An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Network directed by Sidney Lumet, written by Paddy Chayefsky, United-States, 1976, excerpt at 1:34:27. In the script version from January 14, 1976, pp. 125-127. IMDb.

[UPDATE–Oct. 8th, 2014] This essay was translated into Persian for the Zamaneh Tribune, hosted by Radio Zamaneh: see “جهان یک تجارت است: سرمایهداریِ مسیحائیِ آرتور جِنسِن”. Founded in 2005, Radio Zamaneh is based in Amsterdam. It provides independent journalism to Iranian and Persian-speaking communities about present day issues (learn more about it). My warmest thanks to Masoomeh Raisi for this translation.

• • •

The on-air rants of TV anchorman Howard Beale (Peter Finch) calling “bullshit” on everything and declaring to be “mad as hell” are legendary. The quote “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” is 19th in AFI’S 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes list. Peter Finch was posthumously awarded the Best Actor Oscar for his performance. As one of the characters, played by Faye Dunaway, later explains in the film:

Howard Beale got up there last night and said what every American feels ― that he’s tired of all the bullshit. He’s articulating the popular rage. (Network script, 1976: 45)

Many of the themes explored by the film are still highly relevant today. For example, the Occupy Wall Street protest movement expressed similar sentiments of rage and disappointment in the way things are going. In fact, for a brief moment in the fall of 2011, the sign “Shit Is Fucked Up And Bullshit” caught up in popularity. I’ll come back to it.

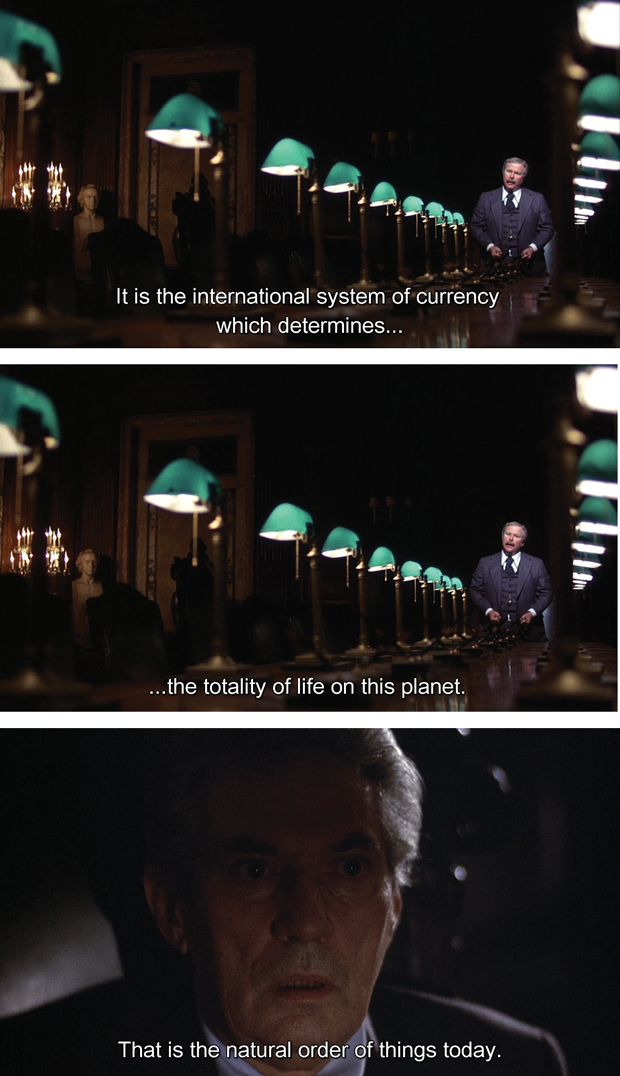

In the dark comedy that is Network, Howard Beale’s dissatisfaction is provided with a cynical answer. Upon learning about his on-air rants, the chairman of the company for which Beale works, Arthur Jensen, invites him for a private meeting in a darkened boardroom. The perspective and lighting of the sequence that follows enhance its dramatic effect, to the point it borders on caricature. In this setting the chairman ―convincingly played by Ned Beatty― delivers a mesmerizing, sermon-like speech (see it on YouTube; Filmsite.org hosts the audio clip). He eloquently explains to a bewildered Beale that there is, in fact, an order and a logic to everything: the order is called business and its logic is the logic of the all-encompassing flow of currencies.

The present commentary is concerned with this noteworthy speech. Specifically, it addresses four propositions made by Arthur Jensen during his harangue to Howard Beale: there are no nations, everything is currency, the world is a business and, finally, everyone can participate.

All the speech excerpts are quoted from a version of Chayefsky’s script revised on January 14, 1976. This script is available both on Screenplays for You and as a PDF file. The page numbers in the quotes I use refer to this file. Additional references pertaining to the Occupy Wall Street sign “Shit Is Fucked Up And Bullshit” are provided at the end.

• • •

• There are no nations

JENSEN–You are an old man who thinks in terms of nations and peoples. There are no nations! There are no peoples! There are no Russians. There are no Arabs! There are no third worlds! There is no West! There is only one holistic system of systems, one vast and immane, interwoven, interacting, multi-variate, multi-national dominion of dollars! petro-dollars, electro-dollars, multi-dollars!, Reichmarks, rubles, rin, pounds and shekels! (Network script, 1976: 126)

When Arthur Jensen claims “There are no nations!” he is echoing an observation made by various analysts during the 20th century. The idea that modernity is characterized by a crisis (or a fragmentation) of the nation-state as the traditional political form fueled a significant part of Carl Schmitt’s work, from The Concept of the Political (1932) to Theory of the Partisan (1962). As Giorgio Agamben has shown, the problem is intimately linked to notions of sovereignty and political exception1.

Although it does not explicitly address the concept of “nation”, Antonio Gramsci’s brief remark about the “Crisis of Authority” in his Quaderni del carcere tackles a similar problem. This is not only because Gramsci thinks the crisis relates to a state of exception ―which he calls “the interregnum”―, but because he also links the crisis to an economical factor: a “wave of materialism”2. In his speech, chairman Arthur Jensen clearly suggests nations have been replaced by a single global market (see below “The world is a business”).

Zygmunt Bauman has been exploring the idea that the crisis of modernity is linked to the “eroding” or “fading” of the nation-state for quite some time3. Recently, he has proposed a follow-up to Gramsci’s ideas in an essay titled “Times of interregnum”. In it, he explains how the market participates in breaking down the “triune principle of territory, state, and nation”:

Ever rising numbers of competitors for sovereignty outgrow already, even if not singly then surely severally, the power of an average nation-state. Multinational financial, industrial, and trade companies account now, according to John Gray, ‘for about a third of world output and two-thirds of world trade’. Sovereignty, which right to decide the laws as well as the exceptions to their application, along with the power to render both decisions binding and effective, is for any given territory and any given aspect of life-setting scattered between multiplicity of centers and, for that reason, eminently questionable and open to contest; while no decision-making agency is able to plea full (that is, unconstrained, indivisible, and unshared) sovereignty, let alone to claim it credibly and effectively.4

In a short, 7-minute video he recorded in 2011 for the Ten Years of Terror project, conceived by Brad Evans and Simon Critchley, Bauman creates an allegory to illustrate the depth of the current crisis. In his allegory, we are all passengers on an airplane. In the middle of the flight, an automatic announcement reveals that the cabin is empty: the plane is without pilots. Worst, it appears to be heading to an airport that has not been built yet: in fact it is still on the drawing board. Not only are we not in control, but nobody is and there seems to be nothing we can do about it. For Bauman, the essential reason for this feeling of powerlessness lies in the divorce between power and politics, between the ability to have things done and the ability to decide which things have to be done. Up until half a century ago, power and politics were united in the nation-state. In recent times however, power has escaped local forms of government and evaporated into growing global networks of interests.

Simon Critchley borrowed both Bauman’s allegory and argument for a lecture5 he first gave as keynote speaker at the 2012 Neil Postman Graduate Conference themed, that year, Thinking Through Collapse. Incidentally, Critchley picked the Occupy Wall Street sign mentioned above for the title of his keynote lecture “Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit” (watch it on Vimeo).

For Critchley, this sign perfectly illustrates Bauman’s point. It expresses both the general belief that something in the actual state of affairs is quite wrong, and the feeling of being fed up, even though or especially as one cannot precisely pinpoint why.

• People as currency

JENSEN―It is the international system of currency that determines the totality of life on this planet! That is the natural order of things today! That is the atomic, subatomic and galactic structure of things today! (Network script, 1976: 126)

According to Arthur Jensen, not only there are no nations, but there are no peoples as well. There is but one thing: an ubiquitous “system of currency”. One way to understand this is to understand people as currency, that is as “living currency”, to borrow from Pierre Klossowski’s book La monnaie vivante6. Without diving into the details of Klossowski’s short but dense essay, there are ways to quickly illustrate the relevance of this view.

One such way is to consider recent financial transactions involving notorious social media companies such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Facebook went public on May 18, 2012 (NASDAQ:FB). As of Nov. 10, 2013, its market capitalization was evaluated at $115.75B ($47.53/share). Twitter went public on November 7, 2013 (NYSE:TWTR). Three days later, its market capitalization was evaluated at $19.68B ($41.65/share). As for Instagram, it was bought by Facebook on April 9, 2012 for $1B. In each of those cases, and in many more similar cases, the financial value of a given company is intimately linked to the number of users said company is able to mobilize or to engage. Those users are worth money for various reasons. Among other things, they are perceived as potential consumers who can be solicited through the company’s online service (by means of advertisement, for example). Advertisers are willing to buy information gathered by an online service provider regarding users’s preferences and online habits.

Another example of living currency ―or “biocurrency”― is offered by the new entrepreneurial venture Miinome (still in beta):

The Minneapolis-based venture is developing a platform through which its customers will eventually be able to cash in on the value of their DNA by selling their genetic data to marketers and researchers; they’ll also be able to control which genetics-based offers they receive.7

One thing this last example helps to emphasize is that in all those examples, the user is also a commodity: his time, his attention or his DNA circulates on the market. He or she can be sold or bought as a commodity just as he or she can also be used as a medium of exchange. Although commodity and money are usually distinguished from one another, there are cases where the distinction is blurred. In all the examples above, the user is a “commodity money”. A famous example of commodity money is the exchange of cigarettes between prisoners in war camps8.

But one doesn’t have to spend his day on Facebook or sell his DNA to become a commodity money. What Klossowski’s essay shows, among other things, is how wage-based labour transforms any human being into an “industrial slave”, reminding us in the process that the slave is a paradigmatic example of a living commodity money.

• The world is a business

There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and A T and T and Dupont, Dow, Union Carbide and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today. What do you think the Russians talk about in their councils of state ― Karl Marx? They pull out their linear programming charts, statistical decision theories and minimax solutions and compute the price-cost probabilities of their transactions and investments just like we do. We no longer live in a world of nations and ideologies, Mr. Beale. The world is a college of corporations, inexorably determined by the immutable by-laws of business. The world is a business, Mr. Beale! (Network script, 1976: 127)

Along with nations, democracy as a political mode of coexistence is also being challenged by the erosion of the nation-state and the “currencification” of everything (see previously here and here). As Arthur Jensen explains to Howard Beale, there is no replacement for democracy: the only thing left to enforce law and order is business.

A similar point was made recently in the movie Killing Them Softly (2012; IMDb), although the intention this time was not to convey it through a cynical caricature, but to lay it down in a much more solemn manner. The final scene of the film is set in a bar. In the background, a television set is broadcasting Barack Obama’s Victory Speech (watch it). At one point, Obama is heard saying “… to reclaim the American dream and reaffirm that fundamental truth, that, out of many, we are one…”. Upon hearing this, Jackie Cogan (Brad Pitt) tells the man with whom he’s supposed to be doing a transaction that the “One People” thing is nothing but a myth created by Thomas Jefferson. He goes on:

My friend, Thomas Jefferson is an American saint because he wrote the words ‘All men are created equal’, words he clearly didn’t believe since he allowed his own children to live in slavery. He’s a rich white snob who’s sick of paying taxes to the Brits. So, yeah, he writes some lovely words and aroused the rabble and they went and died for those words while he sat back and drank his wine and fucked his slave girl. This guy wants to tell me we’re living in a community? Don’t make me laugh. I’m living in America, and in America you’re on your own. America’s not a country. It’s just a business. Now fuckin’ pay me.

The ideal of the harmonious, if not unanimous, communio precedes Thomas Jefferson by a couple of centuries. It was already present in Paul’s writing, while Saint-Augustin made it one of the very first of his rules regarding life in common. The folkloric belief about the word “community” being rooted in the etymology com + unus likely comes from his work. The Christian tradition may have been inspired, in turn, by the ancient principles of the Pythagorean κοίνονια.

The argument made in Killing Them Softly is that reality doesn’t seem to agree with the ideal of this communal bond. “E pluribus unum” makes for a nice motto, but Jackie Cogan seems to believe America’s social contract is failing. In an interview she made in 1973, Hannah Arendt insisted on the particularity of this contractual bond in the United-States:

This is not a nation-state, America is not a nation-state. Europeans are having a hard time understanding this simple fact. […] This country is united neither by heritage, nor by memory, nor soil, nor by language […] There are no “native” Americans, except of course for the Indians. Everyone else is citizens and those citizens are united by one thing only, which is a lot, and that is one becomes a citizen of the United States by accepting its Constitution. (my transcription, with the help of the French translation).

Instead of a social contract, Jackie Cogan intends to rely on business to keep things relatively under control. The situation depicted by Arthur Jensen in Network is a bit different. The picture he draws for the benefit of Howard Beale is much more enthusiastic, inflated with heavy messianic tones. Contrary to Jackie Cogan, chairman Arthur Jensen has not abandoned the ideal of community. Instead, he intends to realize it as business model.

• Everyone can participate

JENSEN–It has been since man crawled out of the slime, and our children, Mr. Beale, will live to see that perfect world in which there is no war and famine, oppression and brutality ― one vast and ecumenical holding company, for whom all men will work to serve a common profit, in which all men will hold a share of stock, all necessities provided, all anxieties tranquilized, all boredom amused. (Network script, 1976: 127)

As I suggested above, the ideal of participation finds its root in religious traditions, something explicitly acknowledged both in Arthur Jensen’s speech and in the movie in general. Here however, Jensen seems to suggest people will be able to share part of the profit generated by the global market. Since the 70’s, the promise made to the living currency to the effect it would eventually share a part of the “common profit” has not quite come to reality. Instead, it has led to the making of what Maurizio Lazzarato has called “the indebted man”:

The subjective achievements neoliberalism had promised (“everyone a shareholder, everyone an owner, everyone an entrepreneur”) have plunged us into the existential condition of the indebted man, at once responsible and guilty for his particular fate.9

Years earlier, Walter Benjamin already took note of the religious dimension of capitalism and drew attention to the central function played by guilt:

Capitalism is probably the first instance of a cult that creates guilt, not atonement. In this respect, this religious system is caught up in the headlong rush of a larger movement. A vast sense of guilt that is unable to find relief seizes on the cult, not to atone for this guilt but to make it universal (…).10

In his comment, Benjamin underlines “the demonic ambiguity” of the concept of guilt which, in German (Schuld), signifies both guilt and debt. This observation was first developed by Nietzsche in the second dissertation of his On the Genealogy of Morals: “Guilt, Bad Conscience, and Related Matters”.

Two temporary conclusions can be drawn for those remarks. First, that when it comes to the world as a business, participation is not about redemption, but about the growth of everyone’s debt/guilt. “Capitalism”, wrote Benjamin, “is entirely without precedent, in that it is a religion which offers not the reform of existence but its complete destruction.” (Ibid.: 289)

Second, as the movie suggests, participation is all inclusive: in the global market, everyone participates to its expansion, even those who are against it. This is, after all, the allegory offered by Howard Beale. For even when he is vehemently denouncing the “bullshit” on air, he is in fact participating to its effervescence and its growth (measure in audience share). In Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis, a character comments about a crowd of protestors:

The market culture is total. It breeds these men and women. They are necessary to the system they despise. They give it energy and definition. They are market-driven. They are traded on the markets of the world. This is why they exist, to invigorate and perpetuate the system.11

Arthur Jensen insists: this system of currency is the totality of life, it is the natural order of things. There is no outside to the global market. It is the milieu in which we are all embedded, all together in debt, and all guilty as one.

• • •

• About the Occupy Wall Street sign “Shit Is Fucked Up And Bullshit”

Although it would be hard to determine with precision where the slogan “Shit Is Fucked Up And Bullshit” originated (see Google Trends), it is possible to document how it spreads, up to a certain extent.

On the first day of Occupy Wall Street, September 17, 2011, a girl wearing a t-shirt where the slogan had been hand-sprayed (using a stencil) was photographed in Zuccotti Park. The same day, a young man holding a sign with the same slogan was also photographed.

The young man holding the sign calls himself Mickey Smith (Facebook, Twitter). In the fall of 2011, he was photographed on a number of occasions, always holding the same sign, sometimes giving an interview (Flickr, Google Images).

On October 1st, The Gothamist published a gallery of photos by Sam Horine titled: “Photos: The Faces Of Occupy Wall Street”. Photo no. 15 shows Mickey Smith holding his sign. A few days later, the photo was picked up by BuzzFeed and republished in a post titled “The 50 Best Signs From #OccupyWallStreet”. Months later, in March of 2012, the same photo was used for the design of the poster of the 2012 Neil Postman Graduate Conference, featuring Simon Critchley’s keynote lecture titled “Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit”.

On October 14, a photo taken by Flickr user jamie nyc showing only the Smith’s sign, was featured on Real Time with Bill Maher (Season 9, Episode 31). The same day, Smith tweeted: “Shit is fucked up and bullshit, I can’t believe a started a thing #occupywallst #ows #SIFUABS”.

In the Fall of 2011, the sign was also mentioned in The New Republic and The New Yorker. McKenzie Wark published a paper in Theory & Event titled “This Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit” (supplement, Volume 14, Issue 4, 2011). In it, he directly commented a sign bearing the (now) famous slogan:

Everybody knows. It was so articulately put by the person at Occupy Wall Street whose sign read: THIS SHIT IS FUCKED UP AND BULLSHIT. We know it’s broken; we know the sock puppets have nothing to say. What has to frankly be described as a neo-fascist backlash was already underway even before Occupy Wall Street began. It can only intensify.

In March of 2012, New York artist Sebastian Errazuriz debuted his Occupy Chairs installation at the VIP opening of the Armory Show (NYC). One of the item in the series prominently features the slogan “Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit”.

Mickey Smith now sells a t-shirt with the slogan printed on it. Other merchandises can be bought online as well.

• • •

1. The State of Exception, tr. by Kevin Attell, Chicag: The University of Chicago Press, [2003] 2005. ↩︎︎

2. Selections From The Prison Notebooks, edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith, New York: International Publishers, [1971] 1992, pp. 275-276. ↩︎︎

3. See for example Globalization (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998, p. 55: Chapter 3 – “After the Nation-state ― What?”); Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000, p. 185: “Community. After the nation-state”); Society Under Siege (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002, p. 1-22:“Introduction”); Collateral Damage: Social Inequalities in a Global Age (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011, “From the agora to the marketplace”, esp. pp. 22-27). ↩︎︎

4. “Times of interregnum”, Ethics & Global Politics, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2012, p. 50; this essay was included in Bauman’s book 44 Letters From the Liquid Modern World, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010: pp. 119-122. ↩︎︎

5. Simon Critchley first gave a lecture titled “Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit” at the Neil Postman Graduate Conference on March 23, 2012. A version of the first 30 minutes of this lecture was published in the print edition of Adbusters Magazine no. 101 (May/June 2012): “Occupy’s Perfect Storm” (it was posted on Adbuster website on April 16, 2012). Critchley delivered the same lecture at the ICI Berlin Institute, on June 28, 2012. This time, it was titled “SHITISFUCKEDUPANDBULLSHIT. A short discourse on the consequences of the separation of power and politics”. It’s also available on YouTube. ↩︎︎

6. Paris: Rivage poche/Petite Bibliothèque, [1970] 1994. An independent English translation is available on Scribd. Another English translation is apparently on its way. ↩︎︎

7. Minnesota Business Magazine: “Q+A: Miinome CEO Paul Saarinen on genetics-based marketing” by Tom Johnson, March 16, 2013. ↩︎︎

8. The classic study of this phenomenon is R. A. Radford’s essay “The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp”, Economica, New Series, Vol. 12, No. 48, Nov., 1945. ↩︎︎

9. The Making of the Indebted Man, tr. by Joshua David Jordan, Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), [2011]2012, p. 8. ↩︎︎

10. “Capitalism as Religion” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Vol. 1 1913 – 1926, ed. by Michael W. Jennings, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 288. ↩︎︎

11. New York: Scribner, 2003, p. 90. ↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Movies

- Tagged: Bauman, Benjamin, biopolitics, capitalism, community, debt, democracy, economy, globalization, Gramsci, Klossowski, Lazzarato, nation, nation-state, people, politics, power, religion, sovereignty, state, world