An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Columbus Museum of Art: “Morning Sun” by Edward Hopper, oil on canvas, 28 1/8 x 40 1/8″, 1952. Large format retrieved from NPR.

NPR has an interesting piece about the “pensive lady in pink”:

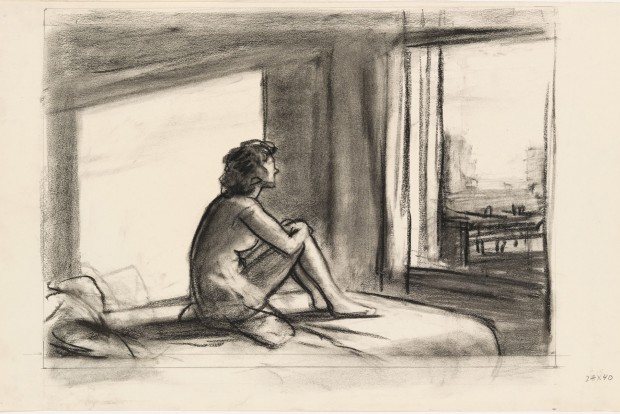

It’s one of the ultimate images of summer: a woman in a short, pink slip sits on a bed, her knees pulled up to her chest, gazing out a window. Her hair is tucked back into a bun. Her bare arms rest lightly on her bare legs. (“Hopper’s Pensive Lady In Pink Travels The World” by Susan Stamberg, August 20, 2012)

In the book Realism by Kerstin Stremmel, which is part of the Taschen’s Basic Art movement and genre series, the author draws attention to two features in the painting:

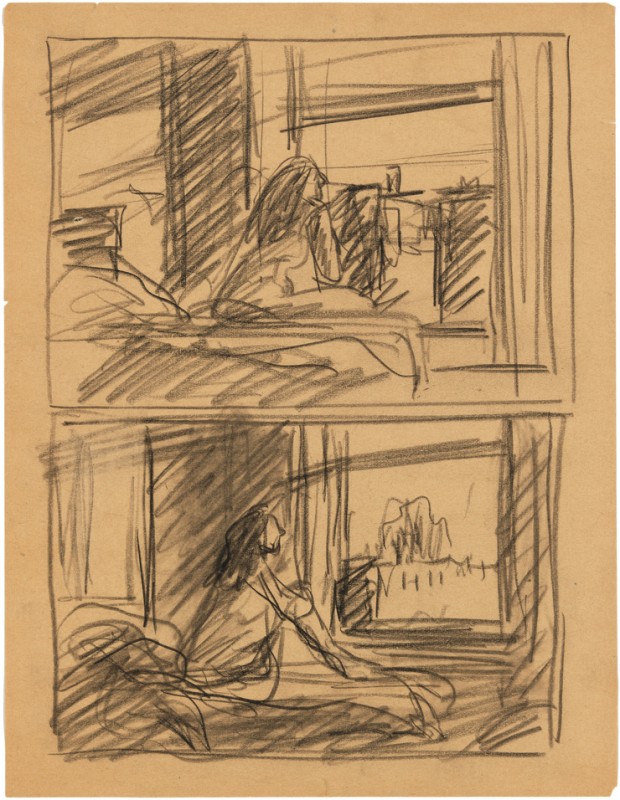

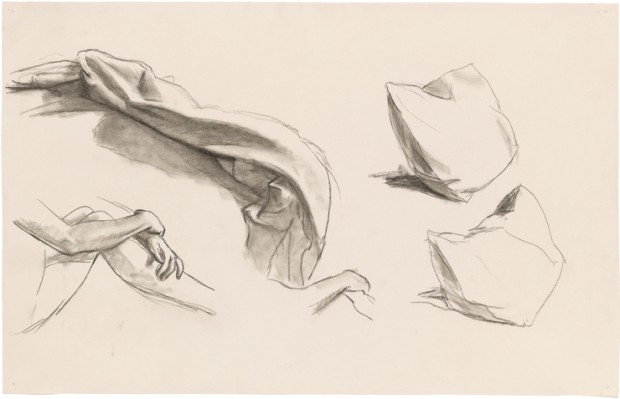

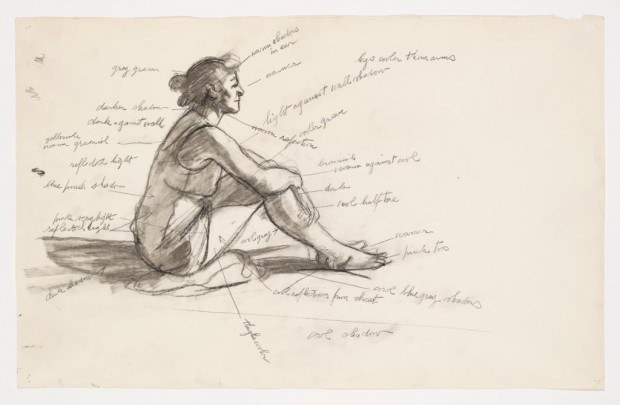

Two constants in Hopper’s pictorial output are visible in this picture. One is the relationship between interior and exterior – separate, yet linked by the motif of the window, through which, however, the woman’s gaze does not penetrate to the outside, as she seems to be imprisoned within herself. The other focus is the importance of the light and its effect, which turn up time and again in Hopper’s picture: “Perhaps I am not very human. My concern was to paint sunlight on the wall of a house.” In a preliminary study for this painting, it is possible to see that his interest focused on the way the light fell on the woman’s body. In the painting, a sunny rectangle can be seen on one wall of the room, but although the room is bathed in light, it seems cold, and the pale skin of the woman, whose face comes across as an expressionless mask, shows reddening on her hands and toes, and a slight shiver seems to jump across from her to the beholder. (Taschen, 2004: 58)

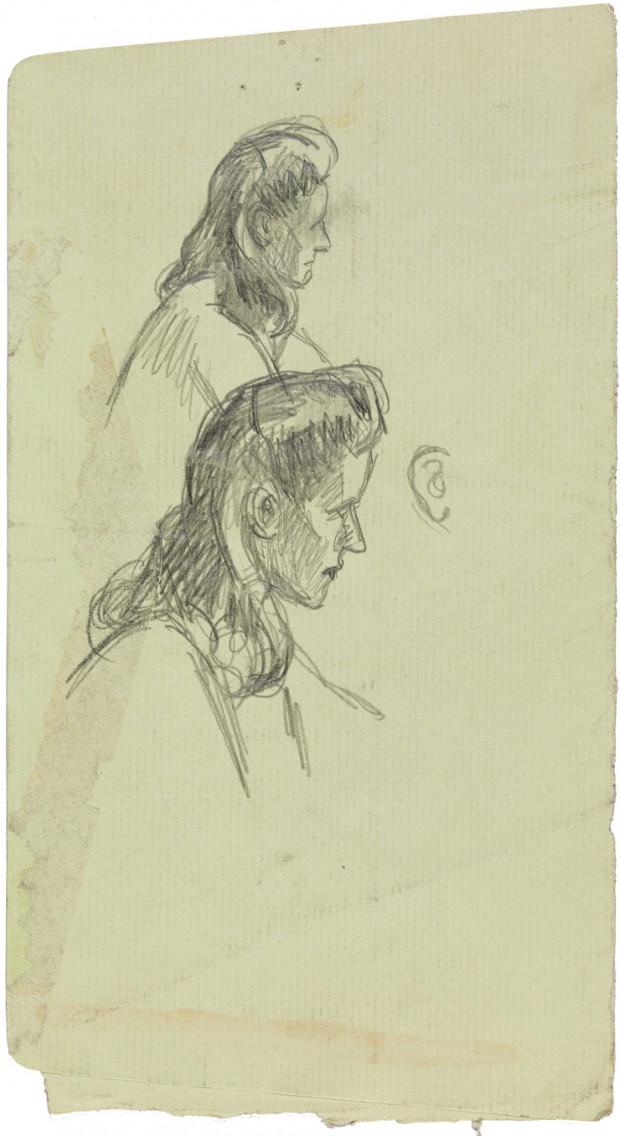

The model for the painting was Hopper’s wife Josephine, with whom he had a difficult relationship. Herself a painter, she was to become Hopper’s only female model after their marriage in the mid-20s. At the time those drawings were made, she was 69 years old. Some of the studies show her features in greater details, as one can recognize an older woman. But the final painting depicts what looks like a somehow younger, generic female figure.

In Edward Hopper Light and Dark, the author suggests that “[t]he woman is less important than the light that strikes her” (Gerry Souter, Parkstone International, 2012: 234). Although I understand the value of this remark, I can’t find myself to agree with it. I feel nobody would even look at the room –let alone the light– if the female figure wasn’t present. Furthermore, the light itself is provided with a unique quality by the fact that it is met by this ineffable gaze. Some have suggested that the woman is “seemingly transfixed […] by profound metaphysical thought” (“The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster” by James Peacock, Janus Head, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 82).

I rather think she’s absentminded, lost among the foggy preoccupations that populate the realm between slumber and wakefulness.

• • •

Previously:

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Painting

- Tagged: bed, Edward Hopper, light, morning, solitude, sun, woman