An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

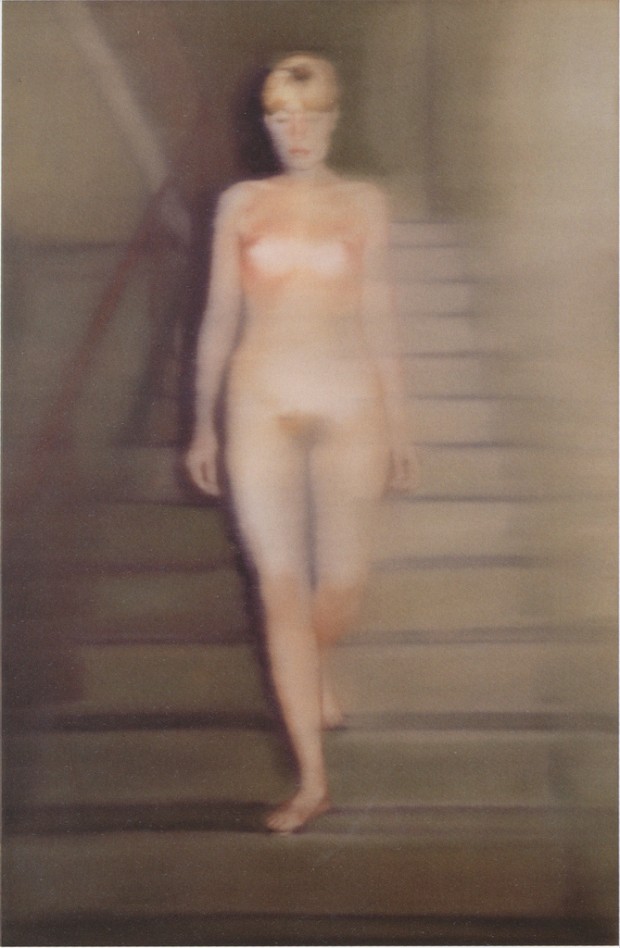

☛ Gerhard Richter: “Ema-Akt auf einer Treppe”, Ema (Nude on a Staircase), 1966, oil on canvas, 200 x 130 cm. Large format reproduction retrieved from Flickr.

“Ema” experienced some censorship problems lately, I’ll come to those after a few comments about the painting itself.

As it is the case with any kind of reproduction, the image above is only one of numerous variations one can find online. As a starting point for comparison, see the same image on Museum Ludwig website (the painting currently belongs to this museum’s collection). It’s also important to remember that “Ema” exist in two distinct art media: as an original oil painting and as a cibachrome photograph of roughly the same size, produced by Gerhard Richter in a limited edition of twelve plus one artist’s proof. One can see a large format reproduction of the cibachrom photograph on the Art Gallery of New South Wales (in Sydney, Australia) website. A large format reproduction is also available on WikiPainting, but the reproduction comes from the Art Gallery NSW (which owns, as stated above, a cibachrom photograph of the painting, not the painting itself).

The painting is a portrait of Gerhard Richter’s first wife, Ema, produced from a photograph he took of her. It’s also a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s painting “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2” (1912). A little bit of context is offered by the Art Gallery of New South Wales:

Richter began painting figuratively in a European variation on pop art in the 1960s. His subject matter was often derived from newspaper photographs and mimicked the blurred effect of a black-and-white photo taken from a moving car. They also suggested political surveillance images, an idea given greater force by Richter’s professional origins in Eastern Germany. Richter has maintained a continuing dialogue with photography; in his installation ‘Atlas’ at Dia Center for the Arts in New York in 1995–96 he exhibited over 4000 photo-graphs, along with newspaper and magazine clippings. Assembled since 1962, this collection of images is a source that parallels the development of subject matter in his art.

‘Ema’, made for the 1992 Biennale of Sydney, is a photograph of a painting that Richter produced in 1966, ‘Ema (nude on a staircase)’. The photograph is the same size as the original painting of Richter’s wife Ema, which inevitably recalls Duchamp’s famous ‘Nude descending a staircase’ of 1912. Yet compared to the machine-like movement of Duchamp’s figure, Richter’s is more sensual, even classical, with its frontal nudity and soft blurring. Richter’s painting was in turn based on a photograph he had taken of his wife. The interplay between the two media means that the large 1992 photograph appears painterly while the painting itself has the effect of a blurred photograph with light catching the body of the nude.

At Phillips de Pury & Company one can find more details about the relationship between the original oil painting and the limited edition of cibachrom photographs that were made from it, as explained by the artist himself:

In the photograph, I take even more focus out of the painted image, which is already a bit out of focus, and make the picture even smoother. I also subtract the materiality, the surface of the painting, and it becomes something different. (G. Richter, from H. Butin: “Gerhard Richter and the Reflection on Images” in Gerhard Richter Editions 1965-2004, Catalog Raisonne, Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004, pp. 55, 59)

In his book Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting (2002), Robert Storr provides a more thorough explanation of the relationship between Richter’s painting and the one produced by Duchamp several years earlier:

A year later, Richter painted Ema (Nude on a Staircase), a subtly tinted color portrait of his wife. The titles, of course, refer to Marcel Duchamp’s notorious iconoclast Nude Descending a Staircase of 1912. But the painting of Ema, with its lovely diffuse naturalism, may be taken as an act of counter-iconoclasm. Indeed, Richter seems never to have been wholly convinced of the radicality of Duchamp’s work in the first place. “A very beautiful painting, and utterly traditional,” he said, and in the strict technical sense of its being an old-fashioned easel painting executed in the old-fashioned way, he was correct. An inversion of the Readymade, in that it is based on a photograph Richter took for the purpose rather than a found image (it was the first time he had done so), it was the most classical pose the artist had yet painted despite its having been explicitly inspired by an anticlassical Cubist masterpiece. To the degree that it is a witty gesture of defiance directed toward the neo-Dada practices in favor among his peers, the work is an argumentative entry into the public discourse, but not the last part of that argument consists of the artist’s tender portrayal of his own private reality. It is not just the depiction of any nude descending a staircase, it is Ema. (Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, The Museum of Modern Art, 2002, p. 40)

• • •

There’s currently a major, ongoing exposition featuring Gerhard Richter at the Centre Pompidou, in Paris (from June 6 through September 24, 2012). On July 20, 2012, Centre Pompidou published a reproduction of “Ema” on its Facebook Page. The very same day, the image was taken down by Facebook, initially for probable violation of its Statement of Rights and Responsibilities policy which states:

You will not post content that: is hate speech, threatening, or pornographic; incites violence; or contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence.

The take down was a mistake and Facebook quickly restored the image and apologized for the inconvenience (the whole story was told by the blog Les notes de Véculture: see Part 1 and Part 2, in French). It’s not the first time such a mistake happens. Two years earlier, following a similar incident, Facebook issued to following statement:

“Our policy prohibits photos of actual nude people, not paintings or sculptures. We recognize that this policy might in some cases result in the removal of artistic works; however, it is designed to ensure Facebook remains a safe, secure and trusted environment for all users.” (Huffington Post: “When Is a Nude OK on Facebook?” by John Seed, May 24, 2010)

The extent to which this “security” policy is hard to apply was fully exposed recently when The New Yorker saw its Facebook Page censored over a cartoon depicting Adam and Eve (cartoon editor Robert Mankoff gave a hilarious account of the whole misadventure: “Nipplegate: Why the New Yorker Cartoon Department Is About to Be Banned from Facebook”, Sept. 10, 2012).

The fact is users everywhere now rely on apparatus which are willing (and able) to enforce their own codes of conduct. Those apparatus do decide what is acceptable and what is not and, furthermore, act upon those self-declared criteria. Which is to expect (and welcome to a certain extant) but also, as we see every day, problematic.

Google just recently added The Pirate Bay ―a popular file-sharing website notorious for making copyrighted content easily available online― to the list of search results it will blacklist in an effort, it is said, to slow down online copyright infringement (see TorrentFreak: “Google Adds Pirate Bay Domains to Censorship List”, Sept. 10, 2012). This problem –Internet corporations trying to enforce a code of conduct– is not new, but it’s likely to increase in importance in the coming years. Furthermore, those multinational corporations are far from being above reproach themselves. For example, although Google has agreed to sign a “code of conduct intended to protect online free speech and privacy in restrictive countries” ―known as the Global Network Initiative― Twitter and Facebook both declined to join in (The New York Times: “Sites Like Twitter Absent From Free Speech Pact” by Verne G. Kopytoff, March 6, 2011).

For a good introduction on some general aspects of this problem see the entry “Search Engines and Ethics” by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Art, Communication, Painting, Technology

- Tagged: censorship, ethic, Facebook, Gerhard Richter, nude, representation, woman