An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

☛ Boston.com / The Big Picture: “A banner reads ‘yes to the society no to the power’ during a rally against plans for new austerity measures, in Thessaloniki, Greece, June 15, 2011. A 24-hour strike by Greece’s largest labor unions was to cripple public services, as the Socialist government began a legislative battle to push through last-ditch cost cutting reforms that would exceed its own term in office. Demonstrators have camped outside parliament since May 25, 2011. (Nikolas Giakoumidis/Associated Press)”

This photo is part of a photoset put together for Boston.com’s photo blog The Big Picture to illustrate the undergoing economic crisis in Greece. Here’s the introduction to this collection of photos by director of photography Paula Nelson:

Over the last decade, Greece went on a debt binge that came crashing to an end in late 2009, provoking an economic crisis. Over the next two years, Greece relied on bailout money from its richer neighbors and implemented austerity measures meant to cut its bloated deficit and restore investor confidence. But by June 2011 it found itself deep in a second recession, near the end of its cash and facing a political crisis, as anti-austerity demonstrations grew. Violence broke out this week during one of those demonstrations, injuring 11, as the frustration continued to grow and no quick fixes emerged. Today, Greece’s Prime Minister George Papandreou, in a broad cabinet reshuffle, appointed a new Finance Minister, Evangelos Venizelos, in hopes of turning his country around.

On the photograph displayed above, all one can read actually are two words: ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ (“KOINONIA”) on top, and ΕΞΟΥΣΙΑ (“EXOUSIA”) just under it. Following the captions provided by Associated Press, the whole banner may have originally read something like: ΝΑΙ στην ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ / ΟΧΙ στην ΕΞΟΥΣΙΑ.

The first word displayed on that banner, ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ, can be understand as “society” in a very broad and loose sense (as Boston.com choose to translate it). However it refers more precisely to “community”. See Perseus’ Greek Word Study Tool: κοινόν, as well as the way it’s been traditionally used in Christian texts (Wikipedia: Koinonia). For the usual sociological distinction between “society” and “community”, see Ferdinand Tönnies’s book Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (first published in 1887: Google books, Wikipedia).

The second word on the banner, ΕΞΟΥΣΙΑ, usually translates as “power” or “authority” (to do a thing). The Liddell and Scott Greek Lexicon also gives as a second meaning “abuse of authority, licence, arrogance” (Greek Word Study Tool: ἐξουσία)

As for the proposition “yes to the society no to the power” it is perfectly understandable (enough with abusive power) although it also appears to be problematic (at least in its English translation): how is it possible to think a way of living together without any manifestation of power? To put it even more simply: is a relationship without power even imaginable? Maybe the banner should be understand as a called for the renewal of social “communion”? I guess the answer depends on how we understand the concept of “power”.

Consider the arm with a clenched fist outstretching through the “omicron” of the word ΕΧΟΥΣΙΑ. It could be seen paradoxically as an obvious, explicit manifestation of power, even a call for violence. In a recent interview published in The Minnesota Review Roberto Esposito, author of an important book about the concept of community, explained his view about conflict and social order:

On this point here too Foucault—and Nietzsche before him—took a different route that in its development also makes reference to Machiavelli: there cannot be order without conflict. This is the reason, following the lines of the actual, why one needs to take a stand. One needs to choose among different, sometimes juxtaposed possibilities that the present offers. I want to insist on the importance of Machiavelli here: unlike Hobbes’s absolutist or proto-liberal idea that conflict must come to an end so that order can be born, Italian thought holds that order is one with conflict (Gramsci will take this up again in his writings, as will the Italian operaismo of the 1960s and 1970s). “Plane of immanence” in political philosophy means this and nothing else: conflict does not break up order from the outside, but is always already a part of order. One of the theoretical problems that needs to be posed today is that of the apparently contradictory relation between antagonism and immanence: how are we to think an immanent antagonism? (“On Contemporary French and Italian Political Philosophy: An Interview with Roberto Esposito”, The Minnesota Review, no. 75, Fall 2010, pp. 110-111; PDF)

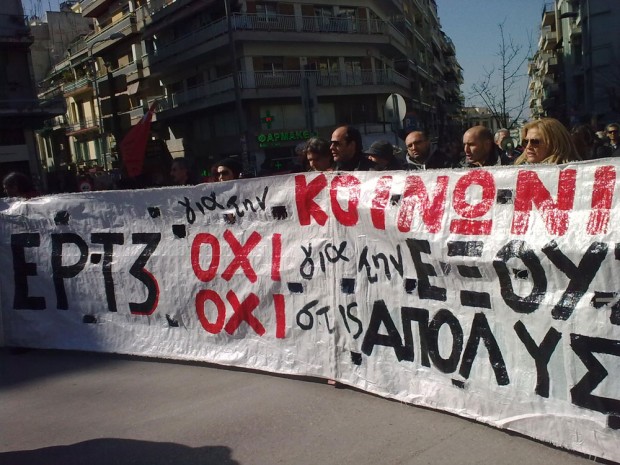

[UPDATE–March 22, 2013] The same slogan was used during a recent demonstration by workers of the media organization ERT3 in Thessaloniki (image retrieved from Asyntaxtos Typos: “ΜΜΕ για την κοινωνία και όχι για τα λαμόγια της κάθε εξουσίας…” February 21, 2013):

• • •

Previously: Robert Esposito

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication

- Tagged: communitas, community, crisis, economy, Esposito, Greece, koinonia, power