light of all those observations, the quote “O friends, there are no friends” is now considered to be apocryphal, from a philological perspective. It is also the reason why it has disappeared from the modern editions of the Lives.

• • •

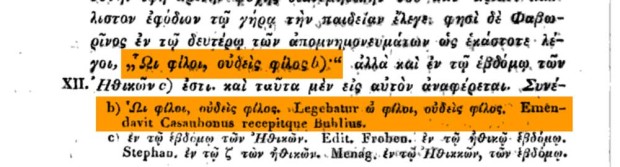

Before we conclude, it is important to stress out one last point. As Tiziano Dorandi kindly explained, the quote was corrected in MS B2. But this correction was not carried in the printed editions –Latin or Greek– published later, which were based on more contaminated manuscripts.

Agamben wrote hastily that “Casaubon without hesitation corrected the enigmatic lesson of the manuscripts”. However, in the edition of the Lives examined by Agamben, the quote still reads ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος, “O friends, there are no friends” (on page 314: JPG):

(The reader will notice that the diacritic follows the upper case omega. This is not a variation in meaning, but a variation in typographic conventions that occur during the Renaissance. Those conventions would eventually settle at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Today, diacritics always precede the upper-case letter.)

Casaubon’s observation is included in this edition, but the text itself isn’t altered. In fact, despite Casaubon’s observations –first published in 1583– the apocryphal quote will remain in place, as is, for yet another two centuries and a half. It will be repeated again and again in various editions of the Lives published between the fifteenth and the nineteenth centuries, as shown below. This, in turn, explains why the quote “O friends, there are no friends”, despite being apocryphal, has nonetheless acquired a certain degree of canonical authority over time.

Below, I show how the quote appears in each of the editions of Diogenes Laertius’s Lives I was able to found online (which is most of them).

The second edition of Henri Estienne’s Greek/Latin text of the Lives published in 1593. The quote ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος appears on page 314. For the first time, it includes Isaac Casaubon’s observations. Although Casaubon had published his notes anonymously ten years earlier, it’s the first time they appear in the same volume as the text of the Lives. His remark on the quote attributed to Aristotle appears on page 75 of the section titled “Isaaci Casauboni Notæ Ad Dionegis Laertii libros de vitis, dictis & decretis principum philofophorum. Edito altera, auctior & emendatior.”

Another edition by Henri Estienne dated from 1594. The quote ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος also appears on page 314. Casaubon’s remark on the quote attributed to Aristotle appears on p. 134 of the digital document hosted at the Hathi Trust Digital Library. This is considered to be the same edition as the one from 1593, only bearing a different date. The original is conserved at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

A 1664 reprint by John Pearson of a different edition from 1594, which was edited this time by Tommaso Aldobrandini. I couldn’t find a digital copy of this 1594 edition, which is known as the Aldobrandina. The reprint from 1664 is known as the Pearsoniana, and it was published in London. It includes commentaries by Gilles Ménage and notes by Henri Estienne, Isaac Casaubon and Méric Casaubon. Within this edition, the quote ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος is on page 119, while Casaubon’s comment appears on page 43 of the section “Isaaci Casauboni Notæ ad Dionegis Laertii”.

In a 1692 edition with Greek and Latin text by Marcus Meibom, published in Amsterdam, with notes by Henri Estienne, Gilles Ménage, Isaac Casaubon, Tommaso Aldobrandini and Joachim Kühn. This edition is known as the Meibomiana. The quote ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος and the relevant observation by Casaubon are both on page 280 (see note 59 for Casaubon).

The following edition, which I believe was the only new one edited in the eighteenth century, was produced by Daniel Longolius (Paullo Danielle Longolio) and published in 1739. We learn from Tiziano Dorandi that although the text is identical to the one edited by Marcus Maibom, this edition provides a new structure for each of the single lives. The quote attributed to Aristotle appears on page 481 of Volume I.

It is only in Volume I of the 1828 edition prepared by Heinrich Gustav Hübner that the text be finally modified to reflect Casaubon’s observation, published 245 years earlier. On page 326, Hübner will add the notice: “Legebatur ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος. Emendavit Casaubonus recepitque Bublius.”. And the quote itself, as shown below, starts with a pronominal dative omega in upper case.

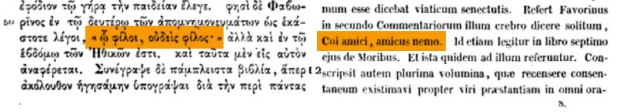

The 1850 edition published in Paris by Carel Gabriel Cobet –which Tiziano Dorandi calls the “first modern ‘critical’ edition”– carries this correction both in Greek and in Latin (which now reads Cui amici, amicus nemo). In this edition, known as the Cobetiana, the quote appears on page 115.

• Conclusion

In 1988 and 1989, Jacques Derrida conducted a seminar with the title “Politics of Friendship” at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes. Each of its sessions opened with the words of Montaigne, reproducing the apocryphal quote attributed to Aristotle. Anyone familiar with the philosophy of Jacques Derrida will have already understood that the philosopher eloquently feasted on the différance between the two versions. Here is how he commented –in the book that came out of those sessions– on the nature of the grammatical problem we have explored above.

It would all come down to a difference in the way of accentuating, chanting, therefore of addressing the other. Would such a history really have depended on a single letter, the ω, the omega opening its mouth and tossing a sentence to the other? Hardly anything at all? Less than a letter?

Yes, it will have been necessary to decide on an aspiration, on the softness or hardness of a ‘spirit’ coming to expire or aspire a capital O, an ω: is it the sign of a vocative interjection, ω, or that of a pronominal dative, ω with a hoi, and hence an attribution – the friend, φίλοι, remain motionless, indifferent to what is happening to them in either case, the vocative or the nominative?

ὦ φίλοι, οὐδεὶς φίλος

What does that change? Everything, perhaps. And perhaps so little. We shall have to approach prudently, in any case, the difference created by this trembling of an accent, this inversion of spirit, the memory or the omission of an iota (the same iota synonymous in our culture for ‘almost nothing’). (The Politics of Friendship, New York: Verso, [1994]2005, pp. 189-190, with corrections)

Incredibly –given what is at stake here– the English edition managed to omit the diacritic on the ω when the entire quote is used (it also uses the wrong sigma in word-final position). The Greek transcription in the above quote is therefore based on the one used in the original French edition from 1994.

![TOP: The Politics of Friendship, New York: Verso, [1994]2005, pp. 189; BOTTOM: Politiques de l'amitié, Paris: Galilée, 1994, p. 217](https://aphelis.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/DERRIDA_1994-2005_Politics_of_Friendship_comparison-620x267.jpg)

From a strict philological perspective, there subsists little doubt nowadays –if any– about which version is most likely to have been written down by Diogenes Laertius. In his book, Derrida finds the apocryphal quote “O friends, there are no friends” to be a “brilliant invention” that “[n]o philological fundamentalism will ever efface” (2005, p. 207). Yet, even though he makes no mention of Casaubon (to the surprise of Agamben who apparently had shared the information with him), nor of Vettori, Derrida is nevertheless compelled to come to the same conclusion:

There is in effect an improbable version, the one we know, the one we have been ceaselessly citing: the odds are less in its favour, as we shall attempt to show, and nothing convincing can come to its defence. (Ibid.)

Unsurprisingly, Derrida sees politics in the various gestures conforming or exploiting the difference between the two forms of the quote (he saw politics in etymological demonstrations as well). Agamben agrees with him, it seems, when he suggests the choice Derrida made not to mention Casaubon’s observation was a strategic choice (2005: 28).

What about Nietzsche? He was not only a very keen philologist himself, he was on top of that a specialist of the work of Diogenes Laertius. Yet, the augmented edition of Human, All Too Human from 1828 where he used the apocryphal quote was published 58 years after it had been corrected by Heinrich Gustav Hübner. Did Nietzsche miss it? Or did he choose to ignore the correction? And if so, why? Nietzsche, like Derrida and Agamben after him, spent time thinking about authorship, authority and authenticity.

For all that, it certainly does not mean the form “O friends, there are no friends” should be abandoned, condemned to oblivion or too hastily labeled as being “wrong” or “incorrect”. It may very well be an apocryphal quote, but it is nonetheless draped in canonical authority provided by ten centuries of repetition and commentaries.

Since the sixth century, this quote has been transliterated from upper case to lower case, opening the door to the introduction of different diacritic marks. It has been translated from Greek to Latin, to German, to French, to Spanish and to English, opening the door to the introduction of more variations. It also has been transliterated from Greek characters to Latin characters (as it is the case in Agamben’s essay), with or without regard to conventions (PDF), opening the door to still more variations. Quite amazingly, despite or maybe because of those issues, Aristotle’s saying about friendship reached us today. Peter Sloterdijk once made a similar observation about philosophy which, I believe, is of particular relevance in the case at hand here:

That written philosophy has managed from its beginning more than 2500 years ago until the present day to remain communicable is a result of its capacity to make friends through its texts. It has been reinscribed like a chain letter through the generations, and despite all the errors of reproduction –indeed, perhaps because of such errors– it has recruited its copyists and interpreters into the ranks of brotherhood. (“Rules for the Human Zoo: a response to the Letter on Humanism”, tr. by Mary Varney Rorty) [1999]2009).

As I suggested in the introduction, this essay is not meant to settle things down once and for all. It is rather an invitation to carry the friendly discussion forward.

• • •

Additional documents pertaining to the life of Isaac Casaubon available online:

- For a biography in Latin established in 1774: Isaaci Casauboni de satyrica Græcorum poesi & Romanorum satira libri duo by Ioannes Iacobus Rambach, p. 401 onward (jump to a bibliography starting on p. 429).

- An excerpt of Chalmers’s biography was reproduced in 1815, in Vol. XII of The Classical Journal (September and December) printed by A.J. Valpy (see page 172 onward).

- The Fruits of Endowments by Frederick Robert Augustus Glove, 1840, p. 58. It quotes the previous biography by Alexander Chalmers (above).

- Isaac Casaubon, 1559-1614, a biography by Mark Pattison published in 1875.

-

Finally, IdRef has an exhaustive bibliography of documents produced by and about Casaubon.

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: Agamben, Aristotle, community, Derrida, Diogenes Laertius, friendship, Montaigne, Nietzsche, philology