An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

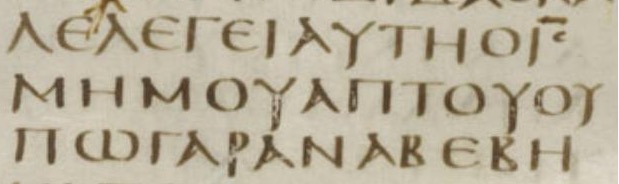

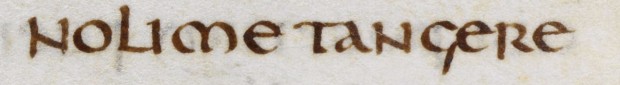

Love and truth touch by pushing away: they force the retreat of those whom they reach, for their very onset reveals, in the touch itself, that they are out of reach. It is in being unattainable that they touch us, even seize us. What they draw near to us is their distance: they make us sense it [sentir], and this sensing [ce sentiment] is their very sense. It is the sense of touch that commands not to touch. It is time, indeed, to specify the following: Noli me tangere does not simply say “Do not touch me”; more literally, it says “Do not wish to touch me.” The verb nolo is the negative of volo: it means “Do not want.” In that, too, the Latin translation displaces the Greek mē mou haptou (the literal transposition of which would be non me tange). Noli: do not wish it; do not even think of it. Not only don’t do it, but even if you do do it (and perhaps Mary Magdalene does do it, perhaps her hand is already placed on the hand of the one she loves, or on his clothing, or on the skin of his nude body), forget it immediately. You hold nothing; you are unable to hold or retain anything, and that is precisely what you must love and know. That is what there is of a knowledge and a love. Love what escapes you. Love the one who goes. Love that he goes.

☛ Noli me tangere. On the Raising of the Body by Jean-Luc Nancy, tr. by Sarah Clift, Pascale-Anne Brault, and Michael Naas, New York: Fordham University Press, [2003] 2008, p. 37.

Here’s the original French version:

L’amour et la vérité touchent en repoussant: ils font reculer celle ou celui qu’ils atteignent, car leur atteinte révèle, dans la touche même, qu’ils sont hors de portée. C’est d’être inateignable qu’ils nous touchent et qu’ils nous poignent. Ce qu’ils approchent de nous, c’est leur éloignement: ils nous le font sentir, et ce sentiment est leur sens même. C’est le sens de la touche qui commande de ne pas toucher. Il est temps, en effet, de le préciser: Noli me tangere ne dit pas simplement «ne me touche pas», mais plus littéralement «ne veuille pas me toucher». Le verbe nolo est le négatif de volo: il signifie «ne pas vouloir». En cela aussi la traduction latine déplace le grec mè mou haptou (dont la transposition littérale eût été non me tange). Noli: ne le veuille pas, n’y pense pas. Non seulement ne le fais pas, mais même si tu le fais (et peut-être Marie-Madeleine le fait-elle, peut-être sa main s’est-elle déjà posée sur la main de celui qu’elle aime, ou sur son vêtement, ou sur la peau de son corps nu), oublie-le aussitôt. Tu ne tiens rien, tu ne peux rien tenir, et voilà ce qu’il te faut aimer et savoir. Voilà ce qu’il en est d’un savoir d’amour. Aime ce qui t’échappe, aime celui qui s’en va. Aime qu’il s’en aille. (Noli me tangere, Paris: Bayard Éditions, [2003] 2013, pp. 60-61)

• • •

Noli me tangere is part of Jean-Luc Nancy ongoing deconstruction of Christianity (or his effort to expose the auto-deconstructing mode of Christianity: see “The Self-Deconstruction of Christianity”, Aug. 2000). It aims specifically at a non-eschatological interpretation of the doctrine of resurrection. In Nancy’s views, the conditions of life we share in Occident are marked by the opening of an infinite inappropriability. Those conditions, he argues in substance, are already exposed in the Christian representation of resurrection. Therefor, in his views, there cannot be such things as the renovation of a lost essence, a return of, or to proper life, or the raising of an original body/self. On the contrary, when Jesus says to Marie Magdalene “Touch me not”, in John 20:17, he is exposing both the truth of Christianity and of our current coexistential predicament: there is no body to touch, no given meaning to grasp, except the fleeting of all meanings. Everybody’s life is continually passing, transient, and we have nothing to hold except the recognition of our shared finitude. As we are thrown together in the opening of this endless transitivity –Pascal’s “l’homme passe infiniment l’homme” (Br. 434/Laf. 131)–, we must risk ourselves to love without the illusion of possessing anything, or anyone. Thus Nancy observes: “Love what escapes you. Love the one who goes. Love that he goes.” At one point in his analysis, he further unfolds the doctrine of resurrection as a kenosis (κένωσις), that is an event of emptying. His deconstruction of the metaphysic of presence exposes the gap upon which our being-in-common is grounded (the emptiness attached to kenosis is not an absence that would come second to an originary presence: on this topic, see “A Faith That Is Nothing At All” in Dis-Enclosure: The Deconstruction of Christianity, [2005] 2008).

This exercise in deconstruction is clearly related to Heidegger’s Destruktion of the metaphysical and theological understanding of Being, often regarded as an attempt at overcoming “ontotheology”1. In his essay “The Passion of Facticity”, Giorgio Agamben argues that love plays a central role in Heidegger’s Being and Time (Potentialities, 1999). He suggests how, inspired by Augustine’s “Non intratur in veritatem nisi per caritatem”2 (Contra Faustum, 32.18), Heidegger conceived of a kind of “ontological primacy of love as access to truth” (1999: 186). As a path however, love does not lead the Dasein to a determinate truth, nor to a proper meaning. On the contrary, love is the passion of the Dasein’s “facticity”, that is the passion as the mode of being through which the Dasein knows not an essential fact, but the enigma of this very facticity. “Facticity,” writes Agamben, “is the condition of what remains concealed in its opening, of what is exposed by its very retreat. (Agamben, 1999: 190).

What is worth for Mary Magdalene is also telling of the most banal experience of love: the difficult realization that the miraculous presence of the loved one is always attached to the possibility of its eventual retreat, or disappearance (I have suggested elsewhere just how challenging such an experience can be: see Michael Haneke, love and finitude). At the same time, it also illustrates the most widely shared condition among us all. Since the early 80s, Jean-Luc Nancy has been studying this coexistential condition through his relentless unworking of the concept of “community”. For what is at hand here, it will suffice to suggest how, from this standpoint, love reveals that the most intimate is actually the most common, and how onto(theo)logy (or epistemology for that matter: the problem of truth) is a highly political affair.

• • •

1. See Iain Thomson’s “Ontotheology? Understanding Heidegger’s Destruktion of Metaphysics” (International Journal of Philosophical Studies, Vol.8(3), 297–327; PDF).↩︎︎

2. In the English translation of Agamben’s essay, the quote from Augustine contains a typographical error which has been corrected here. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication

- Tagged: aporia, body, Christianism, deconstruction, dialectic, Jean-Luc Nancy, love, teleology, touch, truth