An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

Like most homes in this part of Japan, the house consisted of a wooden frame and wooden walls supporting a heavy tile roof. Its front hall, packed with rolls of bedding and clothing, looked like a cool cave full of fat cushions. Opposite the house, to the right of the front door, there was a large, finicky rock garden. There was no sound of planes. The morning was still; the place was cool and pleasant.

Then a tremendous flash of light cut across the Sky. Mr Tanimoto has a distinct recollection that it travelled from east to west, from the city towards the hills. It seemed a sheet of sun. Both he and Mr Matsuo reacted in terror – and both had time to react (for they were 3,500 yards, or two miles, from the centre of the explosion). Mr Mazsuo dashed up the front steps into the house and dived among the bed- rolls and buried himself there. Mr Tanimoto took four or five steps and threw himself between two big rocks in the garden. He bellied up very hard against one of them. As his face was against the stone he did not see what happened. He felt a sudden pressure, and then splinters and pieces of board and fragments of tile fell on him. He heard no roar. (Almost no one in Hiroshima recalls hearing any noise of the bomb. But a fisherman in his sampan on the Inland Sea near Tsuzu, the man with whom Mr Tanimoto’s mother- in-law and sister-in-law were living, saw the flash and heard a tremendous explosion; he was nearly twenty miles from Hiroshima, but the thunder was greater than when the B-29s hit Iwakuni, only five miles away.)

☛ Hiroshima by John Hersey, London: Penguin, 1946, pp. 17-18.

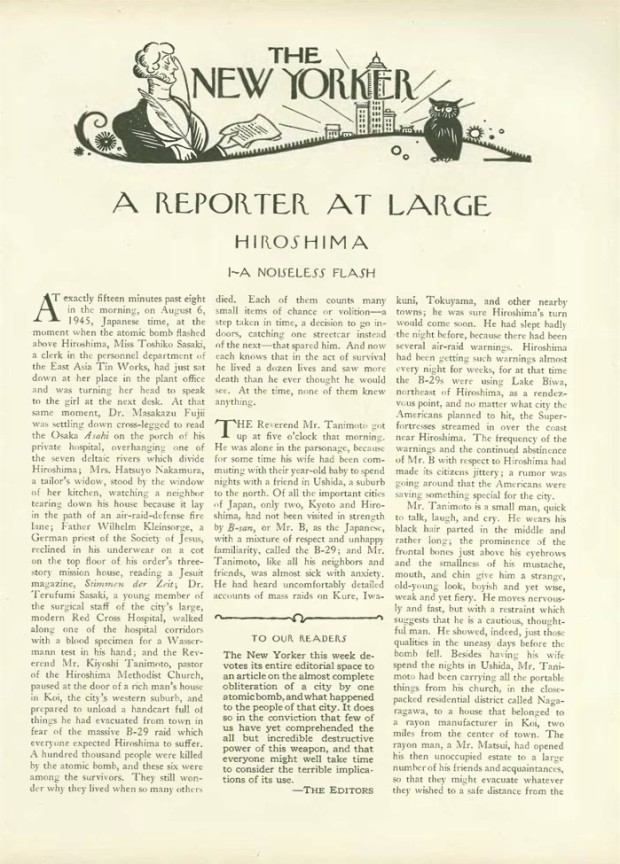

John Hersey’s 31,000 words essay about the life of six Hiroshima survivors first ran in the pages of The New Yorker, in the issue of August 31, 1946 (from page 15 to page 68). Although a subscription is needed to access the full text at The New Yorker, a digital version of the edition later published by Penguin is available online at Archive.org. From the publisher note printed with the first Penguin edition:

ON Monday 6 August 1945 a new era in human history opened. After years of intensive research and experiment, conducted in their later stages mainly in America, by scientists of many nationalities, Japanese among them, the forces which hold together the constituent particles of the atom had at last been harnessed to man’s use: and on that day man used them. By a decision of the American military authorities, made, it is said, in defiance of the pre-tests of many of the scientists who had worked on the project, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. As a direct result, Some 60,000 Japanese men, women, and children were killed, and 100,000 injured; and almost the whole of a great seaport, a city of 250,000 people, was destroyed by blast or by fire. As an indirect result, a few days later, Japan acknowledged defeat, and the Second World War came to an end. […]

Hersey’s vivid yet matter-of-fact story tells what the bomb did to each of these six people, through the hours and the days that followed its impact on their lives. It is written soberly, with no attempt whatever to ’pile on the agony’ – the presentation at times is almost cold in its economy of words. To six ordinary men and women, at the time and afterwards, it seemed – like this.

The New Yorker’s original intention was to make the story a serial. But in an inspired moment the paper’s editors saw that it must be published as a single whole and decided to devote a whole issue to Hersey’s master-piece of reconstruction. For ten days Hersey feverishly rewrote and polished his story, handing it out by instalments to the printers, and no hint of what was in the air escaped from the New Yorker office. On 31 August, in the paper’s usual format, the historic issue appeared. It created a first-order sensation in American journalistic history: a few hours after publication the issue was sold out. Applications poured in for permission to serialize the story in other American journals, among them the New York Herald Tribune, Washington Post, Chicago Sun, and Boston Globe. A condensed version – the cuts personally approved by Hersey – was broadcast in four instalments by the American Broadcasting Company. Some fifty newspapers in the US, eventually obtained permission to use the story in serial form, the copyright fees, after tax deduction, at Hersey’s direction going to the American Red Cross. Albert Einstein ordered a thousand copies of the New Yorker containing the story. (New York: Penguin, 1946, pp. v, vii-viii; this publisher note is not included in the edition published the same year by Random House in the United-States, in its The modern Library collection)

There are a couple of accounts of the production and reception of John Hersey’s essay. Two years after the essay was published, The Journal of Social Psychology published an article titled “Reaction to John Hersey’s “Hiroshima”” (Joseph Lufta & W. M. Wheelera, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1948, pp. 135-140; subscription may be required). Nearly thirty years later, the Pacific Historical Review published “John Hersey and the American Conscience: The Reception of “Hiroshima”” by Michael J. Yavenditti (Vol. 43, No. 1, February 1974; subscription may be required). Here’s how the opening paragraph of this second paper reads:

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and Nagasaki, three days later, has spawned a considerable literature by survivors, journalists, novelists, scholars, and official governement sources. Several films on the development of the atomic bomb (the Manhattan Project), the decision to use it, and the ordeal of its victims have reached limited audience in America and abroad. Yet of all the accounts of the atomic bombings, probably none has been more widely read and appreciated by Americans than John Hersey’s Hiroshima. (p. 24)

In 1997, Steve Rothman wrote a well-documented term paper for a class he was taken at Harvard University, and which he made freely available online: “The Publication of Hersey’s “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker”. His website HerseyHiroshima.com also offers additional material pertaining to Hersey’s essay.

Previously: “Commandments in the Atomic Age” by Günther Anders, 1957

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Technology

- Tagged: atomic, bomb, bombing, Hiroshima, Japan, John Hersey, journalism, nuclear, war, World War