An iconographic and text archive related to communication, technology and art.

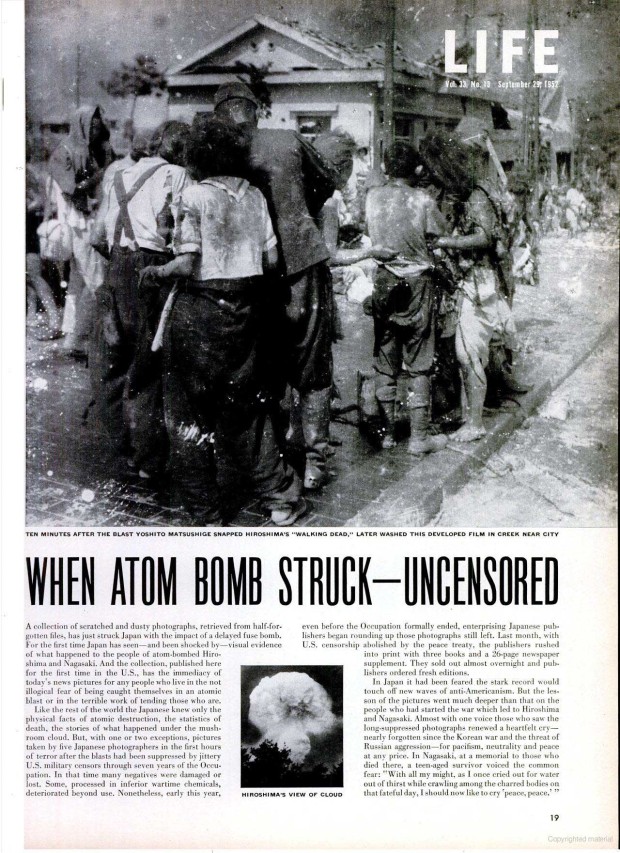

☛ LIFE magazine: from the article “When Atom Bomb Struck–Uncensored”, Sept. 29, 1952, p. 19. “Ten minutes after the blast Yoshito Matsushige snapped Hiroshima’s “Walking Dead,” later washed this developed film in a creek near city”.

Yoshito Matsushige was a 32 year old cameraman for the Chugoku Newspaper at that time. He was at his home in Midori-cho, 2.7kilometers from the hypocenter when the A-bomb was dropped. He walked around the city right after the bombing and took five photographs which have become important historical documents. (“Voice of Hibakusha”)

Yoshito Matsushige was a “hibakusha”, a bomb-affected victim (he died in 2005: read his obituary at The Japan Times). He witnessed the blast of the atomic bomb in the morning of August 6, 1945. He is one of the few to have produce a photographic record from the ground level of the mushroom cloud that formed over Hiroshima that day. The five photos he took can been seen at Max McCoy website.

Yoshito Matsushige shared his testimony in the documentary film Hiroshima Witness produced in 1986 by Hiroshima Peace Cultural Center and NHK. Here’s an excerpt where he explained how hard it was to take the picture depicted above, which was produced 40 minutes after the blast:

Most of the victims who had gathered there were junior high school girls from the Hiroshima Girls Business School and the Hiroshima Junior High School No.1. they had been mobilized to evacuate buildings and they were outside when the bomb fell. Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered with blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs. Some of the children even have burns on the soles of their feet. They’d lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire. When I saw this, I thought I would take a picture and I picked up my camera. But I couldn’t push the shutter because the sight was so pathetic. Even though I too was a victim of the same bomb, I only had minor injuries from glass fragments, whereas these people were dying. It was such a cruel sight that I couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter. Perhaps I hesitated there for about 20 minutes, but I finally summoned up the courage to take one picture. Then, I moved 4 or 5 meters forward to take the second picture. Even today, I clearly remember how the view finder was clouded over with my tears. I felt that everyone was looking at me and thinking angrily, “He’s taking our picture and will bring us no help at all.” Still, I had to press the shutter, so I harden my heart and finally I took the second shot. Those people must have thought me duly cold-hearted. […]

I walked for close to three hours. But I couldn’t take even one picture of that central area. There were other cameramen in the army shipping group and also at the newspaper as well. But the fact that not a single one of them was able to take pictures seems to indicate just how brutal the bombing actually was. I don’t pride myself on it, but it’s a small consolation that I was able to take at least five pictures. (“Testimony of Yoshito Matsushige”)

The smaller image reproduced on the page of LIFE magazine was taken by Seizo Yamada a couple of minutes after the explosion. More information is available at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, along with additional photos.

• • •

The difficulties Yoshito Matsushige met in his attempt to take pictures of the devastation echo to a certain extent one of the central themes in Günther Anders’s work. In the book Hiroshima ist überall, which has yet to be translated into English, he explained how he came to think about this difficulty –which he would later named “the Promethean gap” (Das Prometheische Gefälle)– as the central problem of our time (see previously here: “Commandments in the Atomic Age” by Günther Anders, 1957). Similar ideas were developed in another essay titled “Über die Bombe und die Wurzeln unserer Apokalypse Blindheit”. A partial English translation of this essay appeared in Dissent magazine, in 1956:

The “action” of unleashing the bomb is not merely irresponsible in the ordinary sense of the term: irresponsibility still falls within the realm of the morally discussible, while here we are confronted with something for which no one can even be held accountable. The consequences of this “action” are so great that the agent cannot possibly grasp them before, during, or after his action. Moreover, in this case there can be no goal, no positive value that can even approximately equal the magnitude of the means used to achieve it.

This incommensurability of cause and effect or means and end is not in the least likely to prevent the action; on the contrary, it facilitates the action. To murder an individual is far more difficult than to throw a bomb that kills countless individuals; and we would be willing to shake hands with the perpetrator of the second rather than of the first crime. Offenses that transcend our imagination by virtue of their monstrosity are committed more readily, for the inhibition normally present when the consequences of a projected action are more or less calculable are no longer operative. The Biblical “They know not what they do” here assumes a new, unexpectedly terrifying meaning: the very monstrousness of the deed makes possible a new, truly infernal innocence. (“Reflections On The H Bomb”, Dissent, vol. 3, no. 2, Spring 1956, p. 151; PDF).

• • •

Previously:

- By Philippe Theophanidis

- on

- ― Published in Uncategorized

- Tagged: atomic, death, Günther Anders, Hiroshima, incommensurability, nuclear, representation