An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

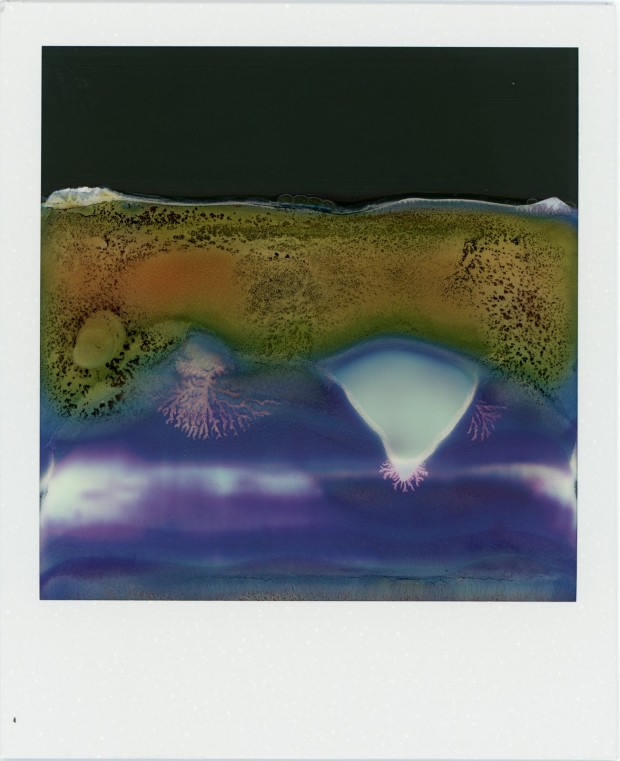

☛ William Miller: “Ruined Polaroid #7” from the Ruined Polaroids series, Polaroid picture taken with a SX-70 camera, subsequently enlarged at 76.2 x 91.4cm, 2010-2011. © 2012 William Miller.

William Miller was born in New York in 1969. He’s a photojournalist whose work has appeared in such publications as Harpers, Paris Match, GQ, the New York Post and many more. He studied photography at Bard College with Larry Fink and Stephen Shore (where both are still teaching as of spring 2012). He currently lives in Brooklyn and works in various places all around the world. In 2011 he won a Celeste Prize award for one of his “Ruined Polaroids” photo.

In 2010, Miller bought a used SX-70 Polaroid camera at a yard sale. The SX-70 was a popular model in the early 70’s having sold 415,000 units by 1973. It was also a model of choice for some prominent photographers and artists such as Ansel Adams, Walker Evans and Andy Warhol1.

However, the camera Miller had bought was no ordinary camera: it was broken. In a email exchange I had with him, Miller generously shared the details of how the Ruined Polaroid series came to light (pun intended):

All but the first few of the Ruined Polaroids were taken in 2011 although one could say that I’ve been producing them my whole life. Anyone who has ever worked with Polaroid has. I figure about 5% of all polaroids fail for one reason or another. We all tend to throw them out. They’re a statistical anomaly of such a complicated technology. My slightly broken SX-70 camera inverted the statistics. I was getting ruined pictures almost all the time. I bought the camera in 2010 and tested it. It didn’t work properly. About 6 months later I tried it again and it didn’t work properly. At this point I had 5 messed up looking polaroids. The project was forced on me by this failure of a process.

What appears on the photographs produced by the broken camera could be called from an experimental science point of view “artifacts”: they constitute unintended results in a process which aimed at something completely different2. In the case of Ruined Polaroids the normal function of the SX-70 camera is to produced an accurate photographic representation of the world (in color). However, what Miller’s broken camera has to offer is an unmeditated presentation of its own mechanical and chemical process. The medium doesn’t passively (or transparently) offer itself as a window on something else. On the contrary, it stands as an accident in the way of the usual process of representation, as if it was actually blocking the view, imposing instead its own awkward (and strangely seductive) presence.

Over at the online magazine Lens Culture, Miller explains:

This project, Ruined Polaroids, is an unintended exploration into the three-dimensional physical character of an antiquated photographic medium that touches on subjects from the artistic value of chance, to questions of what constitutes a photograph. I say unintended because what I’m focusing on here is a technological anomaly. The failure of a process.

At first I didn’t see anything else aside from the anomaly in Miller’s ruined Polaroids. I was quite surprise when I first spotted vague and fuzzy traces of what the camera was actually aiming at when the photos were produced. Some of them do indeed show glimpse of a world, as if seen through a psychedelic haze. #35 shows what looks like the silhouette of a building or a tree. In the center of #31 one can guess the word “EGYPT” printed on what must be a map (in the lower right corner also appears the words “RED SEA”). #18 barely displays the tail of an alligator or a crocodile on a tiled pavement as viewed from a high angle, downward perspective. #45 may have recorded part of a graffiti (somewhere in SoHo if the file’s name is accurate).

Today, there are strong nostalgic feelings associated not only with the look and feel of Polaroid photos (hence the Poladroid app), but with old recording media in general (the massive popular success of Instagram’s filtered photos is a good testimony of the phenomenon: I wrote about this longing for an phantasmic past regarding the paintings of David Lyle). A little bit of intended artifacts is sometime welcomed. It can even make things appear to be more “realistic”: that’s why we introduce grain and flares in computer-generated imagery (CGI). Sometime those artifacts become too obvious. It’s usually seen as a mistake (director JJ Abrams is well known for the perceived overuse of simulated lens flares in his films).

In Miller’s case however, the overwhelming presence of artifacts is precisely what is sought-after. All the details ―the words on a map, the crocodile’s tail, the graffiti― are lost to the mechanical and chemical distortions of the Polaroid. What is gained in exchange, as Miller explains, is the possibility to think about photography itself: the mediation process by which we normally get visual access to (a) reality. How much of it is determined by our own intention and how much of it by the means we’re using in the process? At what point do we become consciously aware of the artifacts of a given medium?

I suspect however that thinking comes second in what a viewer is more likely to do when experiencing Miller’s ruined Polaroids. Letting one’s gaze wander erratically in their chaotic field of colors is a temptation one is unlikely to resist at first. I know I didn’t.

• • •

First spotted via Motherboard.

Related information available online:

- The Ruined Polaroid series has its own website. Clicking on a given photo will darken the background and center it. The photo size will be adjusted according to the size of the user’s browser window (the plugin I’m using here does the very same thing). If you’re not visiting the site from a computer equipped with a big screen, I suggest right-clicking on the picture and asking for it to be open in another tab: it will display the picture at its highest resolution and it’s really worth it (you can do the same thing here or simply click on any image and then on the “download” link appearing in the lower left corner of the display window).

- William Miller’s main website allows one to browse through his portofolios or check his short biography. It also has a link to his photography blog (which is regularly updated).

- As a comparison, see also the work of artist Eric Rondepierre who primarily works with physical film frame (either 16 mm or 35 mm). See especially Moires and Les Trente Étreintes.

- Related to the last suggestion, a short essay on the art of experimental filmmaker Bill Morrison (in French): “Notes sur l’imaginaire de la ruine au cinéma” by André Habib, Hors Champ, June 14, 2004.

- On a similar note see “MADMEN Bittorrent Edition” on Vimeo:

Video comprising one episode of Madmen incompletely downloaded from the internet via bittorrent. The video has been linearly edited, no digital effects were used and all jump cuts and repeats are in the corrupted file. The video captures an episode of the popular TV show in the act of being shared by thousands of users on bittorent. The video simultaneously acts as a visualisation of bittorrent traffic and the practice of filesharing and is an aesthetically beautiful by product of the bittorrent process as the pieces of the original file are rearranged and reconfigured into a new transitory in-between state.

The experience wouldn’t be complete without a thorough technical explanation of encoding/decoding process proper the digital video files most commonly exchange over P2P network (via Waxy Links).

• • •

1. The definitive article on the subject is probably “Polaroid’s SX-70: The Art and Science of the Nearly Impossible” by Harry McCracken, Technologizer.com, June 8, 2011.↩︎︎

2. For more see the article “Artifact” at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.↩︎︎

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Photography, Technology

- Tagged: abstraction, accident, analogous, artifact, failure, medium, Polaroid, ruins, William Miller