An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

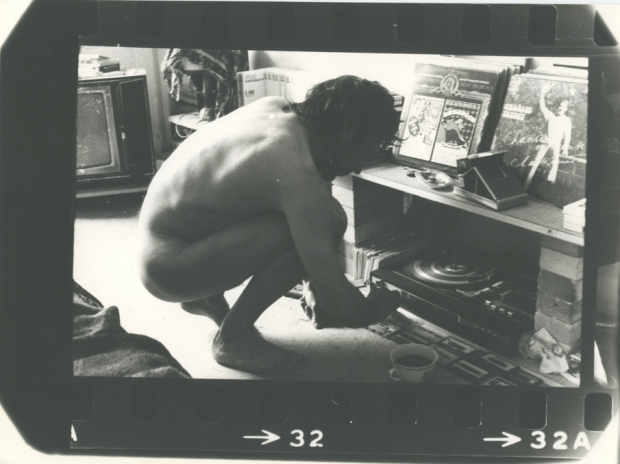

☛ Répertoire de la Photolittérature Ancienne et Contemporaine: Portrait de Jean Eustache by Alix Cléo Roubaud, 1981. © Alix Cléo Roubaud.

This is a portrait on French cinematographer Jean Eustache (1938-1981), but it also looks like a still from his most notorious film The Mother and the Whore (1973): there’s a scene in the Parisian apartment of Marie (Bernadette Lafont) where the main character Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) get out of bed ―although not totally naked but covered with a bed sheet― in order to put a record on the turntable.

The photograph was recently used over at MUBI to illustrate the English translation ―by Ted Fendt― of an interview with Jean Eustache originally published in 1971 (“Jean Eustache, entretien avec Philippe Haudiquet”, La Revue du Cinéma, no. 250, May 1971; for more information about the now defunct publication La Revue du Cinéma see SubStance, vol. 3, no. 9, Spring 1974, pp. 147-151, PDF). It’s worth noting this interview was made two years before the release of Eustache acclaimed “film-river” (according to an expression by French critic Serge Daney) La Maman et la Putain (The Mother and the Whore).

The photographer who took the intimate portrait is Alix Cléo Roubaud, a close friend of Jean Eustache. Although she was not well known during her lifetime (she died in 1983 at the very young age of 31 years old from a pulmonary embolism) she’s been gaining some posthumous recognition in recent years. Among other things, this recognition is made possible by the edition of her personal journal. Edited and introduced by her husband the poet Jacques Roubaud, Alix’s Journal (1979-1983) was first published in 1984 and re-edtied in 2009 (Seuil).

In 2010, an English translation was published as well. Here’s how her husband introduces her and explains how she came to work with the photographic medium:

Born in Mexico (her father, Arthur Blanchette, a diplomat; her mother, Marcelle Blanchette, a painter), Alix was Canadian and bilingual. Alix’s Journal is written in French (mostly) and English. Nomadic during her childhood and adolescence (living in South Africa, Egypt, Portugal, and Greece), she had retained the sense from these wanderings of not spontaneously possessing either of her two languages (French, her maternal language, and English, her paternal language), which she spoke and wrote interchangeably, having in each an invisible accent stemming from no particular region. She gave the impression of being, in each, “always translating.”

She completed her secondary schooling in French lycées: she derived her love for the sun from Athens; in those years, she had hardly suffered from her asthma, and she associated the joy of sunlight with that of breathing effortlessly, freely. She studied architecture and psychology in Ottawa, and philosophy in Aix-en-Provence and in Paris.

For her, the language of philosophy was German, ever since she discovered Wittgenstein and then Benjamin: both, for different reasons, themselves “wanderers,” having lived for a long time in that state of quasi-solipsistic linguistic singularity that so fascinated her―Benjamin in Paris and Wittgenstein in Cambridge. There is no doubt a similar motivation behind her attraction to the work of Gertrude Stein.[…]

That same moment in August 1978 also marked Alix’s discovery of photography. It happened in the infinitely serene solitude (this is how she experienced her stay) of a small spa town in the mountains (but medium-sized mountains, not near the Alps or the Pyrenese) popular with spa-goers of limited means in the center of France―incredibly atypical for her, who was touching and at the same time absurd with all her old-fashioned manners and obsessions.

More precisely, it was that moment, in those days of complete but peaceful isolation, that she discovered it was photography, which until then had been but one of many possible paths she envisaged for herself, and which she had only practiced intermittently (she was to keep almost none of the photographs she had taken before then), which would become, along with her Journal, her sole and essential activity, and the only one that would be turned outward, that would be able to brave the eyes of others.[…]

In conclusion, let me return to the very particular conception Alix had of her work as an artist. She did all her own printing, and recognized as part of her oeuvre only those images that she herself had consigned to paper.

She told me one day that a photographic negative was no more important than a pallet is to a painter. Any photographic work that she signed was composed by her hand with the aid of light and chemistry. Transposing, for her own use, and without claiming any philosophical significance to this borrowing, a Wittgensteinian distinction, she opposed the living image to what she called a piction: a mere “idle” image. On a negative, she used to say, ther is only a piction. “Printing” alone can set it into motion and truly make an image. (Alix’s Journal, tr. by Jan Steyn, Dalkey Archive Press, 2010, pp. 8-9, 13-16; originally published in French as Journal (1979-1983), Paris: Seuil, 1984)

In 1979, Jean Eustache made a short film about Alix Cléo Roubaud, which was released a year later in 1980. Nick Pinkerton describes the film, simply titled Les Photos d’Alix, in a essay he wrote in 2008 about “The life and films of Jean Eustache”:

Les Photos d’Alix, made the same year, centers on a troubling obfuscation of meaning, the unreliability of images. Alix-Clio [sic] Roubaud sits down with a teenager, played by Eustache’s son, Boris, to explain the significance of the photographs she has taken. As the explanations proceed, it’s gradually apparent that they no longer relate to the photograph shown on screen, that the explanations seem to have been completely reshuffled (the great accomplishment is that it’s difficult to say just how or when this sleight-of-film is pulled off). (Moving Image Source, “His Little Loves. The life and films of Jean Eustache.” by Nick Pinkerton, June 12, 2008)

Here’s a photo from the making of Les Photos d’Alix: from left to right are Jean Eustache, Alix Cléo Roubidaud and Jean Eustache’s son, Boris. This photo was retrieved from the PHLiT website.

Below are two more photos of Jean Eustache taken by Alix Cléo Roubaud (undated). Both photos were retrieved from Alix’s official Facebook page. More relevant links are provided after those images.

-

The website for the Répertoire de la Photolittérature Ancienne et Contemporaine has one of the richest textual and iconographic online archive pertaining to Alix Cléo Roubaud. It offers references to numerous texts by or about the young photographer, as well as 16 photos adequately identified. A great place to start a serious research.

-

The Silo offers a review in English of Jean Eustache’s film Les Photos d’Alix: “Alix Cléo Roubaud” by Raphael Rubinstein, October 5, 2011.

-

Le Portail de la Photographie has 23 photos by Alix Cleo Roubaud. There are all properly identified and presented in a medium size.

-

L’intermède has a very good review of the Alix’s Journal (in French) which also offers a short analysis of Eustache’s film Les Photos d’Alix:

Dans son dernier film, le réalisateur Jean Eustache (1938-1981) met en scène son amie Alix expliquant à son fils, Boris Eustache, certaines de ses photographies. Les Photos d’Alix (1980), court-métrage de 18 minutes, qui devrait être disponible dans le courant de l’automne 2010 dans l’intégrale du réalisateur, permet à la photographe d’exposer son travail et de le commenter, affirmant par là certaines de ses théories esthétiques. Cependant, le commentaire est court-circuité par le montage d’Eustache qui travaille à décaler le discours d’Alix de l’image dont elle parle réellement. Travail subtil qui dit sans doute beaucoup du rapport du cinéaste à l’image, complexe, mais drôle tout autant : ainsi, le décalage fait qu’Alix parle d’un coucher de soleil sur Fès alors que la photographie montrée la représente nue dans un cliché intitulé “pornographie bourgeoise”. Certaines des phrases qu’elle prononce dans le film sont reprises dans les deux textes inédits placés en Annexes dans le Journal. (“Alix Cléo Roubaud, le quai des brumes” by Alexandre Salcède, March 5, 2010)

-

Essay in French: “L’acte dans Les Photos d’Alix de Jean Eustache” by Carole Wrona, in L’image récalcitrante, ed. by Murielle Gagnebin and Christine Savinel, Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2001, pp. 231-243.

-

Essay in French: “Eustache, Alix et ses Photos: «un futur antérieur sans cesse déchiré»” by Paul Léon, in Traces photographiques, traces autobiographiques, ed. by Danièle Méaux, Jean-Bernard Vray and Philippe Antoine, Université de Saint-Etienne, 2004, pp. 137-144

-

Texte et Image dans la construction biographique d’Alix Cléo Roubaud, Master’s thesis by Pauline Donnio, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2011. PDF.

-

Stardust Memories.com: “Les photos d’Alix” by Florence Maillard.

-

As critic Nick Pinkerton remarks in his essay, the films of Jean Eustache are not easily accessible:

Part of what is so attractive about Eustache is, let’s be frank, his “undiscovered” status: his films are nonexistent on DVD, and rarely screened—such preemptive barriers to trend-sniffers are no small thing in the era of downloadable cool.

For those who are willing to discover The Mother and the Whore in such viewing conditions, it’s possible to watch all of its 220 minutes on YouTube, with English subtitles (part 1, part 2).

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Movies, Photography

- Tagged: Alix Cléo Roubaud, Benjamin, France, image, Jean Eustache, photographer, portrait, representation, Wittgenstein