An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

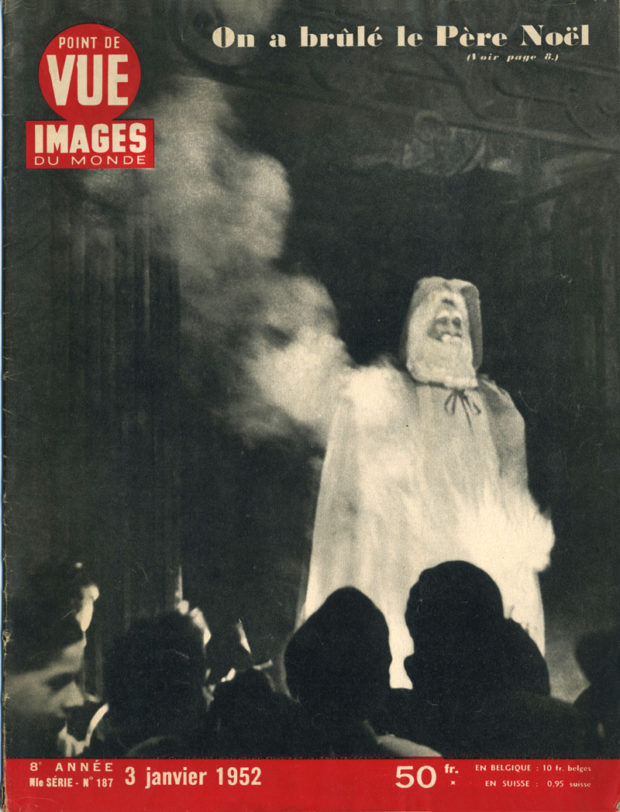

Father Christmas was hanged yesterday afternoon from the railings of Dijon Cathedral and burnt publicly in the precinct. This spectacular execution took place in the presence of several hundred Sunday school children. It was a decision made with the agreement of the clergy who had condemned Father Christmas as a usurper and heretic. He was accused of ‘paganizing’ the Christmas festival and installing himself like a cuckoo in the nest, claiming more and more space for himself. Above all he was blamed for infiltrating all the state schools from which the crib has been scrupulously banished.

On Sunday, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the unfortunate fellow with the white beard, scapegoated like so many innocents before him, was executed by his accusers. They set fire to his beard and he vanished into smoke.

☛ France-Soir, “Sunday School Children Witness Father Christmas Burnt in Dijon Cathedral Precinct,” December 24, 1951. Version française.

The events described above1 are mentioned in an essay published by French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss titled “Le Père Noël Supplicié”. This essay was first published in 1952, in the monthly journal Les Temps Modernes. It was later republished in Nous sommes tous des cannibales (2013). In 2016, it was published as a standalone book with the same title Le Père Noël supplicié. It was first translated into English by Diana Gittins in 1995 under the title “Father Christmas Executed” and was included in the collection Unwrapping Christmas, edited by Daniel Miller.

To put things in perspective, The Elementary Structures of Kinship, one of Lévi-Strauss two doctoral thesis, was defended in 1948 and published the following year, in 1949. Tristes Tropiques –with its famous opening line: “I hate travelling and explorers”– was published in 1955, and the Structural Anthropology in 1958.

In the opening of his 1952 essay on the public burning of an effigy of Father Christmas, Lévi-Strauss succinctly explains the context in which the so-called execution took place:

A number of the clergy had for several months expressed disapproval of the increasing importance given by both families and the business sector to the figure of Father Christmas. They denounced a disturbing ‘paganization’ of the Nativity that was diverting public spirit from the true Christian meaning of Christmas to the profit of a myth devoid of religious value. (1995: 38)

While the whole essay remains relevant –even or especially in a neo-liberal context–, Lévi-Strauss’s “final remark” is worth revisiting. It is exemplary of the all-encompassing and irresistible power of the structural analysis that was about to swept through France intellectual landscape. Indeed, under Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist examination, it becomes clear that it is much easier to burn an effigy in public than is it to actually escape the symbolic function of a ritual structure:

[…] it is a long way from the King of the Saturnalia to Father Christmas. Along the way an essential trait–maybe the most ancient–of the first seems to have been definitely lost. For, as Frazer showed, the King of the Saturnalia was himself the heir of an ancient prototype who, having enjoyed a month of unbridled excess, was solemnly sacrificed on the altar of God. Thanks to the auto-da-fé of Dijon we have the reconstructed [reconstitué] hero in full. The paradox of this unusual episode is that in wanting to put an end to Father Christmas, the clergymen of Dijon have only restored in all his glory, after an eclipse of several thousand years, a ritual figure they had intended to destroy.

Before it signifies the act of putting to death, “execution” means the act of accomplishing something. Through the public burning of an effigy of Father Christmas, Lévi-Strauss exposes the accomplishment of its structural function.

• • •

References

-

France Culture (2006). “Histoire des saints 2/4”, with audio testimonies of participants to the events of 1951, Dec. 19.

-

Berrod, Nicolas (2018). “23 décembre 1951, le jour où le Père Noël a été envoyé au bûcher”, Le Parisien, Dec. 23.

-

Gunthert, André (2012). «Croire au Père Noël», L’atelier des icônes. Carnet de recherches d’André Gunthert (archive), Dec. 24.

-

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1952). «Le Père Noël Supplicié», Les temps modernes, no. 77, pp. 1572-1590, Paris: Gallimard.

-

Lévi-Strauss (1953). «Les avatars du Père Noël ou la psychologie des mythes», Revue des Arts et traditions populaires, avril-juin, pp. 161-163. PDF.

-

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (2013). Nous sommes tous des cannibales, Paris: Seuil, pp. 13-47.

-

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (2016). Le Père Noël Supplicié, with a forward by Maurice Olender, Paris: Seuil.

-

Miller, Daniel (ed.) (1995). Unwrapping Christmas, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 38-51. PDF.

• • •

1. There are some discrepancies online about the date of the alleged “execution” of Father Christmas. This is most likely having to do with a confusion between the date when the events took place (Sunday Dec. 23, 1951, 3PM) and the date –the following day– when they were reported in France-Soir, one of the mostly read French newspaper at the time (Monday Dec. 24, 1951). ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: anthropology, Christmas, Lévi-Strauss, structuralism