An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

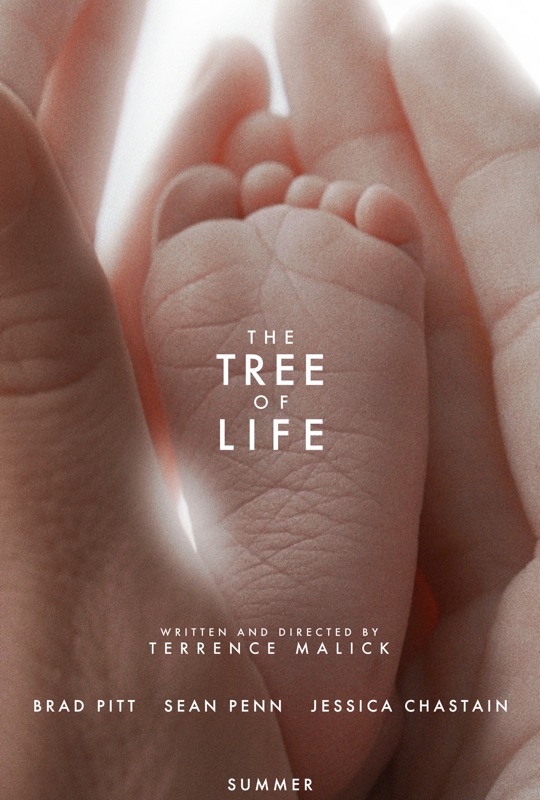

U.S. director Terrence Malick won the Palme d’Or for best picture at the Cannes film festival on Sunday for “The Tree of Life,” a meditative, metaphysical epic starring Brad Pitt and Sean Penn.

Only his fifth feature, the contemplation on the origins of life and where we go when we die was among the firm favorites to walk off with the coveted award, one of the most prized in the movie calendar after the Oscars.

☛ Reuters: “Terrence Malick epic wins Palme d’Or in Cannes”, May 22, 2011

More online resources about The Tree of Life and director Terrence Malick:

- Fox Searchlight’s official website for The Tree of Life. Flash is required.

- Below is the official HD trailer for The Tree of Life (uploaded by Fox Searchlight on December 10, 2010). The official description goes like this:

From Terrence Malick, the acclaimed director of such classic films as BADLANDS, DAYS OF HEAVEN and THE THIN RED LINE, THE TREE OF LIFE is the impressionistic story of a Midwestern family in the 1950’s. The film follows the life journey of the eldest son, Jack, through the innocence of childhood to his disillusioned adult years as he tries to reconcile a complicated relationship with his father (Brad Pitt). Jack (played as an adult by Sean Penn) finds himself a lost soul in the modern world, seeking answers to the origins and meaning of life while questioning the existence of faith. Through Malick’s signature imagery, we see how both brute nature and spiritual grace shape not only our lives as individuals and families, but all life.

- The official page for The Tree of Life at the Cannes Festival website (where you can download its official press kit: PDF).

- List of all awards for the 2011 edition of the Cannes International Film Festival.

- Terrence Mallick once translated Heidegger’s essay Vom Wesen des Grundes (written in 1928, published in 1929 in Festschrift für Edmund Husserl zum 70, by M. Niemeyer in Halle a. d. Saale / Google Books) as The Essence of Reasons (Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1969). Another translation by William McNeil is available in Pathmarks (Cambridge University Press, 1998). In the official collection of Heidegger’s complete works, the Gesamtausgabe (an ongoing project), “The Essence of Reasons” is listed as number GA9. In French the essay was translated as “Ce qui fait l’être-essentiel d’un fondement ou ‘raison'” (in Question I et II, trad. H. Corbin, Gallimard, Paris, 1972, pp. 85-158 / Amazon).

- From the online film publication Rouge: “The Cinema of Terrence Malick” by Adrian Martin (December 2006)

- From Film-Philosophy: “Calm – On Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line“ by Simon Critchley (Vol. 6, No. 1, 2002). For this essay, the author was able to get the collaboration of Nick Bunnin, Stanley Cavell, Jim Conant, Hubert Dreyfus, and Jim Hopkins. The first paragraph reads as follow:

- From Vertigo: “Terrence Malick’s Heideggerian Cinema. War and the Question of Being in The Thin Red Line” by Marc Furstenau & Leslie MacAvoy (Vol. 2, No. 5, Summer 2003 / PDF):

- From Sense of Cinema: “Terrence Malick” by Hwanhee Lee (Issue 23):

- From The Walrus: “The Promise of Beauty. Terrence Malick’s brave new worlds” by Pico Iyer, September 2006:

- From nonsite.org: “Terrence Malick’s New World” Richard Neer (University of Chicago), issue no. 2, June 12, 2011. Introductory paragraph:

Terrence Malick’s fourth feature, The New World (2004), is a costume drama about Pocahontas, Captain John Smith and the Jamestown colony. On its release it divided reviewers and earned mediocre receipts; some of Malick’s former admirers have been downright dismissive. Although one goal of this paper is simply to make a case for The New World, its concerns are larger than the single film. For Malick has, in recent years, emerged as a key point of reference for a burgeoning, post-Theory philosophical criticism; he is, for example, one of only three directors to receive a monographic chapter in The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film (2009). Disagreement about one of his films, therefore, provides an opportunity to clarify the commitments and aversions of a dynamic field of inquiry. That his fifth film, The Tree of Life, has won the Palme d’Or at Cannes while provoking sharply divided reactions amongst critics only adds urgency to the question.

- If this is not enough (it isn’t) make sure to browse through the “Stuff About Terrence Malick” page currated by Coudal Partners.

The time that Malick takes, and the time that he makes, that he hollows and stretches out on the screen, give us a sense of expansiveness: an epic and lyric feeling. But what is expanded, exactly? Never the moment that something happens, only the before and after … And in this, he finds an unlikely artistic uncle in Jean-Luc Godard (although it is not so unlikely when one realises how much of Pierrot le fou there is in Badlands): in Le Mépris (1963) we can never grasp the moment when a wife stops loving her husband, and Éloge de l’amour (2001) offers (in an inverted chronology) the before and after of a suicide. The philosopher Giorgio Agamben has a powerful way of describing this state of affairs: human beings, he argues, are always caught in a shuffle between feeling as if they are living just before the feast or just after the feast, but never at or in the feast; to live is to be perpetually out of phase with ‘the moment’ when everything (feeling, perception and action; self, other and environment) should click together. (1) To live in the moment, to live your destiny: these are common American delusions, but they are not the sort of Americana to which Malick is drawn.

Wittgenstein asks a question, which sounds like the first line of a joke: ‘How does one philosopher address another?’ To which the unfunny and perplexing riposte is: ‘Take your time’. Terrence Malick is evidently someone who takes his time. Since his first movie, Badlands, was premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1973, he has directed just two more: Days of Heaven, in 1979, and then nearly a 20 year gap until the long-awaited 1998 movie, The Thin Red Line, which is the topic of this essay.

In 1998, almost 20 years after the appearance of his last film Days of Heaven, Terrence Malick’s new work The Thin Red Line was released. It continued his ongoing philosophical project; indeed, it is a film that aspires to the status of a philosophical treatise, manifesting key themes and issues specifically from the work of Martin Heidegger.

Malick’s understanding of cinema seems to be influenced by Heidegger’s contention that it is a cardinal symptom of modernity (which he claims has its deepest roots in Greek thinking) to apprehend reality as something to be differentiated from how it appears to a subjective consciousness, and that the reality is understood at the most fundamental level as something to be mastered. Surely, one of the guiding preoccupations of cinema, if one is to understand it as one of the chief products of modernity, is defining what a cinematic image ultimately is; is it a component of a narrative? A representation of the reality? Objective reality or subjective (psychological) reality? Psychological reality of the filmmaker or the characters? Is it a reflection of ideological values?

The very notion of a man who translated Martin Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons into English being allowed to film mega-budget Hollywood movies starring George Clooney, John Travolta, and Colin Farrell is enough to make some of us believe there’s justice of some rough kind in the world.

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Movies

- Tagged: Cannes, Heidegger, Malick, The Tree of Life, time, world