An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

Here, the concept of objective spirit turns into the principle of information. This steps between thoughts and things as a third value, between the pole of reflection and the pole of the thing, between spirit and matter. Intelligent machines -like all artifices that are culturally created- eventually also compel thought to recognize on a broader front the fact of the matter that here, quite obviously, “spirit” or reflection or thought is infused into matter and remains there ready to be re-found and further cultivated. Machines and artifices are thus real-existing negations of the conditions before the imprinting of the in-formatio into the medium. They are in this sense memories or reflections turned objective. In order to conceive of this, one needs an ontology that is at least bivalent as well as a trivalent logic, which is to say a cognitive toolkit capable of articulating that there are real-existing affirmed negations and negated affirmations, that there are nothings in a state of being, and beings in a state of nothingness. In the end, the statement, “there is information,” says nothing else. It is to make this statement possible and to consolidate it that Hegel and Heidegger engage in an intellectual battle of giants – a battle into which authors such as Günther, Deleuze, Derrida and Luhmann have entered with considerable effect. They all work to conquer the tertium datur.

☛ Die Domestikation des Seins. Für eine Verdeutlichung der Lichtung by Peter Sloterdijk, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 2000; trans. of the fourth chapter as “The Operable Man” by Joel Westerdale and Günter Sautter (slightly modified).

• • •

The excerpt quoted above comes from a translation of the fourth and final chapter of the essay. For a while this English translation was hosted both at the Goethe Institute website and at Peter Sloterdijk official website. Those links no longer work, but the text can be access using the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine here and here. There are slight differences between the French and English translations (in the English version, a part of a sentence is missing, a quote by Heidegger is shorten). At the time of writing, a complete English translation of the whole essay still doesn’t exist.

I don’t know if Die Domestikation des Seins was ever published as a standalone text before being included in the volume Nicht gerettet: Versuche nach Heidegger (Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 2001). Some online bibliographies seem to suggest it did, but I could not find trace of a standalone edition at Suhrkamp.

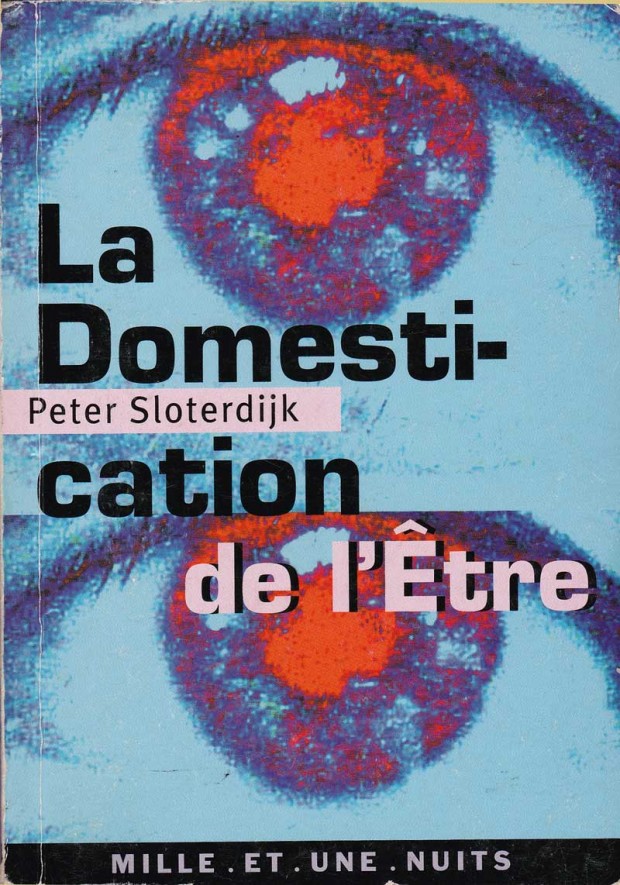

The essay was translated in French by Olivier Mannoni as La domestication de l’être and published by Mille et une nuits on September 2000. This edition –which front cover is reminiscent of the Star Gate sequence in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey– has been out of print for many years. In November of 2010, the same French translation was re-published in a volume that also includes Règles pour le parc humain (Paris: Fayard/Mille et une nuits). For more information about the French translation of Regeln für den Menschenpark, see previously here. It is worth keeping in mind the Regeln… essay was produced before Die Domestikation….

A first draft of the French translation by Olivier Mannoni was presented by Peter Sloterdijk at the symposium “Cloner or not cloner” held by the Pompidou Center on March 28 to 30, 2000. Sloterdijk presentation was then titled “Clairière turbulente. Pour une réminiscence de l’anthropologie philosophique”. A partial audio recording of his participation is available online, both at the Pompidou Center website and on YouTube). The 55-min recording ends abruptly in the midst of what is equivalent to the third chapter of La domestication de l’être, just before the presentation of the four anthropogenic mechanisms (page 45 in the first Mille et une nuit edition). Those 55 minutes still represent half of Sloterdijk’s essay.

At his blog Progressive Geography, Stuart Elden shares some useful information about the works by Peter Sloterdijk that are currently available in English, while also proposing reading suggestions for those less familiar with his prolific production: see “Where to start with reading Peter Sloterdijk?”. Elden also links to Sean Sturm’s bibliography of texts by Sloterdijk already translated into English: “Peter Sloterdijk in English”. I have linked to Sturm’s blog back in 2011, but the bibliography is being regularly updated: the last update was made in July 2013.

Like many others, I first came in contact with the work of Peter Sloterdijk in 2000, through the French translation of both Regeln für den Menschenpark and Die Domestikation des Seins.

Previous works by Sloterdijk had already received international acclaimed. His Critique of Cynical Reason (Kritik der zynischen Vernunft) was hailed both by Michel Foucault and Jürgen Habermas when it first appeared in 1983. However, one could safely say that the major controversy surrounding the publication Regeln für den Menschenpark in 1999 introduced Sloterdijk to a much broader audience, outside the national circle of German philosophy. At its center, this controversy was concerned with Sloterdijk’s critique of humanism formulated through the theme of “domestikation”. This theme would be further developed in the essay Die Domestikation des Seins.

Therein lies the critical importance of those two short, but dense essays. Controversy aside, I believe they also provide an excellent introduction to Sloterdijk’s major ideas, especially in regard to media theory (Regeln), and to his theory of space (Die Domestikation).

For a good introduction, in French, to the the Habermas-Sloterdijk-controversy, see Alexandre Dupeyrix: “La controverse entre Jürgen Habermas et Peter Sloterdijk” (2005). Sloterdijk commented it in an “Afterword” he wrote for the French edition of Regeln für den Menschenpark (this afterword is not included in the English translation of “Rules for the Human Zoo”). He also talked about it during an interview with Éric Alliez published in the very first issue of Multitude, in March 2000: “Vivre chaud et penser froid”.

• • •

Previously:

- Posthumanism: Sloterdijk and the problem of political synthesis

- The end of the belief in education (Peter Sloterdijk, 1983)

- Peter Sloterdijk: “We share the separator” (2005)

- Christoph Gielen’s Photographs meet Peter Sloterdijk’s “Poetic of Space”

- Peter Sloterdijk and the specificities of modern terrorism

• • •

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Technology

- Tagged: dialectic, Heidegger, humanism, machine, media, Sloterdijk