An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

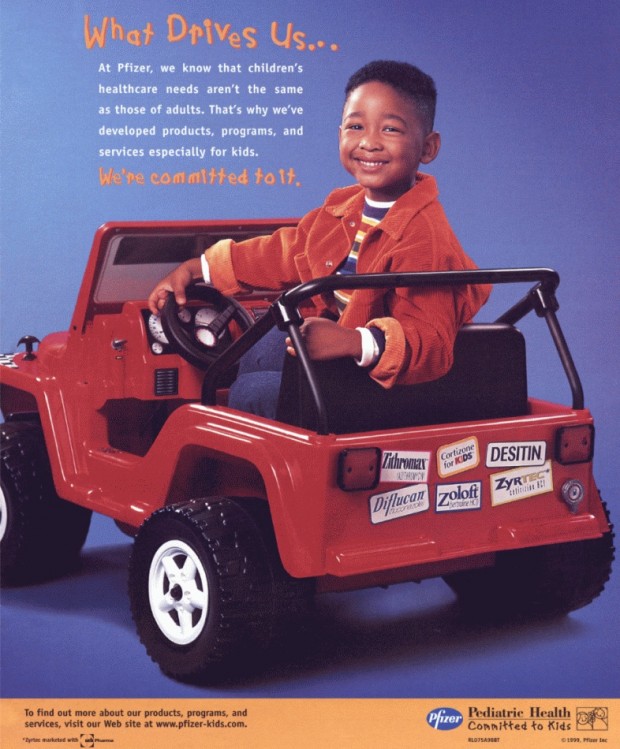

☛ Bonkers Institute: “What Drives Us” Pfizer Advertisement, 1999. NOTE: “Zoloft Kid” which I use in the title of this post is not the official Pfizer title for this add: it’s the title use by Ben Hansen on his website.

Recently, Marcia Angell from The New York Review of Books shed some light on the relationship between kids and antipsychotic drugs:

What should be of greatest concern for Americans is the astonishing rise in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness in children, sometimes as young as two years old. These children are often treated with drugs that were never approved by the FDA for use in this age group and have serious side effects. The apparent prevalence of “juvenile bipolar disorder” jumped forty-fold between 1993 and 2004, and that of “autism” increased from one in five hundred children to one in ninety over the same decade. Ten percent of ten-year-old boys now take daily stimulants for ADHD—”attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder”—and 500,000 children take antipsychotic drugs. (The New York Review of Books: “The Illusions of Psychiatry” by Marcia Angell, July 14, 2011; more below)

From time to time, I come across those disturbing pharmaceutical drug ads while surfing the Internet. One has to keep in mind that they are rarely intended for the general public: they usually appear in medical journals and are specifically intended to practitioners (under the 1971 United Nation Convention on Psychotropic Substance, manufacturers must “prohibit the advertisement of such substances to the general public”; although not all manufacturers respect the convention, see here for more info). I thought I’d take the time to gather some relevant links.

From others similar ads, I learn that Thorazine (which really is chlorpromazine, a typical antipsychotic drug) is good for treatment against alcoholism, anxiety, asthma, arthritis, severe pain such as burns, cancer, cancer phobia, child behavior disorders, hyperkinetic children, intractable hiccups, hostility, mania, menopause, peptic ulcers, senility, vomiting, disturbed and non-disturbed patients, and much more.

The Bonkers Institute where I found the advertisement depicted above has a large collection of such ads, along with detailed source attribution (which is exceptional: usually, those ads are reblogged without any indication about their origin: see below).

The Bonkers Institute is a website founded in 2005 (if I’m not mistaken) by mental health advocate Ben Hansen, a.k.a. Dr. Bonkers (his pseudonym) to debunk and expose dubious practices by the various actors of the pharmaceutical industry. See for example this article by the New York Times, “In Some States, Maker Oversees Use of Its Drug” (by Stephanie Saul, March 23, 2007), based on documents obtain by Hansen.

For more information about The Bonkers Institute and Ben Hansen, see its About page and read this 2009 interview: “An Interview with Dr. M.I. Bonkers (aka Ben Hansen) About Atypical Antipsychotics” (by Michael F. Shaughnessy, February 12, 2009).

For more images of pharmaceutical drug ads, consider the following links:

- On Flickr, Whispering Ibis’ photostream has two sets of “vintage pharmaceutical ads” (53 photos) and “vintage medical ads” (207 photos). The ads are provided without source attribution. To my knowledge, it’s nonetheless one of the richest collection available online. The owner of this Flickr account also uploaded a selection of those images on her LiveJournal account.

- Again on Flickr, Carmen Alonso Suarez’s photostream has a set of 174 ads from the 50s’, 60s’ and 70s’ published in the Spanish journals Clínica Rural and Glosa (that’s the only information provided for the source of the images).

- The Japanese Gallery of Psychiatric Art has 70 scans of original pharmaceutical ads from Japanese journals. For each and every one of them, the year of publication and the name of the journal where it originally appeared is provided.

• • •

As a complement to this material, one might consider a two-part review by Dr. Marcia Angell published this summer in The New York Review of Books: “The Epidemic of Mental Illness: Why?” (June 23, 2011) and “The Illusions of Psychiatry” (July 14, 2011). This two-part review was followed by an exchange with readers: “The Illusions of Psychiatry’: An Exchange”. (August 18, 2011).

Marcia Angell is a known critic of the pharmaceutical industry. In her review, she concentrates on three recent books: The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth by Irving Kirsch (Basic Books, 2009), Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America by Robert Whitaker (Crown, 2010) and Unhinged: The Trouble With Psychiatry—A Doctor’s Revelations About a Profession in Crisis by Daniel Carlat (Free Press, 2010).

Below are some excerpts taken from Marcia Angell’s two parts article. They are taken out of a rich and well documented context: I would strongly advise anyone interested in what they read here to go read Angell’s article and the exchange that followed. From the first part:

A large survey of randomly selected adults, sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and conducted between 2001 and 2003, found that an astonishing 46 percent met criteria established by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for having had at least one mental illness within four broad categories at some time in their lives. […]

Nowadays treatment by medical doctors nearly always means psychoactive drugs, that is, drugs that affect the mental state. In fact, most psychiatrists treat only with drugs, and refer patients to psychologists or social workers if they believe psychotherapy is also warranted. The shift from “talk therapy” to drugs as the dominant mode of treatment coincides with the emergence over the past four decades of the theory that mental illness is caused primarily by chemical imbalances in the brain that can be corrected by specific drugs. […]

First, [all three authors] agree on the disturbing extent to which the companies that sell psychoactive drugs—through various forms of marketing, both legal and illegal, and what many people would describe as bribery—have come to determine what constitutes a mental illness and how the disorders should be diagnosed and treated. […]

Second, none of the three authors subscribes to the popular theory that mental illness is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. […]

For example, because Thorazine was found to lower dopamine levels in the brain, it was postulated that psychoses like schizophrenia are caused by too much dopamine. […] Thus, instead of developing a drug to treat an abnormality, an abnormality was postulated to fit a drug. […] [By the same logic] one could argue that fevers are caused by too little aspirin. […]

From the second and last part:

These efforts to enhance the status of psychiatry were undertaken deliberately. The APA was then working on the third edition of the DSM, which provides diagnostic criteria for all mental disorders. The president of the APA had appointed Robert Spitzer, a much- admired professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, to head the task force overseeing the project. The first two editions, published in 1952 and 1968, reflected the Freudian view of mental illness and were little known outside the profession. Spitzer set out to make the DSM-III something quite different. He promised that it would be “a defense of the medical model as applied to psychiatric problems,” and the president of the APA in 1977, Jack Weinberg, said it would “clarify to anyone who may be in doubt that we regard psychiatry as a specialty of medicine.” […]

Not only did the DSM become the bible of psychiatry, but like the real Bible, it depended a lot on something akin to revelation. There are no citations of scientific studies to support its decisions. That is an astonishing omission, because in all medical publications, whether journal articles or textbooks, statements of fact are supposed to be supported by citations of published scientific studies. (There are four separate “sourcebooks” for the current edition of the DSM that present the rationale for some decisions, along with references, but that is not the same thing as specific references.) […]

Of the 170 contributors to the current version of the DSM (the DSM-IV-TR), almost all of whom would be described as KOLs, ninety-five had financial ties to drug companies, including all of the contributors to the sections on mood disorders and schizophrenia. […]

Unlike the conditions treated in most other branches of medicine, there are no objective signs or tests for mental illness—no lab data or MRI findings—and the boundaries between normal and abnormal are often unclear. […]

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Technology

- Tagged: advertising, behavior, brain, drugs, mental illness, pharmaceutical company, psychiatry, psychoactive drugs, psychotropic substance