An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

In an age of information overload, information discovery — the service of bringing to the public’s attention that which is interesting, meaningful, important, and otherwise worthy of our time and thought — is a form of creative and intellectual labor, and one of increasing importance and urgency. A form of authorship, if you will. Yet we don’t have a standardized system for honoring discovery the way we honor other forms of authorship and other modalities of creative and intellectual investment, from literary citations to Creative Commons image rights.

☛ Brain Pickings: “Introducing The Curator’s Code: A Standard for Honoring Attribution of Discovery Across the Web” by Maria Popova, March 9, 2012.

As a follow-up, I added a small update at the end of this post one year later, in march 2013.

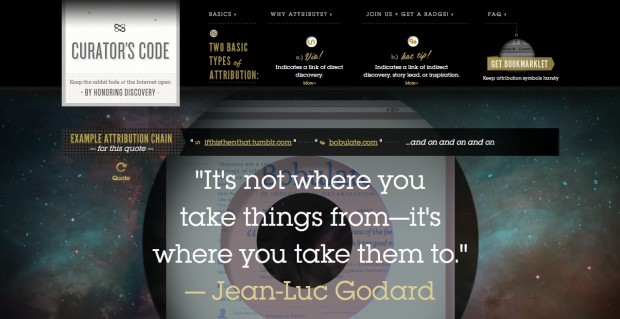

On March 9, 2012, Maria Popova of Brain Pickings unveiled a new project: the Curator’s Code.

There were immediate responses to this initiative. Some of those were simply stating the details from the project, others were less enthusiastic and point out some problems about it while some were explicitly hostile (see the very end of this entry for a small roundup of those reactions).

I think any kind of intelligent discussion or debate about proper source attribution methods in general should be welcome at the present time. The stakes are much more important than simply acknowledging a “hat tip” on Twitter, although they are likely related. They are also quite complex. From a very broad point of view, they encompass our relationship to authority (auctoritas is the same word that gives us both “authority” and “authorship”1), the way we handle the past (the relation between news and archives, immediate attention and memory), the increasing quantity of information we’re exposed to on a daily basis, genealogy and our understanding of the idea of “origin” (and therefor of “original”) in a world where “everything is a remix”2, where the author is dead3 or maybe not4.

From a more pragmatic perspective, the problems associated with source attribution are just as ubiquitous. They concern bloggers as well as academics, Tumblr as well as Google and Pinterest5, classical writers from two thousand years ago to young and upcoming designers. One may be studying in college or simply buying a bag covered with a quote from Che Guevara, posting photos on Flickr or working on a documentary and still face a problem of source attribution. Some may not care, but then others are there to care for them (either cordially6 or by means of cease-and-desist letters). It has to do with copyrights and copylefts, with fact checking and plagiarism, with fair use and public domain, with fame and money or sometimes more simply with personal hubris and intellectual integrity.

Although I’m also concerned about attribution, I won’t be “joining the public pledge” of the Curator’s Code nor will I, consequently, use unicode characters when it comes to “indicate a link of indirect discovery”. Like others, I have some problems about this project: they are listed below. As it is the case with many projects of this sort ―projects that rely on the diffusion of a new standard― time will unmistakably tell if they are able to reach a critical mass and sustain themselves, or not (It did not: see the end of this post for an update posted one year later, on March 2013). I have my doubts, but they are not likely to influence this outcome.

What is this “Curator’s Code”? It is supposed to be an initiative to promote a specific kind of attribution when doing content aggregation. It means that if one is publishing on the Internet and, in doing so, is using works from others, one is “encouraged” to give “proper” attribution. There’re three important things to note here:

- The Curator’s Code is not directly concerned with proper attribution of original authorship since this aspect is considered ―from the project’s point of view― to be under control:

[…] we have systems in place for literary citation, image attribution, and scientific reference […]

- Instead, the Curator’s Code proposes to use two unicode characters to indicate and differentiate between two different kinds of attribution: “link of direct discovery” or “link of indirect discovery”. I’ll come back to those in a moment. It’s important to understand that it does not impose the use of those unicode characters. The “Curator’s Code” website states:

This is not an effort to police the internet from a place of top-down authority, it’s an effort to encourage respect and kindness among the community. […]

If you’re having technical difficulties, or are confused by them, or just plain don’t like them, you can and should just use the standard “via” and “HT” options for direct and indirect attribution of discovery, respectively. The goal here is not to mandate how to attribute, but to encourage to attribute.

- Nonetheless, the Curator’s Code website offers a bookmarklet designed to facilitate the use of the two unicode characters proposed to indicate direct or indirect sources of “discovery”. The bookmarklet automatically hotlink those two characters to the Curator’s Code website. According to the website, this is done

(…) to allow the ethos of attribution to spread as curious readers click the symbol to find out what it stands for.

I see three problems associated with the aspects listed above. The first has to do with the way the Curator’s Code deals with proper attribution of original authorship (it doesn’t). The second has to do with the idea of attributing authorship to individuals who “discover” pre-existing material and write about it online. The third concerns the technicalities on which the project relies (at least in part). I close with a final remark about the quote attributed to Godard and prominently featured on the Curator’s Code website (see the screenshot above).

[UPDATE-August 30, 2012] The Curator’s Code website was significantly updated on April 2012. The update partially addresses three of the problems I listed above. 1) The quote attributed to Godard and, as a matter of fact, all the quotes by various authors used on the original version of the site are now hidden behind a new text panel titled “New to The Curator’s Code?”. 2) The problem of proper attribution of original authorship is now briefly acknowledged under the “Attribution 101” section of this new text panel. It’s the very first point: “Creators come first”. 3) Some technical aspects associated with the use of Unicodes characters are also discussed in the second point of the section “Attribution 101”: “Use the Unicodes–or don’t”. For archiving purpose, I’ve included a screenshot of the new text panel below.

• Proper attribution of original authorship

Authorship attribution is still an enormous problem both online and offline. College and universities face plagiarism on a regular basis while on the Internet smart quotes by Albert Einstein are endlessly reblogged without any indications whatsoever pertaining to their source of origin (where does the quote come from? When was it published or said? What was the general context from which it was extracted?). Even scholars are still struggling to find adequate attribution systems7.

I think source attribution should first be concerned with creator’s authorship (of a given work), then maybe with other kinds of attribution (via, “hat tip”, “indirect discovery” etc.). Or to put it another way: when I find a quote or an image online (or offline for that matter) I’m more interested in knowing who created it in the first place than learning about who brought it to my attention (this Tumblr blog or this Twitter user). For example, it doesn’t make much sense to deal with a direct or indirect “link of discovery” when the item “discovered” (or reblogged) remains inadequately referenced.

Back in September 2010, Tumblr’s staff announced they were “fixing content attribution (once and for all)”. This statement was quite dubious in its hyperbolic tone (something in the line of those “best movie ever!” claims). Back then, they explained:

But this feature has an even bigger win: When creating a post, you can now attribute its content (eg. a pull quote or image) to a source outside of Tumblr. That source gets clearly attributed everywhere that post is reblogged on Tumblr.[…] The bookmarklet will automatically set the source, confirming that the current page is in fact the content’s origin.

This may be a slight improvement, but in no way does it fix source attribution “once and for all”. If a user is surfing ffffound.com and decide the page he’s surfing is the content’s origin, the attribution will likely be erroneous. Two years later, the problem remains. For example, according to this Tumblr blog, the source for a quote by Godard is this other Tumblr blog. And no, it’s not Godard’s personal Tumblr blog. Source attribution, especially online, is not fixed.

I must stress that it’s not in my intention to be overly critical of the individuals who sometimes hastily reblog stuff without inquiring about the content’s origins. I’ve discovered a lot of interesting artists through websites such as ffffound.com or This Isn’t Happiness. When I’m really interested in a photo or an illustration and credit is missing ―as it is often the case―, I’ll take the time to try to track down information about the original creator. Reblogging ―with or without adequate source attribution― is an important function in that it allows for content to circulate and recirculate, to be discovered for the first time and rediscovered again. That being said, I still strongly believe that it’s preferable to give proper credit where credit is due. But I guess, as it was once suggested to me, that source attribution isn’t everyone’s cup of tea8.

As I said earlier, source attribution online is also a matter of context and personal dispositions. John Grubber is the author of the technology weblog Daring Fireball. When it comes to “attribution and credit” regarding online publishing, he has clear principles (see for example “On Attribution and Credit”, July 1, 2011). But when he’s quoting a book, he’s not as concerned with providing extensive attribution details. He seems okay with simpler attribution (see his “Quote of the Day” for November 28, 2011). Similarly, a scholarly article won’t use the same source attribution system as The New York Times or The New Yorker. They simply don’t have the same purpose. A single standard for source attribution could not possibly fit the need for the wide variety of publishing practices we are witnessing today.

So proper attribution of original authorship still needs to be openly discussed both offline and online. It simply isn’t something that anyone could possibly take for granted.

• Information discovery as a form of authorship

An important part of the Curator’s Code project comes from the idea that today “information discovery” is or should be considered “[a] form of authorship” (see the quote at the very top of this entry). Let’s take an example. The Curator’s Code’s website displays a quote allegedly attributed to Jean-Luc Godard. Let’s say I first found out about the quote through this website and now I want to reblog it or to write about it online. In this situation, the Curator’s Code encourages me to acknowledge the website for the discovery. The individual running the website could even be considered as the online “author” of this discovery (not only for having “discovered” it ―if that makes sense― but also for having “amplified” it, to use Popova’s own terminology).

I personally feel it’s common courtesy to acknowledge an intermediate source (or “via source” or “link of discovery”) when it provides me with valuable content in an informative way. I’m doing it every now and then by using readable words arranged in a sentence: “I first spotted this via The Atlantic”, for example. But I don’t feel obligated to do it the same way each time. It varies on a case by case basis. If an image is reblogged all over the place without any source attribution, I’m not likely to remember where I first saw it nor to acknowledge anyone in particular for putting it on the Internet (unless I can track down this user). Instead, I’ll do some research and give proper source attribution to the image itself without pointing to a particular “via” source.

In the publishing business, when someone rearranges, introduces, presents preexisting content in a new way, he or she is called an “editor”. There’s no doubt the editor is the author of the original content he or she created (a preface or introduction, for example). However, I never saw any case where the editor claims to be the actual “author” of the preexisting material he or she “edited”.

• Technological aspects

Finally there’s the problem of the means: the technological aspects. Hotlinking the unicode character to the Curator’s website maybe an interesting way to help the diffusion of its proposed standards. However, it’s likely to become a problem overtime. Will this website be up and running in ten years? Or will the links be broken and the purpose defeated: a user clicking the strange unicode characters to find what they are about may one day face a 404 page. The serious design of an attribution standard shouldn’t rely on rapidly changing technology. I believe that’s the reason the Modern Language Association didn’t include a URL when they propose their new standard for citing a Tweet (see “How do I cite a tweet?”). URLs are likely to break over time and unless they are descriptive URLs (which is not the case for Twitter) they are unreadable by humans. In the end, I believe it’s still safer to use readable words for “link discovery” attribution (when it applies): “I first found this at” or “I became aware of that via”, for example.

• Final remark: An unsourced quote

I’d like to offer one final remark about a small but somehow relevant detail on the Curator’s Code website. The quote by Godard shown in the screen capture I used earlier tells of another problem: it’s unsourced. Even if one goes back through the “whimsical rabbit hole of discovery” (as the Internet is described on the website), following one via link to the other, one will not find (at the present moment) any information pointing to the actual source of Godard’s quote: when did he say or write that sentence? Was it in English or in French? What was the context in which he made such a statement? We don’t know. All we know for sure is that filmmaker Jim Jarmush wrote this quote and attributed it to Jean-Luc Godard without further information in his essay “Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Rules” published over at MovieMaker Magazine on January 22, 2004.

I’m certainly not suggesting that Jarmush may be lying or even mistaken. All I’d like to have is a little bit more information about Jean-Luc Godard’s quote, a little more context9. Which I can’t find. I would in fact like to acknowledge Jean-Luc Godard himself ―give him proper attribution― for having said or written down this idea.

It could be argued that this lack of original source is precisely addressed by the quote itself: “It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.” But if the original source doesn’t matter, why still use quotation marks as well as the author’s name? Among other things, possibly because in this case it provides authority and therefore power10 (cycling through the quotes on the website, it looks like the Curator’s Code ideas are backed up by famous author: Charles Eames, Chuck Palahniuk, Ezra Pound and even Carl Jung). The practice of quoting an author to profit from his authority without really caring about where the quote comes from or even if the quote is accurate and authentic is not uncommon, nor is it systematically reprehensible. However, to see it in use on a website claiming “the goal here is to attribute ethically” is puzzling, to say the least.

[UPDATE–March 17, 2013]. On March 9, 2013, Maria Popova didn’t mention the first anniversary of her Curator’s Code on her blog Brain Pickings nor on her Twitter feed. I tried to reach both her and David Carr (who wrote a piece about the Curator’s Code at the time for The New York Times) by emails and through Twitter but they didn’t reply back. An online search showed that the anniversary was in fact largely ignore. I found basically no mention of it between March 9 and March 17 except for one tweet by Joshua Topolsky (“Happy anniversary to the Curator’s Code #SXSW”, 10:11 PM, 11 Mar 13) and a small comment in the Editors Weblog of the World Association of Newspaper and News Publishers to the effect that it had failed to caught on:

Additionally, BrainPicking’s Maria Popova developed the Curator’s Code, a shorthand for citations that recognizes information taken directly from other sources and additional commentary on other websites. Considering we haven’t heard much from the Council since its creation last spring and you don’t see Curator’s Code symbols on many blog posts, clearly neither of the proposed options have caught on. (see “Thayer, Williams plagiarism scandals highlight undefined standards for online attribution” by Kira Witkin, March 11, 2013)

• • •

• Link roundup

Here’s a small roundup of various reactions published online regarding the Curator’s Code project:

- Of course, one should first visit the Curator’s Code official website and read Maria Popova’s unveiling announcement over at Brain Pickings. For more about her opinion on authorship and curation, see the piece she wrote for Nieman Journalism Lab: “In a new world of informational abundance, content curation is a new kind of authorship” by Maria Popova, June 10, 2011.

- The Atlantic: “The Curator’s Guide to the Galaxy” by Megan Garber, March 11, 2012.

- From The New York Times: “A Code of Conduct for Content Aggregators” by David Carr, March 11, 2012. Also, search the comments for those shared by Tim McCormick.

- Matt Langer: “Stop Calling it Curation”, March 12, 2012.

- ReadWriteWeb: “Down the Rabbit Hole with Hyperlinks in Hand: On the “Curator’s Code”” by Scott M. Fulton, III, March 12, 2012.

- Gawker: “We Don’t Need No Stinking Seal of Approval from the Blog Police” by Hamilton Nolan, March 12, 2012. To be fair, that’s more a reaction to David Carr’s column. It doesn’t specifically address the Curator’s Code project.

- The Brooks Review: “Blogging About Blogging” by Ben Brooks, March 12, 2012.

- Marco.org: “I’m not a “curator”” by Marco Arment, March 12, 2012.

- DesignNotes: “Curator’s Code ― No Thanks” by Michael Surtees, March 13, 2012.

- .net magazine: “Behind the Curator’s Code” by Craig Grannell, March 19, 2012.

- [UPDATE-April 7, 2012] At Enthusiasms, Simen makes a humorous but compelling argument about the use of the concept of “curation” when it comes to blogging: see “John Blogkowski, Curator of Hyperlinks, Dies at 81” (published online on April 6, 2012).

• • •

1. For a discussion about the etymology of the word “author” see in particular “Latin Etymologies” by J.B. Greenough (Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. 4, 1893, pp. 143-149; academic subscription may be required) and Emile Benveniste, Indo-European Language and Society, book 5, chapter 6: “The Censor and Auctoritas”, tr. by Elizabeth Palmer, University of Miami Press, [1969]1973; online edition revised and updated by Jeremy Lin, Jacqueline Lewandowski, and Vergil Parson. In his book, Benveniste explicitly address the problem of knowing if the verb augeo means “to increase” the act of someone else (in line maybe with Popova’s “amplifying” understanding of authorship) or if it rather refers to “the act of producing from one’s own breast”. It is Benveniste’s opinion that only the latter interpretation is valid. See footnote 9 for more.↩︎︎

2. Watch Kirby Ferguson’s four-part video series “Everything is a Remix”. Especially Part 4:

Our system of law doesn’t acknowledge the derivative nature of creativity. Instead, ideas are regarded as property, as unique and original lots with distinct boundaries. But ideas aren’t so tidy. They’re layered, they’re interwoven, they’re tangled. And when the system conflicts with the reality… the system starts to fail.↩︎︎

3. See Roland Barthes “La mort de l’Auteur” in Le bruissement de la langue, Paris:Seuil, [1968]1984, pp. 61-67; translated by Richard Howard as “The Death of the Author” in Aspen, no. 5-6, 1967. ↩︎︎

4. See Michel Foucault “Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur” in Bulletin de la Société française de philosophie, 63e année, no. 3, juillet-septembre 1969, pp. 73-104; translated by Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon as “What is an Author?” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 124-127. For a more general introduction to the concept of “author” see Antoine Compagnon’s online course (in French) “Théorie de la littérature: Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur?” hosted by Fabula.org. Also available in PDF format. Compagnon also wrote an important book about the concept of quotation: La seconde main ou le travail de la citation, Paris: Seuil, 1979 (Google Books without preview, Amazon.com) As of now I believe it hasn’t been translated to English. For an English review, see Comparative Literature vol. 34, no. 1 (Winter, 1982), pp. 70-73 (academic subscription may be required)↩︎︎.

5. For Tumblr see: “Fixing Content Attribution (Once and For All)” September 3, 2010. I discuss this initiative later in the post. For Google see: “Credit where credit is due” by Eric Weigle and Abe Epton, Nov. 16, 2010. Also for Google, an article from Inside Higher Ed pointing to problems with Google Books’s metadata: “Catalog of Errors?” by Matthew Reisz, December 8, 2011. Pinterest has a “Pin Etiquette” that clearly states:

Pins are the most useful when they have links back to the original source. If you notice that a pin is not sourced correctly, leave a comment so the original pinner can update the source. Finding the original source is always preferable to a secondary source such as Google Image Search or a blog entry.

Are those guidelines or suggestions followed by Pinterest users? Randomly browsing through various Pinterest accounts suggests that although “sources” are sometimes included with the item “pinned”, they rarely point back to an “original source”.↩︎︎

6. Like designer Christoph Niemann did a couple of days ago when he very politely asked the Tumblr blog I Love Chart:

@ilovecharts hey jason, thanks for tweeting my “odds of march” chart. can you include a credit line/link etc though? thanks! christoph

The nice folks at I Love Charts were glad (and prompt) to comply (see their post: “The Odds of March” published on March 14, 2012). Apparently, the picture and the title of their post was already linked to the original source (in this case to Christoph Niemann’s original post at The New York Times). The attribution however looked inadequate in Niemann’s eyes. It shows how the problem is not simply about attribution in general: it is more precisely about the ways to provide proper and adequate source attribution. Reference for Niemann’s tweet: Niemann, Christoph (@abstractsunday). “@ilovecharts hey jason, thanks for tweeting my “odds of march” chart. can you include a credit line/link etc though? thanks! christoph” 14 March, 2012, 7:31 AM. Tweet. ↩︎︎

7.See for example The Atlantic: “Scholars: Yes, We Need Better Attribution Systems (but No, We Don’t Know How to Make Them, Either)” by Megan Garber, March 15, 2012. See also this recent scholarly article from the Journal of Management Inquiry: “The Internet is Not Necessarily the Scholar’s Friend” by Luigi Proserpio (January 2012, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 119-123; academic subscription may be required). ↩︎︎

8. I previously wrote about such a case: see Cars 2, Transformers: summer jokes about Intelligent Design. ↩︎︎

9. Ironically, Maria Popova proposed a quote by Joanne McNeil about the importance of contextualisation in a follow-up post published on March 16 (see “What We Talk About When We Talk About “Curation””). The quote reads:

A good curator is thinking not just about acquisition and selection, but also contextualizing.

I wrote “ironcally” because Popova did not provide any context about the origin of this quote. The reader must guess it actually comes from the video featured in the same post (see below for more details) and then do some research to find out who’s Joanne McNeil. She’s actually a science and technology writer working and living in Brooklyn. She also happens to be the editor of Rhizome.org. For more see her official website. Back on September 30, 2010 Joanne McNeil recorded a podcast about curation with Jerry Brito for his website Surprisingly Free (see “Joanne McNeil on online introversion and curation” posted online on October 4, 2010). The part about curation starts at 16’06”. McNeil’s understanding of the word “curator” is actually much more precise than Popova’s personal interpretation of it. For McNeil curation is to be understood from the perspective of art. An art curator’s has two main functions. First, the curator discovers and exposes the context from which an item comes. Second, the curator helps to preserve both the item and the surrounding story which gives it its meaning. So, as McNeil explains, it’s not simply about selecting, editing or collecting stuff: blogging and curation are two different things. Maria Popova has a broader and looser view about curation, a view that’s nonetheless increasingly shared among social media experts and users (as McNeil points out). This broader view is exactly what allows Percolate –a new publishing platform specializing in social media marketing– to call its services “curation” (or curation enabling: “Percolate turns brands into curators”).

Percolate happens to be the producer of the video from which McNeil’s quote was extracted: “What is Curation?” (created with the help of m ss ng p eces, a Brooklyn-based creative company, and uploaded on Vimeo on March 14, 2012). Percolate was founded in 2011 by Noah Brier and James Gross and claims “to help brands create content at social scale” by

consum[ing] the world for a brand: Bubbling up the most interesting stories and making it easy to comment on those stories and push them out to a brand’s .COM, Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, or even ad units.

(See the About section of their official website). As I see it, Percolate is somewhere in between a marketing firm and a public relation firm. The way Percolate sees “curation” is very much in sync with Maria Popova’s own idea. From their perspective too, content aggregation (and filtering) is a form of creation: it’s selective content aggregation done by humans (here called “curators”) instead of algorithms.

The number one question brands ask today is ‘how do we create content for the social web?’ Our answer is curation. Percolate bubbles up interesting content from around the web and presents it back to a brand editor to add a comment and publish back out to social channels and websites.

Percolate’s “bubbling” sounds a lot like Maria Popova’s “amplifying”: they both see curation as a process of augmentation. However, what Percolate amplifies is essentially money. Historically, the individual capable of amplifying or augmenting money was called an auctioneer: he’s the one with the power to increase the monetary value of an item. Although “auctioneer” and “author” share an etymological ancestor through the Latin “auctoritas” their respective evolution brought them to designate very distinctive functions. For more see footnote 1, especially the work by J.B. Greenough. ↩︎︎

10. Here, I’m cutting corners: the relation between authority and power is problematic and has been (still is) subject of much debate. See for example State of Exception by Giorgio Agamben, especially chapter six: “Auctoritas and Potestas” (tr. by Kevin Attell, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, [2003]2005, pp. 74-88). See for example on page 75:

In 1968, in a study of the idea of authority published in a Festgabe for Schmitt’s eightieth year, a Spanish scholar, Jesus Fueyo, noted that the modern confusion of auctoritas and potestas (“two concepts that express the originary sense through which the Roman people conceived their communal life” [Fueyo 1968, 213]) and their convergence in the concept of sovereignty “was the cause of the philosophical inconsistency in the modern theory of the state”; and he immediately added that this confusion “is not only academic, but is closely bound up with the real process that has led to the formation of the political order of modernity” (213).

Also relevant for the discussion here is the following passage by Agamben, on page 76:

The term derives from the verb augeo: the auctor is is qui auget, the person who augments, increases, or perfects the act–or the legal situation–of someone else. In the section of his Indo-European Language and Society dedicated to law, Benveniste sought to show that originally the verb augeo (which, in the Indo-European area, is significantly related to terms that express force) “denotes not the increase in something which already exists but the act of producing from one’s own breast; a creative act” (Benveniste 1969, 2: 148/422). In truth, the two meanings are not contradictory at all in classical law. Indeed, the Greco-Roman world does not know creation ex nihilo; rather, every act of creation always involves something else–formless matter or incomplete being–that must be perfected or made to grow. Every creation is always a cocreation, just as every author is always a coauthor.

It could be tempting to apply this interpretation to the problems at hand here. Two things should prevent us from doing so too quickly. Agamben’s analysis is concerned with 1) ancient Greco-Roman world; 2) the genealogy of classical law. Everything may very well in fact be a remix, but from a modern legal as well as bibliographical perspective, only one author wrote State of Exception: Giorgio Agamben.↩︎︎

Agamben had already examined the meaning of the term “author” at length in §4.6 of Remnants of Auschwitz ([1998] 1999).

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Communication, Technology

- Tagged: aggregation, attribution, author, authority, authorship, credit, curation, digital curation, information, Internet, power, reblogging, source attribution