An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

A long time ago I made the decision to keep out of my country’s politics. As I tried to explain on another occasion, this did not mean at all that I was indifferent to our political life.

So, from that time until now I have refrained, as a rule, from touching on matters of that kind. Besides, all that I published up to the beginning of 1967 and my stance thereafter (I haven’t published anything in Greece since freedom was gagged) have shown clearly enough, I believe, my thinking.

Nevertheless, for months now I have felt, inside myself and around me, with increasing intensity, the obligation to speak out about our current situation. With all possible brevity, this is what I would say:

It has been almost two years now that a regime has been imposed on us which is totally inimical to the ideals for which our world — and our people so resplendently — fought during the last world war.

It is a state of enforced torpor in which all those intellectual values that we succeeded in keeping alive, with agony and labor, are about to sink into swampy stagnant waters. It wouldn’t be difficult for me to understand how damage of this kind would not count for much with certain people. Unfortunately, this isn’t the only danger in question.

Everyone has been taught and knows by now that in the case of dictatorial regimes the beginning may seem easy, but tragedy awaits, inevitably, in the end. The drama of this ending torments us, consciously or unconsciously — as in the immemorial choruses of Aeschylus. The longer the anomaly remains, the more the evil grows.

I am a man without any political affiliation, and I can therefore speak without fear or passion. I see ahead of me the precipice toward which the oppression that has shrouded the country is leading us. This anomaly must stop. It is a national imperative.

Now I return to silence. I pray to God not to bring upon me a similar need to speak out again.

☛ Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 58, no. 3, 1996-1997, p. 591: “This is George Seferis’s statement denouncing the Colonels’ regime. [The English translation by Edmund Keeley] is based on a carbon copy of the original in the Selected Papers of George Seferis, Manuscripts Division, Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library”. PDF.

On April 21, 1967, there was a coup d’état in Greece lead by colonels. They overthrew the interim government in place at the time and prevented general elections scheduled for May 28 of the same year. This right-wing military dictatorship lasted for seven long years, from 1967 to 1974. It came to be known as “The Regime of the Colonels”, “The Junta” or alternatively “The Seven Year”.

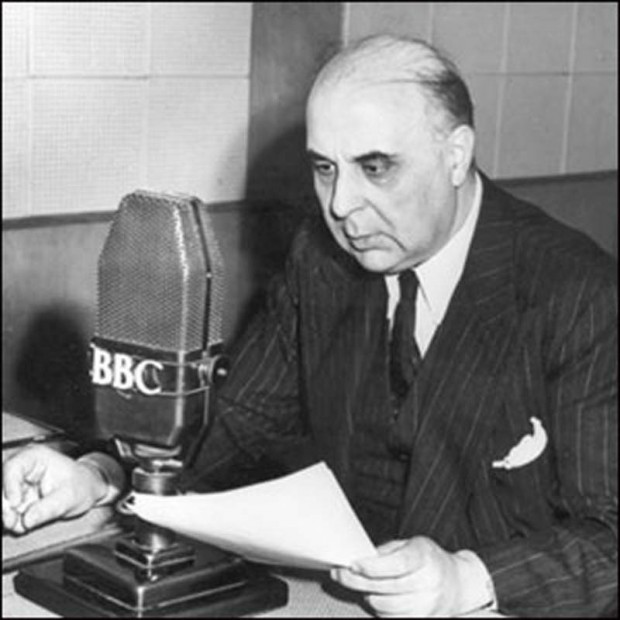

George Seferis (1900-1971) was at the time one of the most renowned Greek poet. He was also well known internationally since he received the Nobel Prize for literature, in 1963. He was not perceived as a political figure, but the situation in Greece was certainly unbearable for him. On March 28, 1969 he broke his silence and, with the help of the BBC World Service, he broadcast the short but galvanizing message translated above. His statement was later reprinted by several newspaper in Athens.

The urgent and firm conclusion of his speech ―”This anomaly must stop”― could certainly be interpreted by some today as a valid program to address new crisis. Indeed, the word Seferis used –η ανωμαλία, “the anomaly”– means “uneven”, “unequal”, “unregular” (from privative αν and ὁμαλός “smooth”, “even”: see ἀνώμαλος in A Greek-English Lexicon by Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott).The plutocracy which some view as the root of debt crisis in Greece or the difference in wealth between the 1% and the 99% at the origin of the Occupy Wall Street movement are, properly speaking, anomalies.

I found out about Seferis’ declaration while watching the excellent documentary Greece: The Seven Black Years directed for the BBC by award-winning British documentary filmmaker Mischa Scorer (IMDb). The film was shot in 1974 and first broadcast by the BBC on April 29, 1975, nearly eight years days for days after the Colonels took over.

The documentary is about “living in Greece during the colonels’ regime”. It depicts testimonies by Greek citizens after the democracy was restored, but also historical (and poignant) archival footage. The film documents, among other things, the heroic and tragic students uprising at the Athens Polytechnic, which help to a certain extent to topple the dictatorship (see Wikipedia: “Athens Polytechnic uprising”). It also features an excerpt form Seferis’ declaration (read off-camera in another English translation).

If I’m not mistaken, this documentary was not available online until a few days ago. It was dug out of the BBC archives and posted online by Adam Curtis. Curtis is also a renowned British documentarist. Among other things, he directed The Century of the Self in 2002 (watch it at the Internet Archive) and All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace in 2011 (watch it at Top Documentary Films). For more about Adam Curtis, see his Wikipedia and IMDb pages.

In a post titled “The Ghost of the Colonels” and published on his blog on Nov. 3, 2011, Adam Curtis had the good idea to try to understand the Greece debt crisis ―and especially the possibility of a referendum― by stepping back in time and study Greece recent history:

In the present crisis over Greece there is a furious argument about whether the Greek people should be allowed to vote on the proposed solution. Many of the voices against this come from the world of finance and economics. They say that the crisis is too dangerous to leave to the will of the people.

I just wanted to show why some Greek politicians – and especially George Papandreou, even though he may have retreated from a referendum – might think it important to allow the people a voice. […]

The discussion of Greece today in the press and the political offices of Europe is almost completely ahistorical – everything is couched in utilitarian terms of economic management. I just think it is important to put the present crisis in a wider historical context. Above all the extraordinary history of the military dictatorship and the savage effects it had on the whole of Greek society.

He goes on presenting the documentary Greece: The Seven Black Years” as well as a “short compilation of some of the best bits of the news coverage from the time”. Those are priceless documents for anyone interested in Greece history (past and present) or in civil uprisings. Both videos must be watch on the BBC website or downloaded and watch with the help of BBC iPlayer (in both scenario, Flash is required; see BBC iPlayer Help for more information).

Below are more online resources about George Seferis and his Declaration of 1969:

- BBC Ελληνική has an audio recording of Seferis reading his declaration in Greek: “Η δήλωση του Σεφέρη κατά της χούντας στην Ελλάδα (1969)” (George Seferis’ Declaration of March 28, 1969 against the junta in Greece). Real Player is needed in order to play the file. Alternatively, one can also listen to Seferis reading his Declaration on YouTube. The text (in Greek) can be found here (it’s a webpage created by two students of the 14th Gymnasium of Peristeri).

- Webtopos is a website curated by Katarina Sarri, a Greek piano player. Among other things, she compiled a rich collection of links and facts about George Seferis. It’s a great place to start a research online about him.

- From the Journal of European Studies: “George Seferis and Dictatorship” by George Dandoulakis (June 1989 vol. 19 no. 2 135-147, PDF)

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: anomaly, crowd, democracy, dictatorship, freedom, Greece, Occupy Wall Street, power, protest, Seferis, uprising