An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

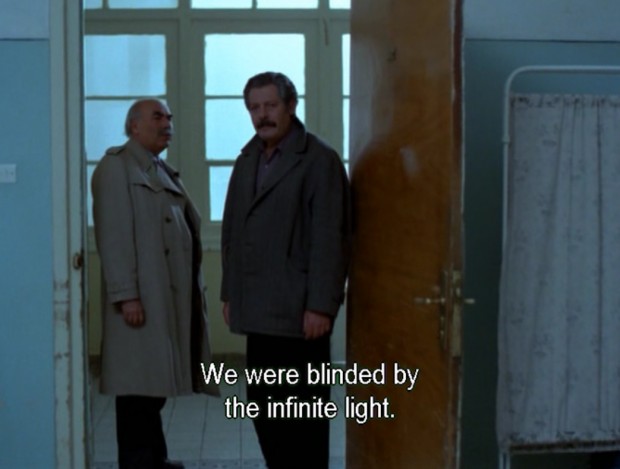

☛ The Beekeeper (Ο Μελισσοκόμος) by Theodoros Angelopoulos, Greece, 1986, screen capture at 01:52:57.

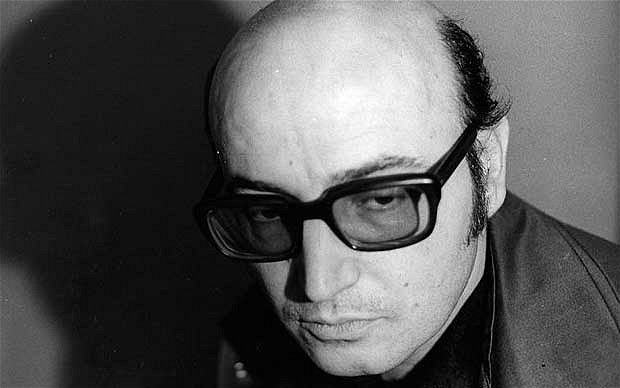

In the following lines I discuss a central episode from the film The Beekeeper and some general aspects of Angelopoulos’s style. At the end, I list relevant references about Angelopoulos’s films and the ways online media reacted to his death (obituaries).

• • •

The Beekeeper

When I learned about Angelopoulos’s death, I had just finished watching The Beekeeper for the second time. The film is about an aging man, husband and father, Spyros (played by Marcelo Mastroianni). The old man, visibly wearied by a long life, just retired from school teaching. For some reason, he seems to have lost touch with his family. His wife Maria and his son Aris do not understand him anymore. The only thing he cared about just escaped him: his youngest daughter got married and is leaving with her new husband, far away from the family home.

It’s springtime and the snow is melting away. Spyros is also a beekeeper. He has been for many years just like his father, and his grand-father before him. He must now take his beehives on the road, like every year, in search of flower fields further south.

On his way, he sometimes stops to meet colleagues and old friends. Early in the film, he picks up a young woman (Nadia Mourouzi) in need of a ride. She has no past and he, no future. Together, they’ll make an intense and difficult journey.

One night, in the middle of this journey, Spyros stops alone in a city to visit two long-time friends. One of them is sick and we find him lying in a hospital bed (he’s played by Serge Reggiani). They nonetheless sit and drink together, they share some laughters and some memories. They make plans to go walk by the beach at dawn and admire the sea.

They are unexpectedly interrupted by two nurses who came to check on the patient. Spyros and the third friend politely retire in order to give the man some privacy. In the doorway, Spyros suddenly stops. While he was being treated, his friend extended an arm and started knocking rhythmically with his knuckles on a nearby table. It’s Morse code. Spyros, still in the doorway with his friend, is the only one who’s able to understand what’s being communicated. He translates out loud:

The first time it was a sunny day

We were blinded by the infinite light

None of our desires was hidden

We were vainly looking for a shade

The little poem shared between friends acts like a spell attempting to resurrect a world which vanished in the mist of time. Although it’s been gone a long time already, they can’t help searching for a sign of it, in a perfume, a song, a landscape.

Maybe that’s what Spyros is looking for in the young hitchhiker he just met. He’s longing for her, but hopelessly because he understands, consciously or not, that she will never be able to give him back his youth. She can’t conjure up the time that went by already. He really has nothing significant to get from her. And yet he can’t help desiring her passionately ¹.

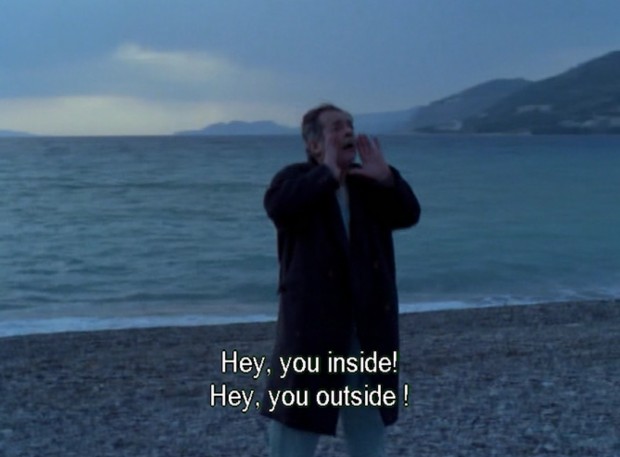

Later, the three men reunite again and go on the beach. The place is empty, it’s dawn and the the sun is about to come up. The sick man goes first to face the waves. He extends his arm and dances a little bit. He remembers how some other time, in the very same city, he and others had the opportunity to change history (most likely referring to his involvement in the Second World War).

Suddenly he turns back, facing the sleeping city and starts yelling: “Hey you! Hey you inside!”. He looks like he’s trying to wake the living from the slumber of their actuality. It feels like he needs to communicate the story of another time, a time that once existed when he too was present, well alive, full of dreams and hopes, constantly in action.

Nobody answers the repeated calls.

The film doesn’t end there. But this episode is emblematic of its main themes: love, despair, longing for lost paradises and failure to communicate.

• • •

Angelopoulos’s style

The cinema of Theo Angelopoulos is notorious for its extensive use of long takes and slow paced sequence shots (plan séquence in French). The Travelling Players (released in 1975) runs at about 230 minutes and is made of about 80 shots (see The Guardian: “Theo Angelopoulos: The Travelling Players” by Derek Malcolm, June 15, 2000). Therefore the “average shot length” is approximately 172 seconds per shot (roughly three minutes). For Angelopoulos’s film Eternity and a Day, the ASL is 114.3 seconds. In comparison, the ASL for The Bourne Ultimatum (2007) is around 2 seconds (for more information about ASL, see Cinemetrics; for a discussion about The Bourne Ultimatum’s fast pace, see David Bordwell “The unsteady Chronicle”, August 17, 2007). As an example of Angelopoulos’s style, here’s a four-and-a-half minutes sequence shot from the film Eternity and a Day which was the Cannes Film Festival Palme d’Or winner in 1998 (I did not chose it because it’s my favorite but because it’s the longest I could find on YouTube):

In an interview he did with Serge Toubiana and Frédéric Strauss back in 1988 he talks about his way of filming:

If I have to explain this, I would say that my preference for the long shot, the sequence shot, stems from my rejection of what is generally referred to as parallel editing, for I consider it fabricated. For historical reasons I accept the work of all those who resorted to this type of montage, like Eisenstein, but this is not my kind of cinema. In a certain manner, for me, each shot is a living thing, with a breath of his own, that consists of inhaling and exhaling. This is a process that cannot accept any interference; it must have a natural opening and fading. (Theo Angelopoulos: interviews, edited by Dan Fainaru, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001, p. 72)

If one adds the fact that his films are not always cheerful, often punctuated by long silences and shot against the bleak and rainy landscape of northern Greece (instead of the stereotypical settings of Greece’s sunny islands), one can understand why Angelopoulos’s work, despite numerous awards, were not always well received.

In April 1997, American critic Roger Ebert wrote of Ulysses’ Gaze (which has previously won the Special Jury Prize at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival):

Because it is a noble epic set amid the ruins of the Russian empire and the genocide of what was Yugoslavia, there is a temptation to give “Ulysses’ Gaze” the benefit of the doubt: To praise it for its vision, its daring, its courage, its great length. But I would not be able to look you in the eye if you went to see it, because how could I deny that it is a numbing bore? (“Ulysses’ Gaze” April 18, 1997)

Ebert went on to give the film one star (in comparison, he gave The Bourne Ultimatum three-and-a-half stars).

Is this another failure to communicate? Does Angelopoulos speak in Morse code? It seems the experience provided by his films echoed the themes he was preoccupied with during the years of his artistic practice. He speaks of another world, another time, and maybe also another cinema. His films use a language that has become unfamiliar to many of us. It’s not always easy to understand what he’s trying to say. In his essay on Angelopoulos, David Bordwell remarks:

Indeed, part of the fascination of Angelopoulos’s cinema is its almost naive anachronism. This filmmaker, so attuned to history (or History), so sensitive to post-Communist emigration and the war in the Balkans, appears unaware of how dated his artistic ambitions seem. (“Angelopoulos, or melancholy” in Figures traced in light: on cinematic staging, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, p. 140).

For some, this difficulty (if it’s experienced as such) will be enough to dismiss the man and all of his work. For others though, it will be a different experience. They will perceive something in one of Angelopoulos’s foggy and unsettling long sequence shots: fragments of a poetic message, a dizzying atmosphere, a new feeling (on Rotten Tomatoes Eternity and a Day scores at 90% with the audience and at 95% with the critics). Hopefully it will be enough of a reason to give the filmmaker a chance, to take a couple of hours in the solitude of a cinema and to try to understand parts of what he had to say. After all, what is there to gain from a journey devoid of any difficulties or obstacle?

• • •

References

- Theo Angelopoulos doesn’t have an official website: he has two. The first one (.gr) has been recently updated (Flash is required for some features). The home page has a note about the upcoming shooting of Angelopoulos new project The Other Sea (it now remains unfinished). Strangely enough this update was archived on January 24 of this year around noon. Angelopoulos died on the evening of the very same day. At the time of this writing, there’s no mention of his death on this website.

- There’s a second (.com) official Theo Angelopoulos website (Flash is required). At the time of this writing, it seems it hasn’t been updated since 2009. There’s no mention of the filmmaker’s death and it announces The Dust of Time as an “upcoming film” (it was released in early 2009). There’s also a page about The Beekeeper. On this page, one can read a quote from Angelopoulos about the signification of the last sequence of this particular film. The quote is not referenced: it comes from the interview Angelopoulos gave to Michel Ciment in 1987: Theo Angelopoulos: interviews, edited by Dan Fainaru, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001, p. 53.

- Until recently, some of Angelopoulos’ films, especially the earlier ones, were really hard to find and, when they were available, it was usually on VHS. On November 2011, European distributor Artificial Eye released The Theo Angelopoulos Collection Vol. 1. It includes all his feature films made before 1980: Reconstruction (1970), Days of ’36 (1972), The Travelling Player (1975) and The Hunters (1977). It’s a Region 2 DVD, but at least it’s out there. To my knowledge, none of his films exist on Blu-ray. A search on Amazon quickly shows the availability of his other films on DVD.

- David Bordwell’s essay “Angelopoulos, or melancholy” is really worth reading. The 10 first pages of the essay are available online at Google books. Right at the beginning of the essay, Bordwell “confess[es] [his] divided affection for [Angelopoulos’s] sprawling, majestic, irritating works.” He explains:

Certain of them (for example, Ulysses’ Gaze; Eternity and a Day, 1998) seem to me deeply flawed, inflating their thematic statement at the expense of narrative density. Others, such as The Travelling Player (1975) and The Hunters (1977), are remarkable accomplishments, but often they read better in critical commentary than they play on the screen. Four, however―Alexander the Great (1980), Voyage to Cythera (1983), Landscape in the Mist (1988) and The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)― seem to me authentic masterpieces, attaining grandeur without becoming grandiose. Still, none of the films lacks awe-inspiring passages, and all sustain, sometime brilliantly, that tradition of staging and shooting that is the concern of this book.

The introduction to Bordwell’s book is available on his official website.

- Andrew Horton is the Jeanne H Smith Professor of Film and Video Studies at the University of Oklahoma. He wrote two books about Theo Angelopoulos. Part of those books can be previewed online at Amazon: The Last Modernist: The Films of Theo Angelopoulos (Westport: Praeger, 1997; Amazon) and The Films of Theo Angelopoulos (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999; Amazon).

- Sense of Cinema has an excellent introductory article on Angelopoulos: it gives a general idea of his filmography along with a bibliography and additional web resources. See “Theo Angelopoulos” by Acquarello, issue 27, July-August 2003.

- As usual, MUBI offers an excellent round-up of relevant links about Angelopoulos: it’s a great place to start searching (I’ve referenced some of those links above). See “Theo Angelopoulos, 1935-2012” by David Hudson, January 24, 2012.

- [UPDATE – February 2, 2012] Catherine Grant’s web-archive Film Studies For Free offers around twenty links pointing to “high quality academic studies of his work, including a number of freely-accessible, book-length items”: see “Voyage to Cinema: Studies of the Work of Theo Angelopoulos” (Feb. 2, 2012).

- Obituaries in English:

- The New York Times: “Theo Angelopoulos, Greek Filmmaker, Dies at 76” by Margalit Fox, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

If Mr. Angelopoulos’s work was not universally known in the United States, the explanation could be found in his style, the antithesis of Hollywood studio fare.

Seen most often here on the art house circuit, his movies are dreamy, atmospheric and enigmatic. Many are allegories that illuminate the painful history of 20th-century Greece, from its occupation by the Nazis in World War II to its brutal civil war in the late 1940s.

Visually evocative, often beautiful, his films contain long sections with little or no dialogue. They are suffused with melancholy symbolism, all of it intensely personal and some of it intensely obscure. They are typically organized around very long takes that can assume the form of wordless meditations on space, as the camera pans slowly across a landscape. - The Telegraph probably produced the most interesting obituary about Theo Angelopoulos: “Theo Angelopoulos” January 26, 2012. Excerpt:

He was also much influenced by Michelangelo Antonioni, especially in his use of landscape to mirror the mood of a scene and of so-called “dead time”, when nothing is happening, yet the camera goes on filming even after the characters have walked out of the shot. He once said: “If I were asked to define my cinema, I would call it a cinema of dead spaces sandwiched between times in which things take place.”

- Another interesting obituary came from The Guardian: “Theo Angelopoulos obituary” by Ronald Bergan, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

The Greek film director Theo Angelopoulos, who has died aged 76 in a road accident, was an epic poet of the cinema, creating allegories of 20th-century Greek history and politics. He redefined the slow pan, the long take and tracking shots, of which he was a master. His stately, magisterial style and languidly unfolding narratives require some (ultimately rewarding) effort on the part of the spectator. “The sequence shot offers, as far as I’m concerned, much more freedom,” Angelopoulos explained. “By refusing to cut in the middle, I invite the spectator to better analyse the image I show him, and to focus, time and again, on the elements that he feels are the most significant in it.”

- Also from The Guardian an article exploring the theme of Incompleteness in Angelopoulos’s films: “Theo Angelopoulos: one last unfinished tale for chronicler of modern Greece” by Peter Bradshaw, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

Ultimately, Angelopoulos’s themes are the great themes of exile and return, and the equivalent interior, spiritual sense of alienation and longing for peace. They connect with another great Greek trope: the wanderings of Odysseus. Angelopoulos’s work was recurrently about this endless journeying towards a home receding over the horizon. Ulysses’s gaze was Angelopoulos’s gaze – long, steady and profoundly mysterious.

- The Washington Press used a press dispatch from The Associated Press: “Award-winning Greek filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos killed in road accident at age 76”, January 24, 2012.

- From Reuters: “Greek director Angelopoulos dies after accident during shooting” by Renee Maltezou and Ingrid Melander, January 25, 2012.

- The Hollywood Reporter: “Legendary Greek Filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos Dies”, January 25, 2012.

- Variety used the press dispatch from The Associated Press: “Theo Angelopoulos dies at 76”, January 24, 2012.

- The New York Times: “Theo Angelopoulos, Greek Filmmaker, Dies at 76” by Margalit Fox, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

- Obituaries in French:

- Le Monde, L’Express, Le Figaro and Libération first broke the news using the same press dispatch from AFP (Agence France Presse). Le Nouvel Observateur used a different press dispatch from AP (Associated Press).

- The following day Le Monde published a short article: “Theo Angelopoulos, l’éternité et une nuit” by Jacques Mandelbaum, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

Le tournant du XXe siècle, dont le cinéaste avait inscrit les convulsions dans le marbre, aura pu donner l’impression qu’Angelopoulos s’était éloigné de nous, ou que la marche de ce temps qui lui était si cher nous avait éloignés de lui. Ses films se faisaient plus rares, ils étaient reçus avec moins d’attention et de ferveur. On aurait pu croire qu’il était un homme du passé s’il n’avait préparé, au moment où la mort l’a cueilli, un film sur la crise en Grèce, et plus largement en Europe. Son titre était L’Autre Mer : il nous aurait sûrement surpris.

- Same thing with L’Express which published a short article the next day: “Cinq choses à savoir sur Theo Angelopoulos” by Thomas Baurez, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

C’est en 1980, que Theo Angelopoulos est définitivement identifié sur la carte du cinéma mondial. Son cinquième long-métrage Alexandre le Grand, l’histoire d’un bandit dans la Grèce du début du XXe siècle, est récompensé par la presse à la Mostra de Venise. Son Voyage à Cythère, oeuvre matricielle des films contemplatifs à venir, est célébré par cette même presse au festival de Cannes en 84. Il obtient en 88, le Lion d’Argent à Venise pour Paysage dans le brouillard, puis le Grand Prix au festival de Cannes pour Le regard d’Ulysse en 95. Enfin, c’est la consécration avec la Palme d’or pour L’éternité et un jour, film fleuve sur la fin d’un homme et plus sûrement d’un monde.

- Slate.fr also published an original article: “Théo Angelopoulos: l’éternité, un jour” by Jean-Michel Frodon, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

Prenant en charge la mémoire de son pays ravagé par les dictatures successives, la guerre civile, le massacre des résistants communistes, l’exil des Kapetanios survivants, l’impossible articulation d’engagements anciens et de contraintes nouvelles, Angelopoulos est l’un des cinéastes européens qui aura le plus attentivement pris en charge les grands bouleversements idéologiques de l’après-guerre, avec générosité et lucidité.

- Humanité has an original article: “Dernier voyage pour Theo Angelopoulos” January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

Théo Angélopoulos a marqué l’histoire du cinéma européen, après avoir fait émerger un “nouveau cinéma grec” dans les années 70 à la chute du régime des colonels, pétri de lenteurs et de méditations pour raconter les blessures de la Grèce et de l’humanité. “Peut-être que c’est triste, mais mon ancêtre Aristote disait que la mélancolie est la source de la création”, disait-il en 1999 lors de sa leçon de cinéma au festival de Cannes, un an après y avoir reçu la Palme d’Or pour son film L’éternité et un jour, un long-métrage en forme de réflexion sur la mort.

- Serge Kaganski wrote a small piece for Les Inrocks: “La mort du cinéaste grec Theo Angelopoulos”, January 25, 2012. Excerpt:

Mais tout n’est pas perdu pour les Grecs : en disparaissant, Angelopoulos laisse derrière lui une nouvelle vague prometteuse incarnée par les jeunes et fougueux Yorgos Lantimos, Athina Rachel Tsangari ou Panos Koutras.

The best Greek film I’ve seen recently is Dog Tooth by Yorgos Lantimos (IMDb).

Previously on Aphelis: “Greek Director Michael Cacoyannis Dies at 90 (1921-2011)” and “Proust : les paradis qu’on a perdus / paradises we have lost”

• • •

¹ Perhaps it will be adequate here to add a note about the “eros of melancholy”. Spyros is emblematic of a certain description of the melancholic disposition. See for example Giorgio Agamben’s Stanzas:

[…] it might be said that the withdrawal of melancholic libido has no other purpose than to make viable an appropriation in a situation in which none is really possible. From this point of view, melancholy would be not so much the regressive reaction to the loss of the love objects as the imaginative capacity to make an unobtainable object appear as if lost. If the libido behave as if a loss had occurred although nothing has in fact been lost, this is because the libido stages a simulation where what cannot be lost because it has never been possessed appears as lost, and what could never be possessed because it had never perhaps existed may be appropriated insofar as it is lost. (Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, tr. by Ronald L. Martinez, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, [1977]1993, p. 20)

The key point of this hypothesis lies in the idea that the melancholic disposition is possible because nothing was lost in the first place. Spyros thinks he is longing for his youth or for some other object of desire from his past. However, it’s more than likely that he’s essentially longing not for things as they were, but for the constructed memory he now has of them. What he wants belongs to the order of the phantasm: one cannot (re)possess a phantasm. However, one can imagine the phantasm as something lost, out of reach, and then appropriately long for it. That way ―even if it’s a paradoxical way― a person can enjoy something she never had in the first place. In this view, melancholy can be understood as a tortuous workaround to the object of desire. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication

- Tagged: Angelopoulos, beekeeper, death, Greece, history, love, melancholy, memory, obituary, time