An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

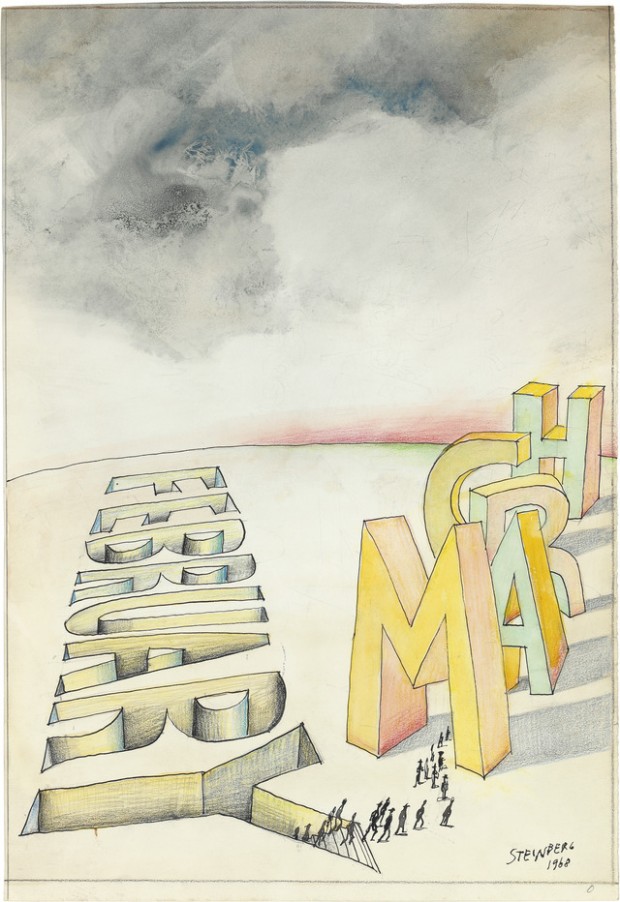

☛ Pace Gallery: “February to March” by Saul Steinberg, colored pencil, graphite, ink and watercolor on paper, 21-1/2″ x 14-3/4″ (54.6 cm x 37.5 cm), 1968. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation.

Although this illustration was created in 1968, a search through The New Yorker’s archive seems to indicate that it was first published in the edition of February 14, 2005 (p. 262). A black-and-white version is also available at The Cartoon Bank.

This drawing in particular is reminiscent of a similar one Steinberg created two years earlier which was used in March 1966. See here: “March to April” by Saul Steinberg, 1966.

One of the striking and original features of Saul Steinberg’s drawings resides in his ability to illustrate abstract although familiar concepts: passing time (below is another example), space, nation, imagination, consciousness, etc. This aspect is covered by Ian Frazier in the essay he wrote for the excellent book Steinberg at the New Yorker:

But while painters sought to divorce their art from visual representation, Steinberg turned in quite a different direction, to the demotic language of comics. Against the simple conceit of realist painting ―that visual facts about the world are adequate, in Rothko’s phrase, to “express the world”― the expansive vocabulary of comics provides visible forms for invisible phenomena: sound effect, thought and talk balloons, popping sweat-beads of emotion, stink lines, and outsize punctuation marks to signal relief and ecstasy and pain. Steinberg drew in the language of comics insofar as he portrayed things not as they appear but as the multisensory mind pictures them. But the subject he drew about ―memory, geometry, history, semantics, reason, weather, language itself― departed drastically from the typical thematic range of comics, and of New Yorker cartoons as they had existed before him.

“I am a writer who draws,” Steinberg half-explained, and in The New Yorker, his art indeed functioned less like the work of his fellow cartoonist than like the fiction of, say, John Cheever or J.D. Salinger: crystallizing the experience of thoughtful readers, he proposed vivid emblems for their daily habits of mind. Even in his most straightforward early cartoons, he was liable to pose intellectual puzzles about representation or address modern alienation (…) (Steinberg at the New Yorker by Joel Smith with an introduction by Ian Frazier, 240 pages, 363 illustrations, Harry N. Abrams, 2005, pp 30, 32; Amazon).

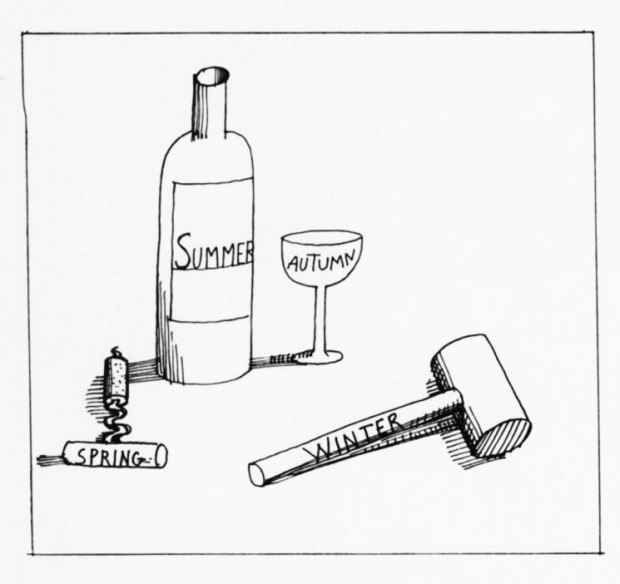

Below is another drawing representing the passing of time. This one does not address the transition between months but suggests instead the cycle of seasons. It’s part of “12 Variations” on this theme and is included in Steinberg at the New Yorker as well (pp. 176-177).

I first spotted “February to March” via This Isn’t Happiness.

• • •

Previously: “Santa Claus as Christmas Tree” by Saul Steinberg, c. 1949

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Illustration

- Tagged: February, march, months, Saul Steinberg, spring, time, winter