An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

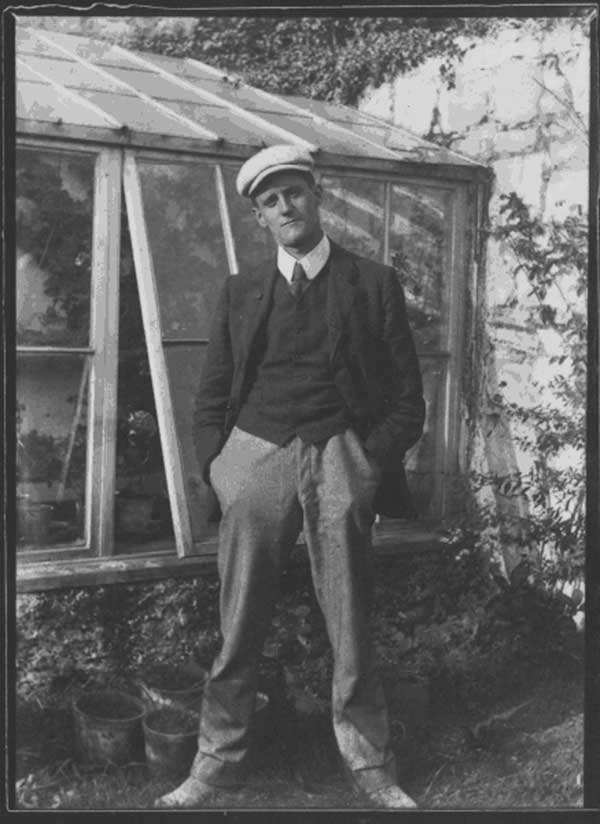

☛ Getty Images: Portrait of Irish writer James Joyce, (1882 – 1941) aged 22, standing outdoors. Photo by C. P. Curran/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Since 1954, June 16 is known worldwide as “Bloomsday”, a celebration of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses. The entire novel is set on June 16, 1904. 1954 marked the fiftieth anniversary of that fictional day. The James Joyce Center in Dublin provides the following explanation for the significance of the date:

We believe that on that day Joyce went out with Nora Barnacle, his future wife, for the first time. Joyce and Nora met for the first time on Friday 10 June 1904 on Nassau Street, near Finn’s Hotel where Nora worked. They arranged to meet again on Tuesday 14 June, outside Sir William Wilde’s house on Merrion Square. Joyce turned up for the meeting but Nora didn’t. Joyce wrote to her at the hotel on 15 June asking if she would like to make another arrangement. According to Joyce’s biographer, they went walking together in Ringsend on 16 June and Joyce later told Nora ‘You made me a man.’ (“What Is Bloomsday”)

French writer Philippe Sollers commented the story when he reviewed the publication of the French translation of James Joyce’s letters to Nora (Lettres à Nora, 2012):

Nous sommes en juin 1904 à Dublin, et deux jeunes Irlandais se rencontrent dans la rue. Elle, Nora, 20 ans, est femme de chambre dans un hôtel de la ville (le «Finn’s», retenez ce nom). Lui, 22 ans, va bientôt signer ses lettres du diminutif de son prénom, Jim, et est déjà sûr d’obtenir un jour une grande gloire littéraire. Son nom ? James Joyce. […]

Elle a fait découvrir le plaisir physique partagé à son compagnon, mais elle produit aussi deux enfants dans la foulée, dont la destinée sera plus ou moins tragique. Jim et Nora ne se marieront qu’en 1931, et une photo nous montre Joyce marchant, ce jour-là, au supplice. Nora est sa femme, soit, mais il la traite comme une maîtresse opaque, comme si elle commettait un adultère avec lui. Quand ils sont séparés, en 1909 (elle à Trieste, lui à Dublin, «ville d’échec, de rancœur, de malheur»), il lui écrit des lettres très folles mêlant l’adoration à la pornographie la plus crue. (“Joyce amoureux”, Le Nouvel Observateur, May 31, 2012)

State University of New York at Buffalo.

In 1988, Brenda Maddox who wrote a biography of Nora Barnacle (Nora: The Real Life of Molly Bloom, 1988) provided more details about the story of the passionate first meeting:

When a well-mannered, well-spoken, amusing and unthreatening young man stepped into her path one day in Dublin, therefore, Nora was quite happy to accept his invitation to meet him one evening. But she did not appear. Joyce took himself to the appointed place at the appointed time and waited until he gave up. A man more sure of himself with women would have gone round to the hotel to find out what had gone wrong. Joyce instead wrote Nora a letter. Its first words, ironically prophetic, convey the haze through which, even at 22, he peered at the world: 60 Shelbourne Road June 15, 1904

I may be blind. I looked for a long time at a head of reddish-brown hair and decided it was not yours. I went home quite dejected. I would like to make an appointment but it might not suit you. I hope you will be kind enough to make one with me – if you have not forgotten me! James A Joyce.

Nora had not forgotten him. Most probably she failed to keep the rendezvous because she could not get the evening off and had no way of letting him know. Once she had received his letter with his address, however, she was able to accept his second invitation.

Was the day of their first date Thursday, the 16th of June, 1904? Probably. That is the best that can be said. There is no evidence from letters or diaries that June 16 was the day that divided the lives of Nora Barnacle and James Joyce into before and after – none, apart from the date of the action of Ulysses.

To Richard Ellmann, Joyce’s biographer, the literary evidence that Nora and Joyce first walked out together on June 16 was overwhelming. “To set ’Ulysses’ on this date was Joyce’s most eloquent if indirect tribute to Nora,” says Ellmann. It was the day upon which “he entered into relation with the world around him and left behind him the loneliness he had felt since his mother’s death.” (“Joyce, Nora and The World Known to All Men”, May 15, 1988)

In The Paris Review, Jonathan Goldman shares his thought about the intriguing popular celebration of a notoriously difficult work of literature:

In the decade or so after Joyce’s death, in 1941, Bloomsday was instituted in Dublin; among the first participants were poet Patrick Kavanagh and novelist Flann O’Brien. The group role-played scenes of the novel. Around this time, references to Joyce began popping up in mainstream American culture, starting with Sunset Boulevard, with the novel usually deployed as a sign of elite literary culture and cachet. Perhaps the most famous sighting is the iconic photograph of Marilyn Monroe brandishing Ulysses, attempting to shed her bombshell reputation. Of course, this image plays on our questions of whether the novel is readable and whether anyone, much less a Hollywood star, actually reads it. These questions permeate the Ulysses legacy, but the answers hardly matter to the culture at large. Yes, many people read Ulysses (as Monroe apparently did), but, as our Bloomsday celebrations show, one need not penetrate the mystery in order to recognize, and partake of, its prestige. (“Bloomsday Explained” June 13, 2014)

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Literature

- Tagged: couple, Ireland, Joyce, love