An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

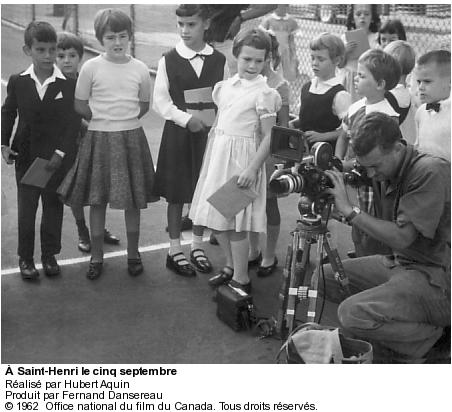

☛ September Five at Saint-Henri by the National Film Board of Canada, 1962, English version: 27″10′, French version (À Saint-Henri le cinq septembre): 41″41′. The above photo is a still from the English version taken at 8″46′.

From the NFB website:

This short film is a series of vignettes of life in Saint-Henri, a Montreal working-class district, on the first day of school. From dawn to midnight, we take in the neighbourhood’s pulse: a mother fussing over children, a father’s enforced idleness, teenage boys clowning, young lovers dallying – the unposed quality of daily life.

The film can be watched entirely online on the NFB/ONF website: French version, English version. Flash is required.

• Differences between French and English versions

I wrote to the NFB about the duration difference between the French and the English version (almost 15 minutes). I was told the English version was specifically produced for the CBC network and most likely needed to be shorten in order to accommodate television schedule.

The images are accompanied by a voice-over narration. It’s important to note that the French and English version do not have the same narration. The commentary for the French one was written and read by Jacques Godbout. Whereas Bill Davies wrote the text for the English version. I couldn’t find the name of the French Canadian who read the English commentary (with a strong French Canadian accent).

• They worked on September Five at Saint-Henri

Aside from writing and narrating the French commentary, Jacques Godbout also did the editing, along with Monique Fortier. In an interview he did in 1974, he explained how he came to work on the film:

L.B. – Qu’est-ce qui vous a amené ensuite à faire À Saint-Henri, le 5 septembre?

J.G. — Ce film est le fruit d’une recherche de Monique Bosco et de Hubert Aquin. Fernand Dansereau avait eu cette idée: si tous les cinéastes de l’équipe française de l’O.N.F. envahissent un quartier comme Saint-Henri, nous pourrons rendre témoignage de ce quartier. Alors nous avons quadrillé le quartier. Cela a donné 40 à 50,000 pieds de pellicule sans queue ni tête puisque chaque cinéaste partait tourner de son côté. Claude Jutra a essayé de faire un montage et, après plusieurs mois, a déclaré qu’il n’y avait rien à faire avec cela. À ce moment-là, on m’a proposé de faire un film sur les pompiers. Cela ne m’emballait pas. Or, j’ai proposé de faire un échange : passez Les Pompiers à quelqu’un d’autre et je vais faire le montage de À Saint-Henri, le 5 septembre. (Séquences: “Entretien avec Jacques Godbout”, no. 78, p. 6 (Permalink, PDF)

The film was directed by Hubert Aquin, one of the most famous writer from the Province of Quebec. He’s most notably known for his novels Prochain épisode (1965, translated as Next Episode) and Trou de mémoire (1968, translated as Blackout). Aquin was employed by the NFB from 1960 to 1963. During this period he worked on seven different films. See Canadian Journal of Film Studies: “The Missing Mythology: Barthes in Quebec” by Scott McKenzie, vol. 6, no. 2, Fall 1997, p. 66 (PDF).

The magnificent song which opens and closes the film was written and performed by Raymond Lévesque, also a singer and songwriter from the Province of Quebec, notably known for his song “Quand les hommes vivront d’amour” (listen to it on YouTube).

• A fine example of “direct cinema”

The film was later recognized as one of the most interesting example of “direct cinema” (cinéma vérité) produced by the NFB. There’s a lot of resource online about the history of “direct cinema”. Here are three sources pertaining specifically to September Five at Saint-Henri:

- From the Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America: “Direct Cinema and the National Film Board” by Martin Delisle:

Thus, after Les Raquetteurs came a string of films created for television that featured various aspects of life in Quebec; these films began to offer a close-up portrayal of the province’s inhabitants, which had never been shown on screen before. Among these films some of the most notable are: La Lutte (Claude Jutra, Claude Fournier, Marcel Carrière, Michel Brault, 1961), Golden Gloves (Gilles Groulx, 1961), À Saint-Henri le 5 Septembre (Hubert Aquin, 1962) and Bûcherons de la Manouane (Arthur Lamothe, 1962). They were a far cry from the sweetened and sanitised version of life in Canada portrayed in previous films presented by the National Film Board.

- In the national interest: a chronicle of the National Film Board of Canada from 1949 to 1989 by Gary Evans, University of Toronto Press, 1991, p. 84:

À Saint-Henri le 5 septembre ($21,564) was probably the most profound expression of cinéma direct and identified itself as an homage to French filmmaker Jean Rouch.

- NFB kids: portrayals of children by the National Film Board of Canada 1939-89 by Brian John Low, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002, pp. 105-107:

September 5 at Saint-Henri employed twenty-height filmmakers using “New Wave” technique to depict “Smokey Valley”, an industrial district of Montreal. The Genius of the film lies in its masterful mirroring of the moods and relations of an entire working class community so that the seam between “what is” and “what ought to be” virtually disappears.

• A controversial film

It’s interesting to learn that September Five at Saint-Henri was a controversial film when it came out. Some of the people from Saint-Henri who appear in the film were not happy with the way they were represented. Another problem lies in Godbout’s commentary which was perceived by some as being condescending (an intellectual film about a working class community).

- From “The History of Public Access Television” by William D.S. Olson, 2000:

The first Challenge for Change documentary, “September 5 at Saint-Henri,” went into distribution amidst “extremely negative” reactions on the part of its subjects, who suffered ridicule from their neighbors. One family was so affected that they considered pulling their children from the local school.

Olson takes this information from Gilbert Gillespie’s book Public access cable television in the United States and Canada, Praegner, 1975, p. 21.

- On his website, author and movie critic Yves Lever put together an exhaustive file about the film reception (in French). See for example this comment by Jacques Godbout published in the periodical Parti Pris (no 7, avril 1964, p. 9.):

En fait très peu de ces films de la série “Temps présent” surent satisfaire la direction d’une part, ceux à propos desquels le film était fait, d’autre part. L’exemple le plus simple reste celui de À Saint-Henri le 5 [sic ] septembre où ce court métrage servit dans la campagne électorale comme preuve du mépris des intellectuels pour le petit peuple… le petit peuple n’était pas de cet avis mais les notables, (curé, journal du quartier, etc.) n’admettaient pas qu’un documentaire montre aux habitants du quartier à quoi >ressemblait ce quartier. Le danger que représente le documentaire, en effet, est vite aperçu par ceux qui ont tout à cacher: et rares sont les endroits où les équipes (françaises) de l’ONF ne se font que des amis.

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication, Movies

- Tagged: daily life, direct cinema, documentary, intellectual, NFB, ONF, Quebec, working class