An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

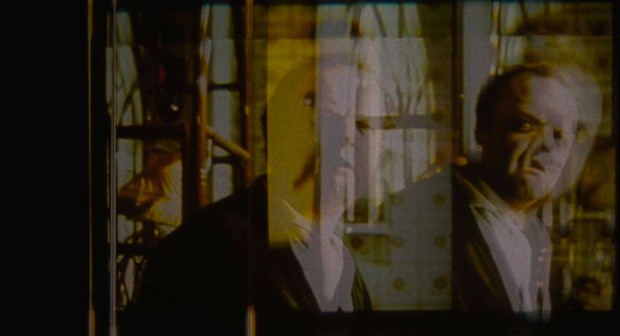

☛ Berberian Sound Studio by Peter Strickland, United Kingdom, 2012 (IMDb). Still @ 01h 20m.

In his Prolegomena (Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können, 1783), Kant wrote of analogies:

Such a cognition is one of analogy, and does not signify (as is commonly understood) an imperfect similarity of two things, but a perfect similarity of relations between two quite dissimilar things. (§58; 1902 trans. by Paul Carus, revised by James Fieser, 1997)

The protagonist of Berberian Sound Studio could be said to be immersed in analogies. Gilderoy (convincly played by Toby Jones) is a sound engineer and foley artist who just got himself a contract with an Italian studio.

There is only but a few minutes of exterior shots in the film, and even those few minutes could be subject to some debate. For the most part, it takes place in a windowless studio and some other rooms, where the outside is not perceptible either.

There, Gilderoy will be enlisted to work on a project he was not quite expecting. He spends his days adjusting potentiometers, watching trembling dials and rewinding magnetic tapes. The sound effects themselves are produced in the old fashion way.

Watching a screen where reels of 35mm film are being projected, the foley artist waits for his cue. At the opportune moment, he slices melons, rattles chains or shakes a cabbage in a pool of water. Layers upon layers of such sound effects are mixed with lines of dialogue and ambient music. The results are just as intricate as the cue sheets that are being used in the process.

Instead of circulating in an extended landscape, the protagonist is progressively absorbed in the increasing intensity of an analogical soundscape. This is not without raising a perplexing issue. Not unlike the Architect in Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010), the sound engineer is actually piecing together the environment he his, at the same time, experiencing.

This soundscape gradually bridges the perceived gap between reality and fiction. The sound studio and the film he’s working on may very well be “two quite dissimilar things”, but through painstaking sessions of sound editing, they progressively grow strong similarity of relations.

Such similarities increase until the sound editor becomes “alienated in analogies”, to borrow from Michel Foucault (previously). Like acetate film under excessive heat, differences finally melt, allowing reality and fiction to engulf one another.